The year 1921 was one of the worst years in the history of the American automobile business. Many companies folded in a brief but severe post-war recession as prices dropped and car inventories piled up. Walter P. Chrysler, after a stellar career at General Motors’ Buick division from 1911 to 1919, had tried to turn around major industry player Willys–Overland, for which he was paid one million dollars a year (equivalent to $15 million in 2020 dollars). But his management style did not jibe with that of wheeler-dealer founder John North Willys.

So, in 1921, Chrysler took over the deeply troubled and indebted Maxwell Motor Company, another former significant competitor. His friends thought him insane, as Maxwell had declined from the fourth largest make seven years earlier to tenth and was producing only sixteen thousand cars a year, compared to Henry Ford’s nine hundred thousand Model Ts. It was clear to most industry observers that the industry would be dominated by Ford, and perhaps General Motors, with its diverse product line-up including Buick, Cadillac, Oldsmobile, and Chevrolet.

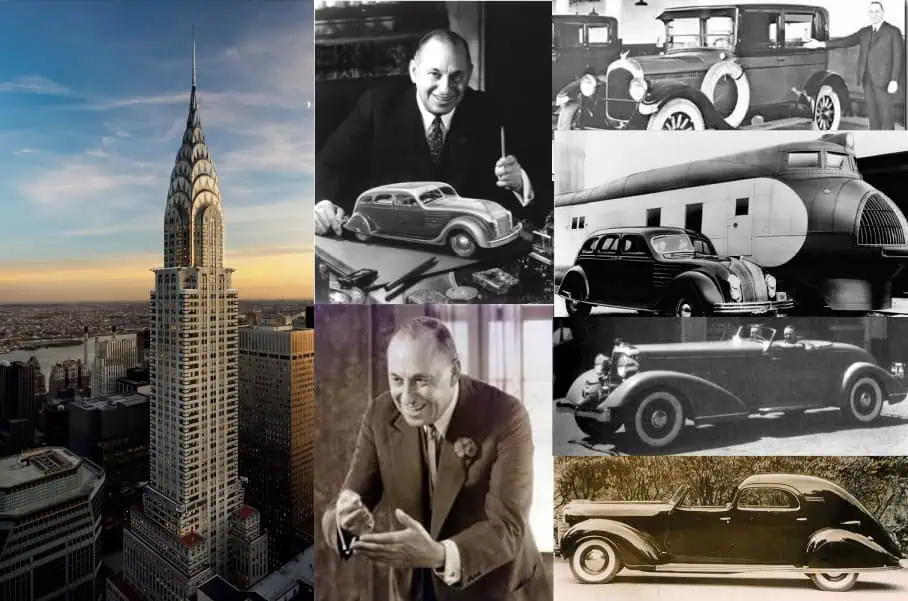

Yet Walter Chrysler’s drive, intelligence, and camaraderie with his men allowed his company, renamed the Chrysler Corporation in 1925, to grow and prosper. The company’s reputation was built on engineering innovation. By 1937, the company was making one million cars a year, and had surpassed Ford to become the second biggest American automaker after GM. Chrysler retained this second-place position for roughly the next fourteen years and continues today as a major player in the global auto industry.

Unlike the inventive but eccentric Henry Ford and GM’s brilliant leader and organizational pioneer Alfred Sloan, Walter Chrysler was above all else a working man. Every friend he made throughout his diverse life was a friend for life, no matter their social status, wealth, race, or job. He started his career repairing and servicing giant steam locomotives on the plains of Kansas. He ended his career as one of the richest Americans, planning and building the beautiful art deco Chrysler Building as an investment for his four children. Here is the story of this amazing, unsung industrial giant.

Beginnings: Ellis, Kansas

Walter Percy Chrysler was born April 2, 1875, in Wamego, Kansas, to Civil War veteran and locomotive engineer Henry “Hank” Chrysler and Anna Maria Breymann Chrysler, of German and Dutch descent. Walter was their third child, although their second died before the age of two. A daughter followed eight years later. Father Hank was a legendary engineer on the Kansas Pacific Railroad, later named the Union Pacific.

Life was rough on the then frontier: Hank’s trains had to deal with Indian raids, robbers, and washed-out bridges. He carried a six-shooter while driving his trains. Buffalo still roamed the prairies. Texas cattle were driven to the railhead towns in Kansas for shipment eastbound (until the Texas railroad system was later built out). Arriving cowboys mobbed the saloons, where gunslingers, gamblers, and painted ladies awaited them. Many townsfolk lived in houses made of prairie sod, but the Chryslers lived a bit better, in a wooden house with two rooms. Even so, winter snow blew into the Chrysler home through cracks around the windows. After Walter’s birth, the family moved to Brookfield, then on to Ellis, Kansas, before Walter was four years old. He would spend roughly the next fourteen years in Ellis, growing and learning.

Walter learned important values from his warmhearted father and tougher mother. His greatest thrill was an occasional ride with his father in the cab of a giant steam locomotive. By the age of twelve, he was a drummer in a band, and soon his mother started him on piano classes, one of the few boys in town to attend them. He later picked up the clarinet. Throughout his life, Walter could pick up almost any instrument and play it well, making him the life of many parties. A tuba became his constant companion. He played baseball well and loved to dance, hunt, and fish. He was among the best at playing marbles, even beating the old men. Walter was a perpetual jokester: decades later, visitors would sit on whoopee cushions in Chrysler’s mansion and even find fake plastic bed bugs in the guest bedrooms.

Walt showed signs of being an entrepreneur as he sold silverware door-to-door and sold his family’s excess milk to neighbors. Since no one paid for the milk until payday, he kept a pocket notepad listing his accounts and amounts due. For the rest of his life, Walt had a pocket notebook listing financial data—later, the costs of manufacturing each automobile.

