Preface: A Most Controversial Man

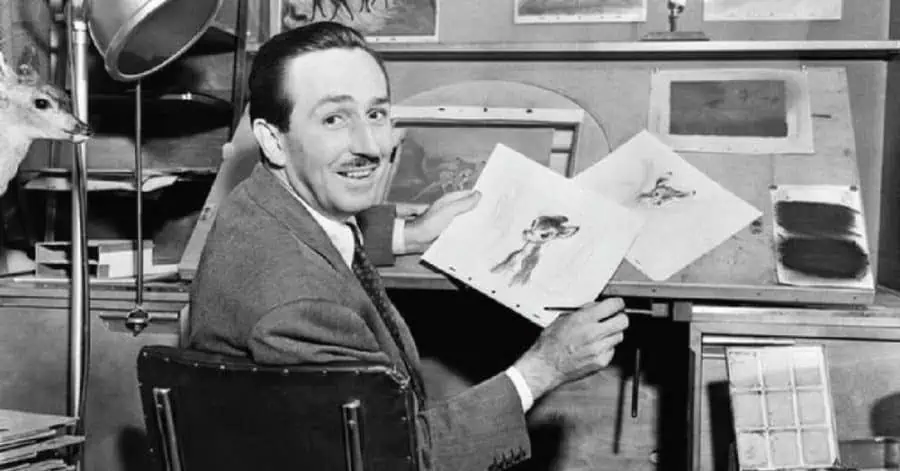

In this story, we address the life and work of Walter Elias Disney, one of the most famous men in the world. Telling this story brings special challenges.

Over the last two years, we at the Archbridge Institute have written the life stories of more than twenty “American Originals.” These men and women overcame great obstacles, including impoverished and troubled beginnings, to rise to “success.” They changed the world of their times and shaped the world that we live in today.

We estimate that several times as many books and articles have been written about Walt Disney as about any other American businessperson or entrepreneur. Libraries can be filled with the thousands of books and many biographies about him, which continue to be published over forty years after his death. Those books and articles each attempt to provide a different take on the man—from idolization to vilification. Was he one of the greatest geniuses our nation has ever created, or a soul warped by his abusive father, troubled by alcohol and other evils? Did he raise the standards of American media or did he damage our culture, promoting an unrealistic ideal of singing animals and happy families? Thousands of authors, scholars, and critics have waded into these waters.

Our research into his life and perusal of dozens of those books and articles is here joined with whatever wisdom and insight we’ve gained from our previous studies of great men and women. Other writers give great emphasis to his father, a strict disciplinarian and tough taskmaster who was quick to whip his four sons, of which Walt was the youngest. Yet we see this as a common pattern among great men one hundred years ago. For example, John D. Rockefeller’s father was an alcoholic. One author even wrote a book about the lives of great people, concluding that abusive or absent fathers were more the norm than the exception. We believe that Walt’s childhood challenges led him to a breadth of youthful experiences that many would treasure and that served the man well throughout his life.

From this complex family, Walt also received what may have been his “secret sauce”—an element that differentiated him from so many other great people—his loving, protective older brother Roy. Roy served Walt well, even beyond Walt’s death.

Walt Disney’s impact on American and world culture is another aspect that has motivated a great deal of “scholarly” studies and debate among critics. Many of those writers have a political viewpoint to express or a distrust of the tastes of the public. Had Disney and his productions not been so successful, most of those studies and books would never have been written. In contrast, few worry so deeply about the impact on society of Steven Spielberg or Warner Brothers.

Walt Disney from the outset only had one goal in mind: to entertain and engage the public, occasionally with a dose of education. He was clear that he created entertainment, not art. Walt Disney competed for the public’s approval with giant movie studios and, later, the powerful television networks.

No one was ever forced to watch what Walt produced, yet millions did and continue to do so. The astounding results speak for themselves. Walt’s DNA lives on today in the Walt Disney Company, by far the largest company in the media content-creation industry.

As we survey the great American entrepreneurs, Walt Disney stands out in interesting ways. If Henry Ford had not invented the affordable automobile, someone else would have. If Jim Casey had not developed accessible national package delivery at UPS, someone else would have. If George Eastman had not pioneered popular photography at Kodak, it would have nevertheless come along sooner or later. These and most other inventions were ones that society clearly needed. In most such cases, others around the world were already working on similar ideas and inventions.

But did the world desperately need a feature-length cartoon? Might the world have gone on for decades or centuries without the idea of the theme park? Those questions are unanswerable, but we think that Walt Disney’s dreams and visions were of a different nature than those of most entrepreneurs. He saw a world which no one else saw, and he made those dreams come true—for billions of people around the world. Thus, the title of this article: “Entrepreneur without Peer.”

With that context in mind, in the following paragraphs we try to answer the big questions: Who was Walt Disney? What was truly different about this man, whose name is likely to remain famous for generations to come? How did he evolve? What were his priorities and thought processes?

The Experiences of a Curious Young Man

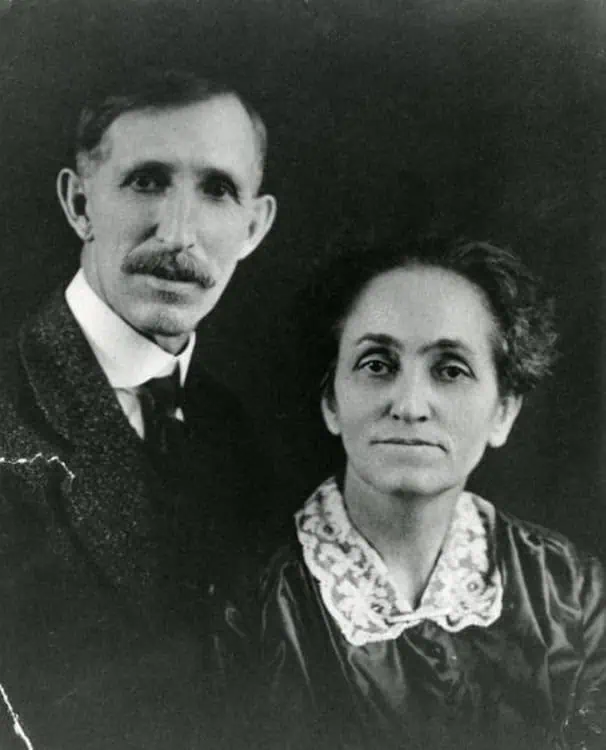

On New Year’s Day, 1888, twenty-eight-year-old farmer Elias Disney married nineteen-year-old Flora Call in Akron, Florida. Elias, ever (and unsuccessfully) in search of riches, sold his farm and bought a hotel in Daytona Beach. Their first son, Herbert, was born that December. But the hotel failed, and after other abortive attempts at prosperity, in 1899 the small family moved to Chicago, a booming city of 1.2 million. Elias, a good carpenter, started building and selling homes, but this, too, failed, so he took a job as a carpenter on the construction of the 1893 Columbian Exposition, one of the greatest and most attended World’s Fairs ever. Elias was later to tell his son Walter stories about the fair, known as “the White City,” perhaps inspiring dreams of Disneyland.

The family grew, adding Raymond in 1890, Roy in 1893, Walter on December 5, 1901, and Ruth in 1903. Elias, a strict, traditional man, came to believe that the big city was no place to raise a family. In 1906, when Walt was five, they moved to a farm in Marceline, Missouri, along the Santa Fe Railway line to California. While the family only stayed in Marceline for four years (until failure again forced the family to move on), those few years had an enormous impact on young Walt.

Walt was mesmerized by the countryside, the animals, and watching the powerful steam locomotives come and go. He loved to ride the backs of the pigs, a spectacle his father and neighbors enjoyed. Walt began to draw, his aunt bringing crayons and paper pads on her visits. Roy was protective of his younger brother; the two were always together.

Elias worked his sons hard. When they made any money on their own, he seized it from them, saying the family needed it. This was too much for the eldest sons, Herb and Ray, and they hopped a night train and fled from home. Elias also developed strong socialist beliefs, and became active in politics, ideas Walt ultimately rejected. After four years of effort, Elias fell ill and the family had to auction off the farm.

The next stop in Walt’s life was Kansas City, where the family arrived in 1910. Elias took on a newspaper route, but Roy and Walt did much of the work, delivering papers before school and collecting payments after. Eight-year-old Walt learned the streets of the city. He appreciated the warmth of apartment buildings in the winter. It was hard work, but Elias was relentless. He didn’t pay his sons for their efforts, telling them that their room and board was enough pay. Elias also had a quick temper. Finally, Roy had enough, and upon graduating from high school, left town like his older brothers.

Walt’s mother, Flora, made butter and sold the excess to neighbors. Walt was embarrassed when they went door-to-door selling to the families of his more affluent schoolmates. Stingy Elias, who would walk miles to save a nickel on trolley fare, told Flora not to use any butter at home, to sell all of it. So she buttered the children’s bread on the bottom side so Elias would not see it.

Despite his long hours of work, Walt found time to play with friends and to develop skits to entertain everyone he knew. He appeared at his own front door dressed in women’s clothes and even his mother did not at first recognize him. He created magic tricks, including an air-filled bladder that made dinner plates rise into the air. Walt and a friend developed songs and comic routines to amuse their schoolmates. The joy Walt got from performing, from making others smile, was a pleasant change from his sober, laborious home life.

In school, Walt was athletic, even winning a medal in track. But he wasn’t a very good student; the teachers said his “mind wandered.” He did love to read and spent much time at the library, devouring the works of Charles Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson as well as the Horatio Alger and Tom Swift stories.

And Walt kept drawing. When a teacher assigned students to sketch the flowers on her desk, Walt got in trouble for putting faces on the flowers and arms where the leaves should be. He earned free haircuts by doing caricatures of the customers at the local barbershop. When he was fourteen, Walt enrolled in classes at the Kansas City Art Institute. He read every book about drawing and cartooning that he could get his hands on. He might not have been a great student in regular school, but he loved to learn about the things that interested him.