Walter was not a particularly good student. He was more interested in the mechanics of machines like the steam locomotive. History is not clear on whether he received a high school degree, but by fifteen he had had enough of school. At sixteen, Walt started work as a delivery boy for a local store. He worked from 6 a.m. until 10:30 p.m. each day, for $10 a month. By seventeen, he wanted to get an apprenticeship at the railroad shops in Ellis, but his father resisted, hoping Walter instead would be the first member of the family to attend college. The pig-headed boy would not hear of it and got on with the Union Pacific shops as a floor sweeper for ten cents an hour in 1892. After proving his work ethic and ability to get along with others for six months, his bosses convinced his father to let Walter enter the apprentice program. Walt was on cloud nine, even though this meant a pay cut, to five-and-one-half cents an hour.

One other thing obsessed the young Walter Chrysler: the beautiful Della Forker, daughter of the owner of the town’s meat market and slaughterhouse. Walter had first seen her in his piano classes. She lived in the nicest house in town and was familiar with “the finer things.” She was described as, “a petite creature with dark, mysterious eyes set in creamy porcelain cheeks framed by rivers of lush auburn hair.” Walter and Della were sweethearts “from the beginning.” Della would go on to be one of the most important parts of Walter Chrysler’s life until the day he died.

Man on the Move: Gaining Experience

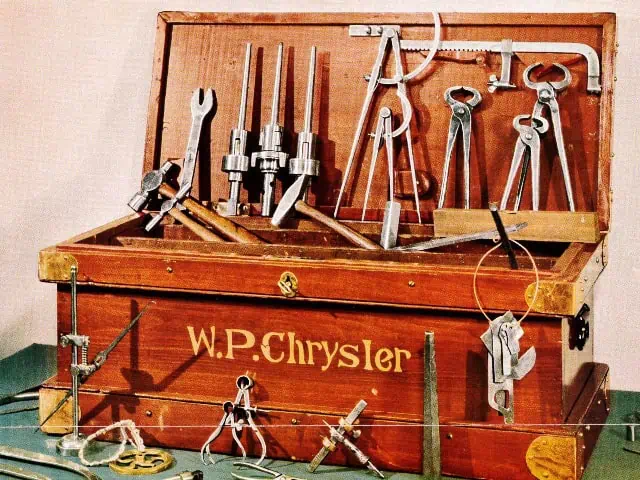

As an apprentice in the Union Pacific shops, Walter absorbed everything. He had “an unquenchably curious mind.” He talked to the “old pros” and tried to learn everything they knew. It was required that the budding mechanics make their own tools. Since they worked on the huge locomotives, these tools were often big, forged of sturdy steel. Walter wasn’t satisfied with the shop’s depth gauges that only measured down to one-sixteenth of an inch, so he built his to an accuracy of one-thirty-second of an inch. Walter’s toolbox stayed with him the rest of his life, later being displayed on the observation deck at the top of the Chrysler Building.

Walter did not limit his education to what he learned in the shops and at the locomotive roundhouse. He began to take correspondence courses from the International Correspondence School, a habit he continued for many years. Above all else, he read Scientific American magazine from cover to cover. He learned of the invention of railroad air brakes by the Westinghouse Company, and then became the local expert as his railroad began to use the brake system. Walter peppered the magazine’s editors with questions. The November 5, 1892, issue carried answers to five of his questions. When he asked if there were two acids that would explode when combined, the answer was a terse, “Yes.”

The young mechanic was of course in the prize-winning Union Pacific band. One of his proudest achievements was building a working 28-inch model of the steam engine his father drove, impressing everyone in town.

Walter’s income rose to $1.50 a day, but it was not enough for him to marry Della Forker, though they had become engaged. Beginning a long string of seeking new opportunities, he jumped at the chance for a better job with the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad in Wellington, Kansas. While all of Della’s friends were getting married to local boys, she was so devoted to Walter that she encouraged him to move away and fulfill his ambitions; she would wait, alone in Ellis.

As a journeyman mechanic on the Santa Fe, Walter’s pay jumped to 27.5 cents an hour. The twenty-two-year-old was soon fixing problems that none of his supervisors could fix. But he missed Della and Ellis, and soon returned to the Union Pacific there as the night mechanic at 30 cents an hour. He told Della, and only Della, that his real dream was to become the master mechanic in a railroad shop somewhere. He remained ambitious, restless, and hungry for more experience. Della understood.

Walter’s ambition next led him to Denver, working for the Colorado and Southern Railroad. He hated the “wild and reckless” town and quit after two weeks. Next came Cheyenne, Rawlins, and Laramie, all in Wyoming. Walter continued to learn new skills, new shop methods, and the vagaries of different locomotives. He took off enough time to attend the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. His next job was in Salt Lake City, a town he liked. But he still missed Della. Finally, in 1901, five years after they had become engaged, Della Forker became Mrs. Walter Chrysler. They moved to Salt Lake City using the $60 Walter had saved from his $3 per day/30 cents an hour wages.

Walter and Della

February 1902 was an important month for the twenty-seven-year-old Walter Chrysler. He was promoted to roundhouse foreman, overseeing ninety men, most of them much older. And Della gave birth to the first of their four children, Thelma.

His reputation as an outstanding mechanic and problem-solver spread among the many railroads, and in 1903 he and Della moved to booming Trinidad, Colorado. Walter became the general foreman of the Colorado and Southern’s shops there, boosting his income by $15 a month. This was a major step upward in management authority. For the next twenty-one months, Walter Chrysler worked around the clock, improving the facilities and practices of the shops.

Walter became an excellent but demanding leader of men. They always knew he could do their job as well or better than they could and that he never hesitated to do so. The man was always ready to roll up his sleeves and get dirty, to work alongside his men, to do whatever it took to keep the trains running and on time. At twenty-nine, the one thousand workers who reported to him called him “the old man” out of respect.

George Cotter was the general superintendent of the division of the railroad that included Trinidad. That meant Cotter was the supreme leader of all aspects of the Colorado and Southern over any miles of track. One day Cotter arrived in Trinidad in his private railroad car. He invited Walter to lunch in his car, but Walter turned him down, saying he was busy and already had his lunch packed. But the real reason was that Walter was insecure about how to act in such fancy surroundings with such powerful people.