Elias invested every penny in wild schemes, including a mining venture. None paid off. Frustrated, he and Flora moved back to Chicago where he invested in and worked in a jelly factory. Walt stayed in Kansas City to continue high school, living with his older brother Herbert, who had moved back to that city. Roy also returned to Kansas City and reunited with Walt.

The departure of their father gave the boys newfound freedom. Roy had previously worked as a “news butcher” on the Santa Fe railroad, selling soft drinks, popcorn, fruit, candy, newspapers, cigars, and tobacco on the trains. He suggested that Walt give it a try during the summer of 1917 and loaned Walt the required deposit of $15. Fifteen-year-old Walt said he was sixteen in order to meet the requirements of Kansas City’s Van Noy Interstate Company, which served several railroads.

Walt rode the trains of the Missouri Pacific, Kansas City Southern, and Katy railroads over a six-state area, reaching as far west as Colorado. In each town where the train stopped, Walt would get out and study the community. On long runs, he would stay overnight in hotels and boarding houses before returning to Kansas City. His greatest thrill was an occasional ride in the locomotive cab. He learned about the risks of business, losing money when customers threw his bottles out of the train windows. (Bottles were returnable for cash in those days.)

This must have been an extraordinary, eye-opening experience for the young explorer. But he never made any meaningful money, and at the end of the summer had to surrender the $15 deposit. (The Van Noy Company went on to become Host Marriott, today called HMSHost, which operates concessions in over one hundred US airports.)

That fall, in 1917, Walt decided to rejoin his family in Chicago and finish high school there. This was a fervent period of hard work and more art education in his “spare time.” The young man must have had an incredible amount of energy.

In addition to going to school, where he became a photographer and cartoonist for the school paper, Walt worked long hours. Elias did not approve of Walt’s spending time entertaining—or his dreams of becoming a cartoonist—but agreed to pay for correspondence art courses if Walt contributed to the family income.

Between the ages of sixteen, when he graduated from school, and twenty-two, when he departed Kansas City for Los Angeles, Walt Disney had more diverse experiences than almost anyone we have studied in our American Originals series. Given his intense curiosity, he must have learned a great deal from each of these new experiences.

Walt worked in the jelly factory where his father was a worker and investor, for seven dollars a week. He then took a better-paying job as a guard and watchman on Chicago’s elevated railroad. His first summer in Chicago (1918), Walt went to work at the giant Chicago Post Office. He was at first turned away because he was only sixteen, but when he drew lines on his face and returned in his father’s hat and suit, claiming he was eighteen, he was hired. At the post office, Walt worked twelve to fourteen hours a day, making deliveries and pick-ups, and driving trucks and horse-drawn wagons. It was hard work, but Walt loved seeing the city and working outdoors.

Even with his dedication to work, Walt found time to attend vaudeville and burlesque shows (which were “cleaner” then than they later became). He took notes on the jokes and gags, developing his own versions. He went to the movies and studied them. He watched the audiences’ reactions. Three nights a week he studied anatomy, pen technique, and cartooning in classes at the renowned Chicago Art Institute. His teachers included Chicago’s leading newspaper and political cartoonists.

By this time, World War I was raging in Europe. Walt’s brothers Ray and Roy were already in the military and Walt was eager to sign up, but at sixteen he was too young to enlist. He and a friend hatched a plot to run away and join the Canadian Army, which accepted younger men, but their plan was discovered and thwarted by their parents. Then the boys heard about the American Ambulance Corps, part of the Red Cross, which needed drivers. While this service also required recruits to be seventeen, the two lied and got in. Next, Walt needed a passport, which required his parents’ signature. Elias refused, saying it was a “death warrant” for Walt, but Flora forged Elias’s name, figuring that Walt was so determined that he’d run away if she didn’t.

Walt then got the influenza virus that killed millions around the world. Two of his friends died, but Walt recovered.

On December 4, 1918, Walt landed in France. A whole new world opened up to him as he explored the streets of tiny villages. He soon arrived in Paris. Walt drove ambulances but was also assigned to the motor pool—taxiing officers around Paris and later in a rural area. He learned every street and shortcut. As the war subsided, he worked alongside German prisoners, befriending some of them. Walt sold war souvenirs to make money to send home. He explored the countryside, drawing everything he saw. His year in France added immeasurably to his understanding of the world and to his maturity. (Ray Kroc, the man behind the rise of McDonald’s, also lied about his age, served in the ambulance service at the same time, and met Walt in France.)

In October of 1919, Walt returned home via New York City, his first visit to and exploration of the great city. In two months, he would turn eighteen. While the people we have covered in the American Originals series often had diverse experiences in their early years, none of them exceeded the lengths (literally) that Walt Disney went to in order to “see the world”—and to observe it, to learn.

With no desire to return to work in his father’s jelly factory (which ultimately failed) and no support from Elias for his dreams of becoming a cartoonist, Walt decided to return to Kansas City, rejoining brother Roy. This would be the turning point at which Walt began to earn a living from his drawing and his dreams.

The preceding long history of Walt Disney’s first eighteen years tells us several things about the man, both then and continuing throughout his life. He was tireless, always working and always learning, often in a difficult family environment. Setbacks did not stop him. He was curious about everything, from nature to trains, from travel to business. Above all else, he loved entertaining people; he loved drawing and cartooning. Such was the foundation for the stories that follow.