Finally, Cotter grabbed him and hauled him into the elaborate private car. The black waiters rolled their eyeballs at Walter in his filthy working clothes. The railroad executives at the finely set table rolled with laughter when Walter tried to chew a tamale, cornhusk and all. He had never seen one before. While Walter Chrysler could have a hot temper at times, he held his tongue. He became friends with Cotter, dining with him every day for a week. These experiences made Walter realize there was a much bigger world out there, beyond anything he had experienced or mastered.

As always, Walter Chrysler made friends in Trinidad, and kept them for life. Several of his co-workers there later became Chrysler Corporation employees or car dealers. He never forgot anyone. And of course he made music and enjoyed life.

Three months after their meetings in the private car, Cotter offered Walter an even more important opportunity—to rebuild the shops and run them on the Fort Worth and Denver City, a sister railroad of the Colorado and Southern. The shops were in the small village of Childress, Texas, in the Texas panhandle. The meant living in a much rougher town than Trinidad and Walter worried that Della would not be happy. But she cut off his concerns, saying she wanted to go wherever he needed to go in order to move ahead. They moved to Childress, where Walter continued his stellar performance as a railroad mechanic and manager.

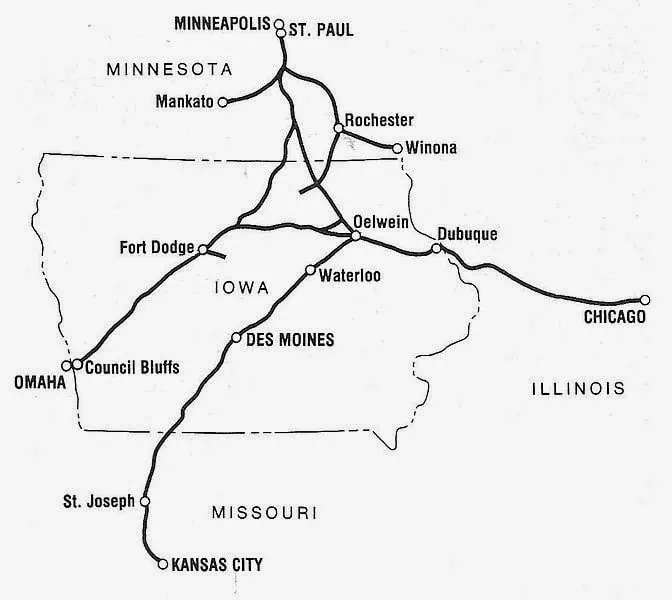

Then, in late 1905, the thirty-year-old Chrysler’s big dream came true. He was offered the job of master mechanic at the excellent main shops of the Chicago Great Western Railroad at Oelwein, Iowa. The pay was $200 per month, a 25 percent raise. As had often been the case, his superiors, including Cotter, urged him to take the better job and wished him well.

Oelwein, Iowa: Top Management Responsibility

Walter Chrysler had never seen a railroad shop as big as the Chicago Great Western’s main shops at Oelwein, where he took charge in January 1906. The shops were so big that they could hold sixteen locomotives at a time. Walter and Della’s second daughter, Bernice, was born three months later, just after Walter turned thirty-one. By May of 1907, thirty-two-year-old Chrysler’s performance earned him a promotion to superintendent of motive power, giving him authority over all the locomotives, both in the shops and out on the line. He played a critical role in keeping the railroad running safely and on time.

In 1908, Walter went to Chicago to see the auto show there. His imagination was fired by the beautiful, top-end Locomobile. He wanted it like he wanted few other things in his life. He saw the automobile as the future of transportation, challenger to the railroads, though most everyone else saw it as only a rich man’s toy, possibly a passing fad. Chrysler later wrote of the experience, “I did not simply want a car to ride in. I wanted the machine so I could learn all about it. Why not? I was a machinist and these self-propelled vehicles were by all odds the most astonishing machines that had ever been offered to men.”

The problem was that the car cost $5,000, while his lifesavings were just $600 and his annual salary $2,400. He begged and begged a Chicago banker friend for a loan. Chrysler said to the banker, “The railroads have made this a richer country, haven’t they? . . . Just ask yourself what this country will be like when every individual has his private railroad and is able to travel anywhere.” He finally got his loan when a senior Chicago Great Western official agreed to co-sign on it.

The white Locomobile with red upholstery arrived in Oelwein by railroad. Horses pulled it to Walter’s garage. Not only did he strive to understand how it worked; he took it completely apart and put it back together at least forty times! Only after three months did he feel comfortable enough with the car to give Della the ride she had been begging for.

Walter worked nights and weekends on the car, all the while putting in long hours in his railroad job, exceeding the company’s expectations and winning the loyalty of his colleagues. He became known for his ability to match the right man with the right task. Friends later said of Chrysler that not only was he technically very smart, but that he also had intuition, “almost like a woman.”

A New Job: ALCO

Management of the Chicago Great Western soon changed hands, to people who did not get along with Walter as well as the old team. When needlessly called on the carpet in December 1909, he quit.

Also in 1909, Walter and Della’s first son, Walter Junior, was born.

In his job at the railroad, he had been in charge of selecting and ordering locomotives and many parts and tools. Thus, when he was back on the job market, he was snapped up quickly by the American Locomotive Company (ALCO), one of the two largest steam locomotive builders (alongside Philadelphia’s Baldwin Company). ALCO put him in charge of its struggling Pittsburgh works at a big pay hike to $275 per month ($3,300 per year).

Though it was his first time at running a manufacturing plant, Walter soon had the Allegheny works making money and booking million-dollar locomotive orders, up to twenty-five at a time. By 1911, his pay was up to $8,000 per year, equal to $230,000 in 2020 dollars, placing the Chrysler family near the top of the heap financially. The Chrysler family upgraded to a much bigger house in Pittsburgh, and Walter moved up to a fancier Stevens-Duryea automobile. Then came the most important career move in Walter Chrysler’s life—and one that led to a loss of income for the next few years.