The Long Progression, Step by Step

The details of Walt’s evolution, and that of his businesses, have filled thousands of pages. Each major Disney achievement is the subject of numerous books. Here we sketch a brief outline of that evolution. Rather than aiming for the moon and dreaming of conquering the world, Walt Disney’s journey was taken one step at a time. While these steps may sound dramatic in hindsight, to Walt each step was the natural progression from the previous one.

The story of Walt Disney and his enterprises is one of continuous improvement, of never being satisfied, of always seeking something new and exciting to try. No matter the risks, Walt was always confident that “things will work out.” Even when few others did, he believed in himself. Equally important, so did Roy.

Stage 1: Making a Living (Almost) from Cartooning in Kansas City

When eighteen-year-old Walt returned to Kansas City, he was sure he could get a job at the top paper, the Kansas City Star. He showed them his sketches of Paris and other work, but they had no openings for a cartoonist. The other paper, the Journal, showed interest, but also had no openings. He finally landed a job at the Pesmin-Rubin commercial art studio for $50 a month.

At Pesmin-Rubin, he drew magazine and catalog ads. Going into the holiday selling season, he was kept busy drawing for department stores, farm implement makers, and many other clients. Posters for movie theaters were also part of his work. At the studio, he met fellow artist Ubbe (later shortened to Ub) Iwerks, son of Dutch immigrants and the same age as Walt. They became fast friends. When the Christmas ads were completed, both young men were laid off.

Walt and Ub then decided to go into business for themselves. They almost called their venture Disney-Iwerks but realized people would think they were caring for eyes, so Iwerks-Disney Commercial Artists was formed. Their revenues were $135 the first month, a great start. Then they saw a help-wanted ad for a company that produced slides and cartoons for movie theaters, to be shown before the feature film. Ub urged Walt to take the job, saying he could continue their little business. Walt took the job. Ub proved a poor salesman, however, and soon the two gave up on the old business and were working together at the Kansas City Film Ad Company.

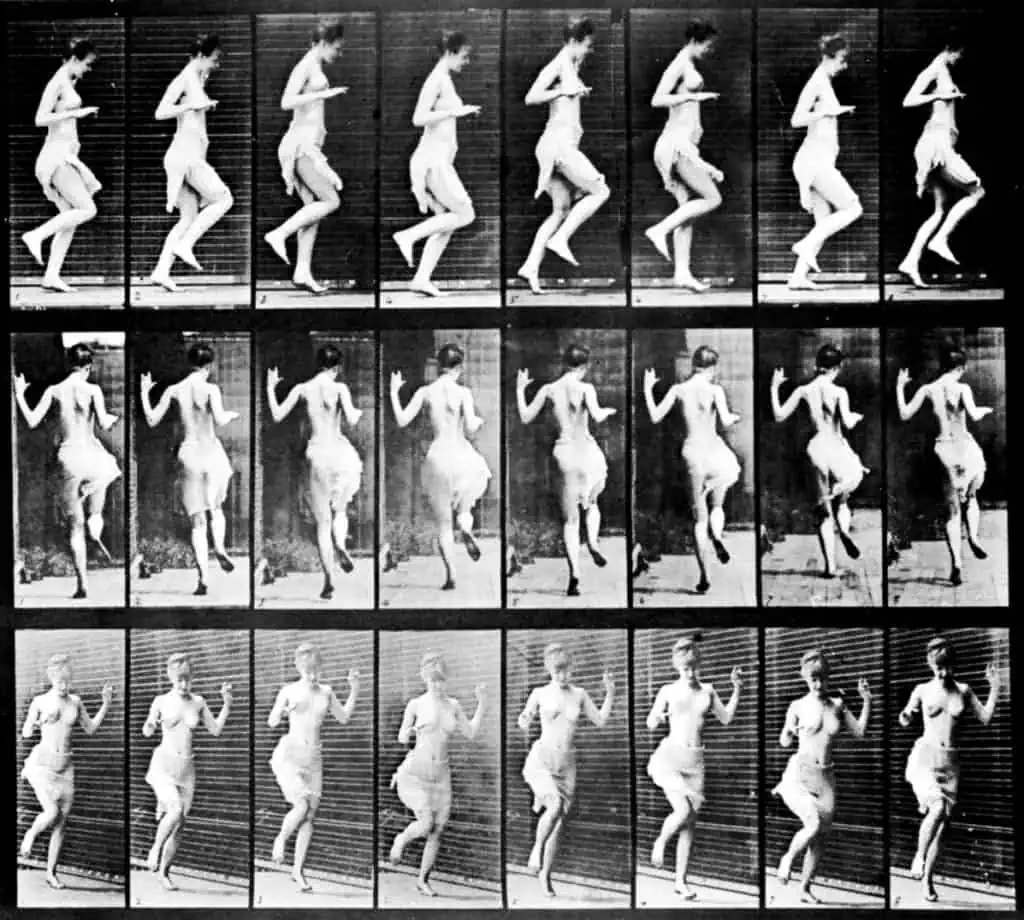

At the Film Ad Company, animations were made by cutting out pieces of paper shaped like arms and legs, pinning them on a sheet, moving them around, and photographing the images after each small movement. Walt, having studied the more natural cartoons coming out of New York animation studios, thought this could be improved. He read several books on how to draw animation, using celluloid rather than the cut-outs. He studied Eadweard Muybridge’s famous photos of animals and humans in motion, copying them at the library and keeping the copies beside his desk. Ub Iwerks was an even better artist than Walt, often taking Walt’s ideas and turning them into cartoons for the big screen. Walt’s pay rose to $60 a week.