Here we must take a brief step back in auto industry history. In 1908, Flint, Michigan, carriage and buggy maker William “Billy” Durant had created the General Motors Corporation (GM) out of the Buick company, which he already owned and had made a major success. From 1908 to 1910, Buick was the second-best selling car, narrowly behind Ford, with each selling up to thirty thousand cars a year (after that, the Ford Model T took off, its sales growing geometrically). Billy was a great salesman and had big visions. But he was not an organized manager; he was a speculator and wheeler-dealer. He bought up Cadillac, Oldsmobile, and many other companies, usually for stock instead of cash. By 1911, frustrated Eastern bankers had taken control of General Motors away from Durant.

Among the leaders of that group of bankers was Bostonian James J. Storrow (after whom Storrow Drive in Boston is named). Storrow briefly served as president of GM. He and his comrades worked to put the company on a more solid footing, including finding strong managers. Storrow also happened to be on the board of directors of ALCO. His talent search led him to Walter Chrysler. Storrow put Walter in touch with the head of the key Buick division, a man named Charles Nash. An outstanding production man, Nash had risen from even lesser beginnings than Walter Chrysler.

Walter was intrigued at the opportunity to go into this new industry. He and Nash dickered over pay. Soon, ALCO got word of this, and its bosses offered Walter a 50 percent pay increase, to $12,000 a year. When Walter told Nash about this offer, Nash said he could only pay half that, $6,000, 25 percent less than Walter was already making. Chrysler did not take long to say yes to Charles Nash, however. Della didn’t blink at the pay cut. His new job was as works manager for the massive Buick plants in Flint. Chrysler and Nash remained friends for life.

In January 1912, just before the family left Pittsburgh for Flint, Jack Chrysler, their second son, was born.

The Buick Years

The discipline Walter had learned at the railroads and ALCO and his endless self-education soon paid off. He found out that Buick did not really know how much each car cost to produce, at least not at the detail he required to understand the business. Out came one of Walter’s precious notebooks, soon filled with daily and monthly cost averages. Problem solved.

An example of how loosely Buick was run prior to Chrysler’s arrival is informative. Each day, test drivers took new Buicks out onto the streets of Flint to test them out. Walter noted that more cars went out than came back. One to four cars a day were going missing! Chrysler put in place a system to track the test cars. He calculated that he saved Buick his first year’s pay within his first week at Buick.

When Walter then applied what he had learned to the design of new cars, the GM board did not believe that he could bring costs down that much. But he did better than even he projected.

For the next three years, Walter was at the plant night and day, not even taking off one evening for a night out with Della. But as always, she stood behind him and encouraged him on. At every turn, Walter made Buick more efficient, faster, and more profitable. When he joined Buick in 1912, the company sold about twenty thousand cars. Four years later, they sold 124,000, more than double the other GM brands combined.

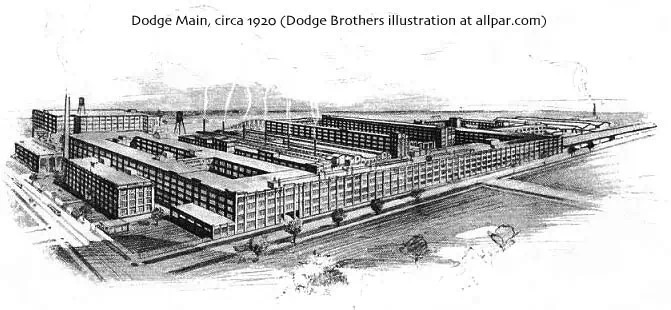

“Buick City” was huge, including the largest automobile manufacturing plant under one roof. The engine plant alone was 782 feet long and 360 feet wide, covering six acres. All the Buick buildings combined totaled 2.5 million square feet, about 57 acres. In 1913, the five thousand workers were turning out about 170 cars a day, twice the per-worker productivity of some competitors. Buick made all its major parts. (The Ford was assembled from key parts made by others, primarily the Dodge Brothers.)

Buick had in 1910 adopted the excellent advertising slogan, “When better automobiles are built, Buick will build them.” Walter Chrysler and Charles Nash turned this slogan into a fact. Walter was key to this era of rapid development at Buick, including the company’s first use of electric starters, replacing the dangerous crank. (The electric starter had been perfected for Cadillac in 1912 by Charles Kettering’s Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company, called DELCO and later acquired by GM, which also acquired the technical genius Kettering.) Lighting systems, engines, and many other parts of the Buicks got better and better.

Walter Chrysler said, “All I am is just a man who wants things done and done quickly. Give me a quick decision, even if a mistake happens. That’s all right. The same mistake won’t happen a second time.” But he was also an inspiring leader, earning tremendous loyalty among the thousands of workers. He was a leader who knew what it was like to do the hard work, to pour muscle and sweat into every effort. Walter improved lighting in the plants. He made sure there was plenty of fresh water for the workers to drink. Nurses were on duty at all times. Because Flint grew so fast, many workers lived in shanties; Walter worked to build affordable, decent housing for his people. His pride in the Buick workforce was illustrated in an amazing photograph he staged in 1913. Every Buick worker was called out in front of the plants for the photograph.

For three years, Walter did not get a raise. Being well aware of how profitable he had made Buick, in 1915 he finally demanded a raise, threatening to quit if he didn’t get it. He told Nash he wanted $25,000 a year ($600,000 in 2020 dollars), eliciting a screech from Nash, “Walter!” But Nash talked to Storrow, and two days later Walter got his raise. When Nash told him, Chrysler said, “Next year I want $50,000!” The man was patient, but he also knew his worth to the organization. He was pig-headed when he needed to be.

Also, in 1915, Billy Durant regained control of GM, in a most roundabout way. After being run out of the company, he had worked with race car driver Louis Chevrolet to design a new affordable car. Priced higher than Ford’s Model T but with far better features, the car was a hit. Durant sold Chevrolet stock to the public and the stock rose in value quickly. Then Durant offered to exchange his holdings of Chevrolet stock for GM stock in a deal that was very attractive to GM stockholders. Fighting off the Eastern bankers, with the financial support of the DuPont Chemical family, Billy got back in control. (Briefly, Chevrolet actually owned General Motors, but that was quickly reversed, Chevrolet becoming a GM division alongside Buick, Cadillac, Oldsmobile, and Oakland, soon to be renamed Pontiac.)

Walter Chrysler always liked Billy Durant personally but had no patience for his disorganized management style. Neither did Charles Nash, who had been elevated to the presidency of GM but quit when Durant returned to power. Nash took over the old Jeffery Company, maker of Rambler bicycles and then automobiles (in Racine, Wisconsin) and renamed it Nash Motors.

Walter considered joining Nash in his new venture, but Billy Durant got word of their plans. Calling Chrysler into his office, he offered him the astounding salary of $500,000 a year and the presidency of Buick. Walter was stunned. Yet he still told Durant that he could only accept the offer if he had full control of Buick, with no interference from Durant. Billy assured him of full power, and Walter became Buick’s president on June 7, 1916, at a pay level equivalent to $12 million a year in 2020. Walter also received stock in General Motors and was elected to the company’s board of directors. He was now near the top of one of America’s largest, most important companies.

Chrysler later said of Billy Durant, “I cannot hope to find words to express the charm of the man. He has the most winning personality of anyone I’ve ever known. He could coax a bird right down out of a tree, I think.”

But when Durant announced that “his” GM was building a big automobile frame plant in Flint, Chrysler hit the ceiling. Durant had not told Walter of these plans. Walter Chrysler had become a leading citizen and booster of Flint and knew the city did not have enough housing to meet present needs, let alone those created by a big new factory. Walter had also already signed a five-year contract with a supplier to build the frames for much lower cost.

This conflict was one of many in which Durant went back on his word to stay out of Walter’s way at Buick. Durant always offered Walter higher pay to soothe him, but Chrysler was more interested in controlling his own destiny—and that of his workers—than making more money. On November 1, 1919, Walter Chrysler left General Motors for good. Billy Durant bought back Walter’s GM stock for $10 million ($150 million today!).

In one last task for GM before he left, Walter traveled to France with the top management of the company. General Motors was considering buying French automaker Citroen (but decided against it). Della went along, a bit of pay-off for her long days and nights of missing Walter. Equally important, Walter made new friends that he held for life: Andre Citroen, Albert Champion of spark plug fame (Champion and AC), and Alfred P. Sloan. Sloan would take over GM when Durant was later run out once more and turn it into the greatest industrial enterprise of the twentieth century through his organizational genius. (Billy Durant again made and lost a fortune, but by old age was dependent on handouts from old friends like Sloan and Chrysler.)

Forty-four-year-old Walter Chrysler could have retired if he had wanted to, but …

Independence

The year is 1920. The auto business is booming, led by the sale of over four hundred thousand Model Ts. Walter Chrysler was friends with every automaker and every parts supplier. All considered him a miracle worker, a unique talent in the industry. The best-informed “knew” that the industry would become dominated by two companies: General Motors and Ford. Yet that did not stop other dreamers from trying to catch up to those two giants.

Among those dreamers was John North Willys, who was a dealmaker not unlike Billy Durant. Willys had started as a car salesman in upstate New York, then buying the troubled Overland car factory in Indianapolis when he could not get as many cars as he could sell. Willys–Overland made and sold a lot of cars, ranking second in the industry behind Ford from 1912 to 1918, and usually in the top five after that. But the company was not an efficient producer, rarely as profitable as other auto companies. Willys’s investors and bankers grew concerned and sought someone to turn the company around. Without a “savior,” all would be lost.

Thus, in 1920, Willys met Walter Chrysler’s demand for a salary of one million dollars a year for two years, and Walter took “full control” of the Willys company. He moved his family to New York, where Willys was headquartered and where Walter would live for the rest of his life. Yet, as with Durant, Walter soon found that his control was limited, with infighting between the investors and Willys hanging over the company’s head. Chrysler learned a great deal about finance in the process, but also began to search out other opportunities, where he could have the true independence of action that he so desired. Also during these years, Chrysler dabbled in the idea of creating a wholly new Chrysler car. He worked on the idea of a better car with three former Studebaker engineers whose work he had come to respect: Fred Zeder, Carl Breer, and Owen Skelton. These three went by the moniker ZSB because they did not want anyone calling them anything with “BS” in it. But they became known in the industry as “The Three Musketeers” because they always worked as a team, balancing each other’s specialized skills. For the time being, nothing came of the new car idea, though the Musketeers continued working on it.

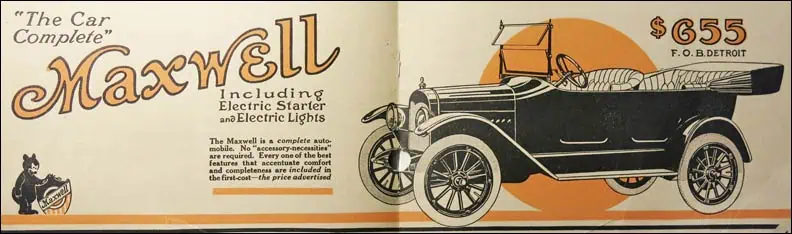

Another ailing automaker that was searching for leadership was the Maxwell Motor Company, which began making cars in 1904. The Maxwell was known as a good but outdated car. The company had been one of the top six automakers from 1906 through 1911 and remained in the top ten through 1919. In 1920, it was eleventh, selling thirty-four thousand cars (vs. eighty thousand the prior year). The company’s glory days appeared to be over. Worse yet, in late 1920, demand for cars dropped dramatically. A brief recession in 1921 spelled doom for many of the weaker car makers. Despite all efforts to save it, Willys went into receivership (bankruptcy) in November 1921. (The Willys company survived and went on to make the famous Jeep.)

Into this picture steps our story’s hero. The Maxwell company’s backers approached Walter about helping them out. Given his experience at Willys and his awareness of Maxwell’s problems, Walter was reluctant. Nevertheless, he became an advisor at the “measly” pay of $100,000 a year in 1920.