Walt’s humorous “gags” were a hit at the local Newman theater chain and were soon named Newman Laugh-O-Grams. Walt tried to convince his bosses at the Film Ad Company to create more of these one-minute shorts to sell to theaters around the nation, to no avail. He started making the films on his own, in addition to working for Kansas City Film Ad. His first longer cartoon, Little Red Riding Hood, can be seen here. Thus began a long tradition of using stories already familiar to the public.

Walt also befriended the cameraman at the company, who usually kept his techniques to himself. Ultimately, Walt bought a camera for $300 and used his spare time and weekends to shoot footage for local theaters. He also shot footage for the national newsreel companies, whose news compilations were shown at theaters across America.

These efforts led to a second try at working on his own. He quit the Film Ad Company. On May 23, 1922, twenty-one-year-old Walt incorporated Laugh-O-Gram Films with $15,000 raised from investors at $250 to $500 each. Soon Walt was joined by Ub Iwerks, five other animators, a secretary, business manager, and “a girl to ink and paint the celluloids.” A New York film distributor sent a $100 deposit check and promised $11,000 in six months for six cartoons but went broke before making the payment.

Walt continued to shoot newsreels, even flying in an early airplane to film aerial acrobatics. He took baby pictures to add to the company’s cash flow. The company still struggled, borrowing another $2,500 to stay in business. Walt often slept in the office, with nowhere else to go after his brother’s house was sold.

Working for a dentist, Walt and Ub produced Tommy Tucker’s Tooth. Walt’s first major technical innovation was presented in Alice’s Wonderland, an amazing eight-minute combination of live action and cartoons that took great skill to create. Many inventions were to follow over the next forty years as Walt never stopped experimenting, trying to create more entertaining products.

Finally, even Walt’s strongest backers, including brother Roy, were unable to advance any more money, and Laugh-O-Gram Films went bankrupt. While many would have given up (and followed his father’s advice to choose a better career), not Walt. He went door-to-door selling baby pictures, then sold his camera, until he had enough money to buy a one-way train ticket to California. In 1923, he arrived in Los Angeles with the clothes on his back, a half-filled suitcase, some drawing materials, and $40 in his pocket.

Stage 2: First Steps in Hollywood

In Los Angeles, Walt lived with his uncle Robert, paying $5 a week for board, money he had to borrow from Roy. He did whatever it took to earn money, including acting as an extra in the movies. Walt applied to become a director at movie studios, with no luck. Roy, by then living in Los Angeles, suggested he give cartoons another try, but Walt was skeptical.

Eventually realizing cartoons were his best shot to get into the movie business, he went to the office of Los Angeles theater owner Alexander Pantages, hoping to sell him on cartoon shorts. Pantages’s secretary told Walt, “Mr. Pantages would not be interested.” A voice from behind a door said, “How do you know I wouldn’t?” Pantages said he would be interested in Walt’s product. Walt set up a cartoon production rig in his uncle’s garage.

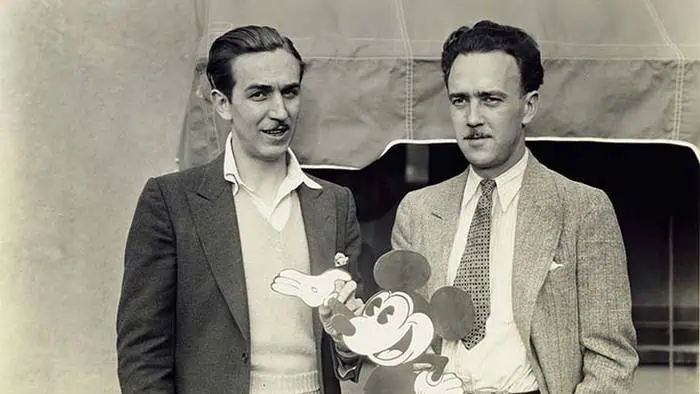

At the same time, he sent Alice’s Wonderland off to a New York distributor, hoping to get a deal. Receiving a positive response, on October 16, 1923, Walt signed a contract with the distributor, MJ Winkler, for six Alice comedies at $1,500 each, followed by six more at $1,800 each. This seemed like a fortune to Walt. Unable to get a loan from a bank on such a risky venture, Roy financed Walt’s efforts and became his partner in the “Disney Brothers Studio,” a fraternal relationship that lasted beyond Walt’s death.