In May 1921, Maxwell was reorganized with a new stock and ownership structure, with Walter Chrysler as chairman of the board. Maxwell’s backers ensured that he got a lot of inexpensive stock in the company.

At Maxwell, Walter at last found the total control of operations that he had long sought. He moved quickly to move out the old, outdated cars and began developing better ones. Applying his great judgment of men and his many friendships in the business world, he gradually put together a team of outstanding executives in finance, marketing, and production. There was no aspect that escaped Walter’s diligence.

Under Walter, Maxwell sold 16,000 cars in 1921, 44,000 in 1922, 67,000 in 1923, and 79,000 in 1924. Revenues in 1924 exceeded $70 million and profits were $6 million. Even then, the company still ranked only ninth among automobile makes, behind Ford (at 1.7 million Model Ts), Chevrolet, Dodge, Willys–Overland, Buick, Hudson, Durant (trying again), and Studebaker. Walter Chrysler was a long way from being a major player in the industry.

Chrysler was, nevertheless, extremely wealthy by now. He bought a perfectly manicured 12-acre estate at King’s Point, Great Neck, on Long Island Sound. The estate included a 23-room mansion, 82-foot swimming pool, 8-car garage, and 150-foot pier out into the sound. Della loved the home and filled it with valuable art and furniture, much of it acquired on trips to Europe. Walter had always loved boating and fishing. He began buying yachts, ultimately commuting to his Manhattan office on his yacht in the summer. (Today the estate is the US Merchant Marine Academy.)

ZSB—engineers Zeder, Skelton, and Breer—had gone off to start an engineering consulting firm, which struggled along. However, they continued to tinker with the idea of a Chrysler car, even when Walter was busy with other things and showed no interest in proceeding. Ultimately, they caught his enthusiasm and he decided to move ahead with the project. The Three Musketeers then joined Maxwell and remained with the company, soon to be renamed, for the rest of their careers.

In 1924, the Maxwell Motor Company introduced the six-cylinder Chrysler Six. It was the first American car to have a high compression engine, first with four-wheel hydraulic brakes, first with an oil filter and air filter, first with an emergency brake, and first with both temperature and fuel gauges on the dash. Even much higher-priced luxury cars did not have these features. In short, it was revolutionary compared to the competition.

The Chrysler Corporation: 1928, the Year Everything Changed

The Maxwell Motor Company was renamed the Chrysler Corporation in 1925. By 1927, the Chrysler make was selling 182,000 cars a year, seventh in a field now led by Chevrolet. (Henry Ford gave up on the badly outdated Model T in 1927 and shut down his factories to retool for his forthcoming Model A.) Chrysler Corporation sales reached $173 million in 1927 and profits $22 million. Walter was moving up in the auto world, but still not near the top.

The year when everything changed was 1928. Walter Chrysler had one of the most remarkable single years in the career of any businessperson in American history. Four spectacular events occurred that year.

- On May 30, Walter Chrysler announced that the Chrysler Corporation was acquiring the far bigger Dodge Brothers company for stock (no cash).

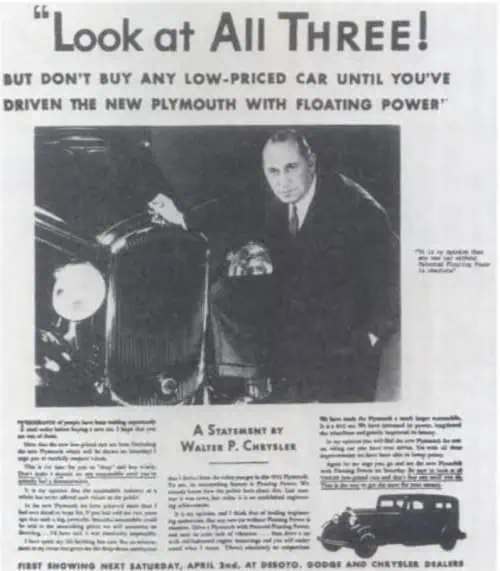

- On July 7, aviatrix Amelia Earhart drove the first Plymouth into Madison Square Garden. The $670 car was Chrysler’s first entry into the low-priced field where the most cars were sold, taking on Ford and Chevrolet, both already well established.

- On August 4, the company introduced the mid-priced DeSoto, letting the world know that they were following Sloan’s model at GM of “a car for every purse” rather than Henry Ford’s single brand approach. The Chrysler make remained at the top of the company’s offerings.

- On October 16, Walter Chrysler announced that he was going to build the tallest building in the world, the Chrysler Building in New York City, as a family investment. Despite being surpassed in height by the nearby Empire State Building within a year of completion, the Chrysler Building remains one of the world’s great art deco monuments.

In just one year, fifty-three-year-old Walter Chrysler had changed the auto industry from “the big two” to “the big three.” Industry analysts had thought this impossible, since both major competitors had been in the auto business for at least twenty years. Even Hudson, Studebaker, and the luxurious Packard cars had a long head-start.

It is no wonder that Walter was named Time magazine’s 1928 Man of the Year, only their second one, following Charles Lindbergh in 1927.

Each of these developments has a story behind it. Most important to the company were the acquisition of Dodge and the introduction of the Plymouth.

The Plymouth had been working away in Chrysler’s mind for years. He knew he could never be a major force in the industry without a low-priced car. Two years before the Plymouth’s introduction, key executive KT Keller had agreed to go to work for Walter only if he was committed to producing such a car. Keller became Walter’s right-hand man, and later succeeded him as head of the Chrysler Corporation. Working closely with ZSB, the company team applied the company’s advanced engineering and ideas in the new car.

Legend is that Walter drove the first Plymouth off the assembly line straight over to show it to Henry Ford and his son, Edsel. Henry reportedly told him, “Walter, you’ll go broke trying to get into the low price market. We and Chevrolet have that market sewed up.”

Once the Plymouth was launched (and soon a huge new factory built to produce it), Walter’s marketing instincts came into play. He ran ads in all the major magazines crying out, “Compare All Three!” This left no doubt in the public’s mind that he meant Ford and Chevrolet, which sold by far the most cars in the land.

The acquisition of Dodge was equally important and requires a bit more background.

The Dodge brothers, Horace and John, were wild men, known for drinking and partying hard, even shooting up bars. But they were also excellent machinists, which led them to making most of the major parts for Henry Ford’s Model T. Under their deal with Henry, they could make no cars of their own. They took stock in the Ford Company for partial payment of their services and were major creditors of Ford. Over time, Henry tired of having investors and ultimately borrowed millions to buy out the other investors, including the Dodges. He also began to build more of his own cars, rather than just assemble parts made by others like the Dodges. When the dust all settled, the Dodges had millions of dollars and severed their relationship with Ford, allowing them to start producing their own cars in 1914.

The Dodge car was renowned for its reliability, thus being called a “doctor’s car” or a “salesman’s car.” The huge “Dodge Main” factory in Hamtramck, Michigan, next to Detroit, became one of the largest car factories in the country. The Dodge company was extremely successful.

But then, in 1920, both brothers died. Their widows soon sold the business to Wall Street interests, who did a mediocre job of overseeing the company. By the spring of 1928, the Dodge brand was still respected but had lost much of its luster. The Wall Streeters approached Walter Chrysler about taking Dodge, much bigger than Chrysler, off their hands. As much as Walter wanted the large production facilities for his growing Chrysler Corporation, he fought a hard bargain, paying the price he wanted, getting the stock and cashless deal he wanted. He got all that, and the deal closed on July 31, 1928.

The DeSoto story is shorter. To understand it, we need to understand Walter’s business strategy.

Walter and Della were close friends (and Long Island yachting lovers) with Mr. and Mrs. Alfred P. Sloan, head of General Motors, ever since their Paris trip to inspect Citroen. Sloan’s idea of a car for every purse and purpose, from Cadillac at the top to Chevrolet at the bottom, had propelled GM to the top of the industry. The three brands in the middle price range—Buick, Oldsmobile, and Pontiac—generated large sales and profits for GM even into the 1970s.

Walter understood and loved this strategy, so different from the approach of Henry Ford, who stuck with his inexpensive Fords and did not introduce the mid-priced Mercury until 1938. (Ford had bought the upscale Lincoln in 1922, but it was never a large factor in the industry.) By acquiring the Dodge brand and adding the Plymouth and DeSoto in just over ninety days of each other, the Chrysler Corporation exploded from being a one-trick pony (Chrysler) to having four makes of cars covering the full range of affordability.

The last of 1928’s big announcements, the Chrysler Building, is of course a story in itself. Walter’s children were not interested in the auto business, but he wanted them to have something to do, and certainly something to inherit. He also believed in real estate and believed in New York City. The building project at 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue was already planned, but the developer was unable to arrange financing when Walter and his banker friends stepped in. At first, it was just an investment for Walter, and he did not spend much time on the building’s design. But when he saw models of it, he declared that the planned lobby was too claustrophobic for such a grand building. After that, he got very involved, making sure every surface was beautiful, that the Cloud Club near the top was the ultimate city dining room, and setting up his own office at the top. The ceiling mural in the lobby is one of the biggest paintings ever made.

Other skyscrapers were going up fast in New York at the end of the roaring twenties. To ensure that his building was the tallest, Walter had the architects add a spire to the building, which was hidden from public sight until raised up, in a few hours upon the building’s completion in 1930. The Chrysler Building thus replaced the Eiffel Tower as the tallest manmade structure on earth. While the Empire State Building took away that honor within a year, Chrysler’s building was effectively leased up before the stock market crash and was thus more profitable than the Empire State, which struggled to fill up. (The Empire State Building was a project of the same DuPont interests which controlled General Motors.)

Built at a cost of about $14 million ($220 million today), the Chrysler family continued to own the building and collect its profits until 1953, when Walter’s children sold it for $18 million.

The Thirties: Performing Unlike Any Other Car Company

Just as Walter was completing these moves and consolidating his newly enlarged company, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression began. Ford Motor’s profit declined from $88 million in 1929 to a $2 million loss in 1933. The far stronger General Motors went from $265 million profits in 1929 to a low of under $9 million in 1932. Chrysler was hurt as well, going from his 1928 peak profit of $34 million to an $11 million loss in 1932.

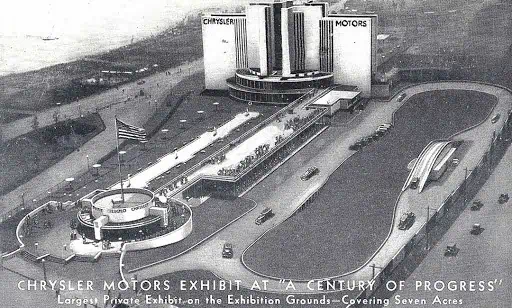

But then things began to change. Walter and his excellent team never lost faith in their company and their abilities. They continued to invest in new plants and processes. They developed new, better-engineered cars. They built one of the biggest and flashiest exhibits at the Chicago Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1933 and promoted their cars at other fairs. In 1935, Chrysler was the only major automaker to sell more cars that it had sold in the boom year of 1929. By 1936, the company’s annual profit was $69 million, its highest yet, and dwarfed Ford’s $18 million. (GM was back on top at almost $240 million.)

The year 1937 saw the Chrysler Corporation produce a record one million cars. The company was thus the second-largest car producer after General Motors (1.8 million cars), but bigger than Ford. It held this second-place position until the early 1950s.