Walt rented a vacant lot in Hollywood for $10 a month, convinced his Alice actress (Virginia Davis) and her family to move from Kansas City to Los Angeles, and began producing the films. He attached a note to the first film he shipped to Winkler, stating, “I sincerely believe I have made a great deal of improvement on this subject in the line of humorous situations and I assure you that I will make it a point to inject as many funny gags and comical situations into future productions as possible.” Successive films in the series often included similar comments. Walt spent more money on each film than on the previous one, straining finances. He was never satisfied.

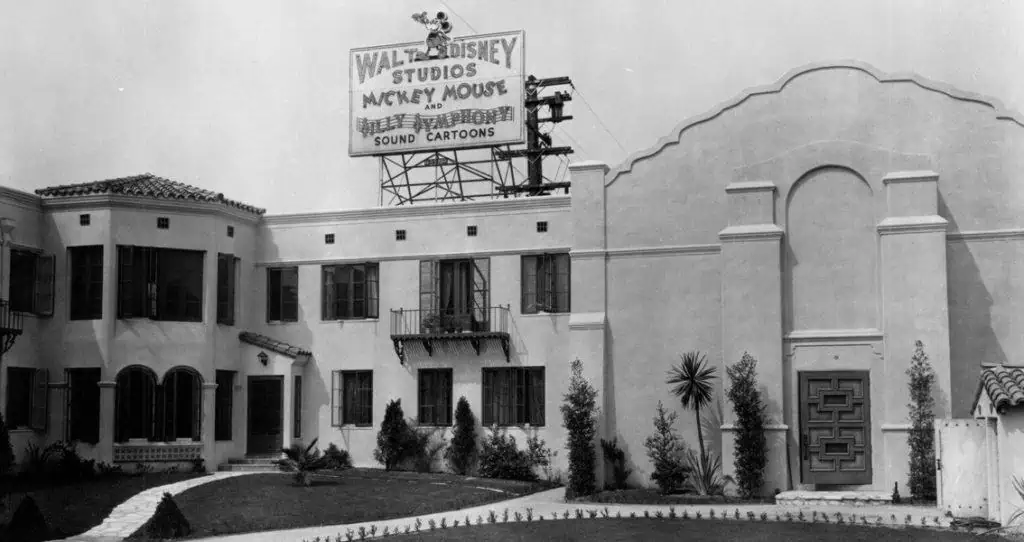

By the spring of 1924, the Alice comedies were showing in theaters. Things were looking up for the twenty-three-year-old entrepreneur and his thirty-one-year-old brother. That summer, Walt convinced Ub Iwerks to join him, moving from Kansas City. In December, their distributor signed up for eighteen more “Alices,” to be distributed to theaters through Universal Studios. More animators moved from Kansas City or were hired locally, including many who went on to fame on their own after working for Walt. In July 1925, the Disney brothers made a $400 down payment on a sixty-by-forty-foot lot on Hyperion Avenue, where they built a new studio in 1926.

Also in July of 1925, Walter Elias Disney married Lillian Bounds, an Idaho-raised woman who worked as an inker and painter in the Disney studios. They remained happily together for forty-one years, until death did them part, when Walt died.

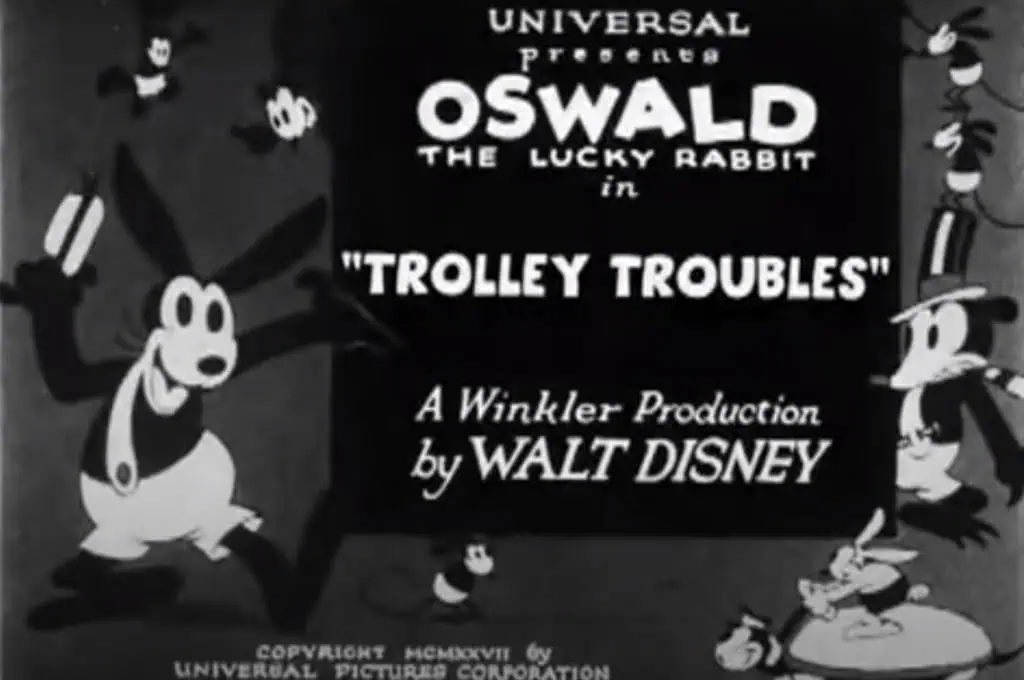

By 1927, the brothers and their staff had produced fifty-six Alice comedies. The series had run its course, and Universal studios asked for a cartoon series using a rabbit. This request led Walt to create Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, his first major effort at an all-cartoon (with no live action) short. The first film released, the delightful Trolley Troubles, was a hit with both theaters and critics. The Disneys bought more land next to their Hyperion studio and hired more people to meet the demand. Walt and Roy built $7,000 prefab houses next door to each other for themselves and their wives.