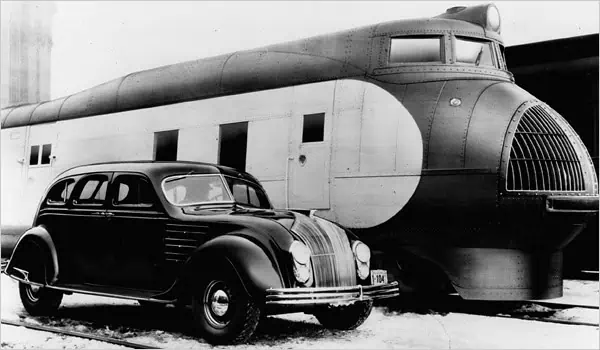

This era saw a flurry of new products from all these companies, often redesigned to reflect the new era of streamlining. Among the most advanced of these cars were the aerodynamic 1934 Airflow cars developed for all the Chrysler lines. Though the car had many new features, it came off the production lines slowly and with quality issues. The public also had limited ability to digest such radical styling. While not a big success at the time, it is considered a design icon of the era and is today highly collectible.

Yet all was not rosy. Any student of American history knows the suffering of workers in the Depression and the labor strife that resulted. One can fill a library with the books on these events. In the auto industry, there were great stresses over who should represent the workers. The older craft unions had little use for the “lowly” line and assembly workers. Unions fought over who would rule. Henry Ford hated the unions and people died in conflicts at his factories. While GM management may have been equally wary, they avoided violence. GM was hit by massive sit-down strikes in Flint, Michigan; Anderson, Indiana; and other plants in 1937. These sit-downs were illegal, but the federal government, governors, and even company management were reluctant to resort to force to end them. The strikes dragged on until labor and company leaders were able to resolve their differences.

Dodge Main was hit by a sit-down strike later in 1937; within a few minutes of being announced, the entire plant shut down. Some workers were hesitant, given their tradition of mutual respect with Walter Chrysler, who was always ready to greet them and sit with them in the workers’ cafeterias. Negotiations were intense, going on around the clock. Though Walter Chrysler had passed the company presidency on to KT Keller in 1935, he remained chairman of the board and the face of the company, so he was the company’s lead negotiator. When Walter appeared on a balcony during those negotiations, union workers driving by in a mass labor protest cheered him. Finally, the issues were resolved, the plants re-opened, and Walter and the union leaders gained a grudging respect for each other.

By the end of the 1930s, Walter Chrysler was increasingly “retired,” leaving the day-to-day management of his company to his trusted lieutenants. His ability to select men and give them power never abated.

The Company after Chrysler

In the early 1950s, Walter’s successors were slow to adopt the long, low auto profile driven by GM’s legendary head of design, Harley Earl. The company lost market share but then regained some back when it also went long and low in the late 1950s. Yet the company was stuck with the number three position for decades, suffering as a result. Chrysler could not realize the economies of scale at GM and Ford.

The company’s 1987 acquisition of American Motors, which had resulted from the 1950s merger of Nash and Hudson, brought with it the great Jeep brand. Some Chrysler innovations, like Lee Iacocca’s 1984 minivan, were successes. But the company struggled on, with repeated “turnarounds,” bankruptcies, billions of dollars in losses, and even a government bailout or two. Control passed to the German Daimler–Benz Company in 1998, then to private equity firm Cerberus Capital in 2007. Nothing worked; all seemed lost.

Then, in 2014, the long-troubled Italian auto giant FIAT took over. Most felt this was the end for sure. But under FIAT’s brilliant leader, Sergio Marchionne, Chrysler regained its mojo and went on to more success than it had seen in decades. In 2019, Fiat–Chrysler was the US’s fourth leading car company, selling 2.2 million cars, behind GM, Ford, and Toyota. Jeep (the original SUV) and Ram trucks (formerly branded as Dodges) are two of the strongest American makes. In 2019, 633,000 Ram pickups were sold, making them the second best-selling vehicles in America, after Ford’s F series pickups. Thus the legacy of Walter Chrysler continues, quite surprisingly, to live on.

Chrysler the Man

While Walter was achieving these amazing accomplishments in the auto industry, he was also living life. His biography is filled with stories of his parties, music, jokes, Long Island estate, retreat in Maryland, fishing and hunting, and many lifelong buddies. When he returned to any city he had lived in, from Ellis, Kansas, to Flint, Michigan, he was feted with greetings and banquets. Many called him the greatest and fairest man they had ever met.

In Ellis, he played marbles with his old friends upon arrival. These friends ranged from the richest and most famous celebrities in the world to the “lowliest” workers. He was always ready to lend a hand, write a check to someone in need, or find a job for a longtime acquaintance, often at the Chrysler Corporation.

Walter Chrysler was not perfect, he was human. He had a temper, but over the years he learned when to use it and when not to. His biographer refers to him as possibly being a functioning alcoholic, always a heavy drinker. And while he loved Della and always gave her credit for his success, his sexual appetites strayed. He gave one well-known “party girl” over $2 million worth of jewelry and financed her fancy apartment in New York.

On May 26, 1938, sixty-three-year-old Walter Chrysler suffered a stroke at home in New York. Just over two months later, his beloved Della died of a cerebral hemorrhage. A depressed Walter began to waste away, hanging on for two more years, until his death on August 18, 1940. Honorary pallbearers at his elaborate funeral included Alfred P. Sloan, Juan Trippe (the founder of Pan American Airways), and many other luminaries.

In 1928, Walter Chrysler was one of the most famous people in America, a national hero. Today, ninety-two years later, very few people know anything about him. We hope our story helps change that.

Gary Hoover

Executive Director

American Business History Center

Sources: This story is based on the outstanding and comprehensive biography of Chrysler entitled Chrysler: The Life and Times of an Automotive Genius, by Vincent Curcio (2000). Another excellent book, covering the history of the Chrysler Corporation before and after Walter, is Riding the Roller Coaster: A History of the Chrysler Corporation, by Charles Hyde (2003). For car buffs, a great book about the company’s automobiles, full of color pictures, is Chrysler, by Dennis Adler (2000). Walter Chrysler also wrote up his own story, Life of an American Workman, in 1937. The title appears to have been a response to Alfred Sloan’s magazine series of the same year entitled Adventures of a White Collar Man, later made into a book. Interestingly, both books were co-authored with the same writer, Boyden Sparkes.

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.