But Walt soon learned that his distributor was hiring away all of his animators except Ub Iwerks, planning on cutting the Disneys out of the profit stream on Oswald. Universal owned the rights to the popular rabbit. They thought Walt would fail without Oswald. The distributor offered Walt a handsome salary to work for him, but Walt knew he wanted to be independent, to have control over his product. So he turned them down. Walt was then stuck with no rabbit, no money, little staff, and no contract to make more cartoons.

Step 3: The Birth of Mickey Mouse; Struggles and a Breakdown

Stories abound about the birth of Mickey Mouse, but one thing is clear: twenty-six-year-old Walt needed a character to replace Oswald; he needed a character he controlled. So the Mouse was born. The first Mickey Mouse film was 1928’s silent Plane Crazy (the sound was added later), inspired by Charles Lindbergh’s solo flight across the Atlantic. But Walt could not find any distributors to sell it to theaters.

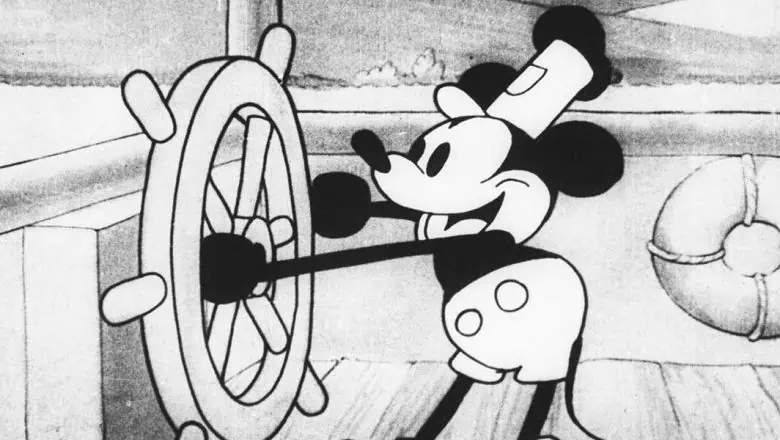

Walt was very interested in adding sound to his cartoons, following the premiere of 1927’s huge sound hit The Jazz Singer, starring Al Jolson. With great experimentation, time, money, and effort, he and his team finally figured it all out, with Walt voicing Mickey. Getting the expensive small orchestra to play in time to the cartoon and perfect the recording was especially difficult. Walt took the film to New York to show distributors, but none were interested. Finally, in desperation, he agreed to let a Broadway theater, which normally staged live plays, show the film, to give the public a chance to evaluate it. The result was Steamboat Willie, the first Mickey Mouse film that the public had a chance to see, which premiered “on Broadway” on November 18, 1928. The public and the critics (even The New York Times) loved it.

Now distributors wanted it, too, but they offered to either hire Walt onto their payroll or buy the complete rights to future Mickey Mouse films. After his experience losing control of Oswald, Walt refused their offers. He finally signed with an independent distributor who wanted to promote his own sound system. Walt went back and added sound to Plane Crazy and did the same with another previously unreleased early Mickey Mouse film, Gallopin’ Gaucho. In ensuing years, Walt and Roy changed distributors several times, often concerned that they were not getting equitable treatment in terms of theater access or receiving a fair share of the profits. They learned to be astute businessmen, with Roy overseeing the company’s finances and continuously borrowing more money.

While Ub Iwerks was still a critical part of the team, he and Walt began to quarrel. Ub insisted on doing all the drawings himself, rather than let a lesser-talented “in-betweener” draw the cels (celluloids) in between key character positions. This slowed down the production of the cartoons and added expense to the process.

Walt’s musical composer, Carl Stallings, suggested they create another series of cartoons in addition to the Mickey Mouse series. His idea was to combine classical and other music with the animation, making the films pure aural and visual delights. The first film of the new Silly Symphony series was The Skeleton Dance, released in July 1929. The company now had multiple successes and was spending $5,000 to make each cartoon.

Walt led every story meeting, developed ideas and gags. When Mickey was angry, Walt chided the artists for having Mickey’s tail down when it should be up, in anger. No detail missed Walt’s eye for story and comedy. From watching audiences in theaters, he had developed a fine-tuned sense for “what worked.”

By 1929, Mickey Mouse had become a national craze, with Mickey Mouse Clubs springing up everywhere. At theaters, audiences would shout, “What? No Mickey Mouse?” if the little character did not appear before the film. While the company should have been profitable, checks from their New York distributor were slow to arrive. When Walt went to meet with the distributor, he was told that he could work for the distributor for a big paycheck ($2,500 per week) and that Ub Iwerks had signed on to leave Walt and work for the distributor. Once again, others were undercutting the Disney brothers and trying to deny them their fair share of the profits.

Walt and Ub signed an agreement in which Ub received $2,920 for his one-fifth ownership of the Disney company. (Years later, Ub returned to work for Walt.)

In 1929, the company was incorporated as Walt Disney Productions. Walt and Lilly owned 60 percent of the company; Roy and his wife, Edna, 40 percent.

Unwilling to work for others, in early 1930, Walt signed a distribution deal with Columbia Pictures under which he retained control and ownership of his product, at a price of $7,000 per cartoon. In 1930, Mickey Mouse comic strips began to appear in newspapers across the country. Nevertheless, the company struggled financially as Walt kept adding staff and spending more on each cartoon to make it better.

Losing Ub, fighting distributors, and money worries got to Walt. He began to lose sleep, to snap at employees, and to go into crying spells. In story meetings, his ever-alert mind sometimes went blank, losing track of the conversation. At the age of thirty, Walt Disney had what was termed “a nervous breakdown.” His doctor ordered him to take a complete rest. In 1931, Walt and wife Lilly took their first vacation in five years, traveling down the Mississippi River, visiting Washington, and then down the East Coast to Key West and Cuba. Returning to Los Angeles via a cruise through the Panama Canal, Walt was in good shape by the time he got back to work at the studio, which Roy had overseen in his absence.

Step 4: New Ideas, Innovations, and Success

By 1931, the Mickey Mouse Club had a million members and Mickey was known around the world. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a fan. Mickey appeared in Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum in London. In 1929, Walt and Roy had accepted $300 from a man who wanted to sell school writing tablets with Mickey on them because they needed the money. Now such licensing deals became a flood, which continue to this day. On toys, the company got a royalty of 2.5 percent on anything selling for under fifty cents; 5 percent on more expensive items.

Ten million Mickey Mouse ice cream cones were produced in 1932. The bankrupt Lionel model train company survived in large part due to the sales of 250,000 Mickey Mouse railcars. In a two-year period, 2.5 million Mickey Mouse watches were sold. Connecticut’s nearly bankrupt Ingersoll-Waterbury watch factory grew from three hundred employees to three thousand to meet the demand.

In many ways, Mickey was Walt. The man carefully guarded the integrity of the mouse, often telling his animators, “Mickey wouldn’t do that.” Walt used his histrionic skills to act out each role and each line of dialog. Studio crews filmed Walt when he voiced Mickey to improve the accuracy of their animations.

Mickey’s success enabled Walt to continue to experiment, to progress in making better entertainments. More staff, more buildings were added at the Hyperion Avenue studios. In July 1932, he released a new Silly Symphony, Flowers and Trees, the first color cartoon. Flowers and Trees became the first animated film to win an Oscar. Walt was thirty-one years old.

Each step in the development of the company required new techniques. Having struggled with visualizing the final product before spending countless hours making drawings, the company developed the idea of the storyboard, pinning preliminary sketches to a four-by-eight-foot fiber board. This and other innovations were copied by others and are used around the world today.

Walt had developed a knack for recognizing talent. While he was a demanding taskmaster, he provided an environment where artists and story writers could do their best work. He also believed in education, as he had proven since childhood. Walt paid employees’ tuition for night classes at Los Angeles’ Chouinard Art Institute, driving them to and from the classes. When he had more money to invest in education, he began holding the classes at the studio, assigning a full-time teacher. The students studied anatomy and human and animal movement, as Walt wanted to inject as much realism into his films as possible.

The year 1933 saw the release of Three Little Pigs, the second Silly Symphony to win an Oscar. The cartoon took character development to a higher level. The tune “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” became a hit and was played by orchestras across the nation, another first for a cartoon. Theaters put the film’s name above the name of the feature film on their marquees. Disney’s distributor and theaters clamored for more “Pigs” films, but Walt responded with his famous remark, “You can’t top pigs with pigs.” He did not like repeating past successes. He did not like sequels: he wanted to keep moving, keep growing.

In the six years since Walt “lost” Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, through 1934, Walt’s crew had grown from six people to 187. They included a dozen “story and gag men,” forty animators with forty-five assistants, thirty inkers and painters, a twenty-four-piece orchestra, and numerous camera, sound, and office workers. Some 150 employees were enrolled in the company’s ever-expanding internal school. Guest lecturers included famous authors and renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright, making it a wonderful experience for the fortunate staff members.

New cartoons and better ways of making them continued to pour forth from the studio. This era saw the introduction of new characters, from Pluto to the ever-popular Donald Duck.

The most important development in 1934, and one of the most important in the history of Walt and the studio, was the idea of producing a feature-length cartoon. Walt thought it might cost $500,000, terrifying Roy (who had to raise the money) and even concerning the usually supportive Lilly. One evening, when the animators returned to the studio after dinner, Walt called them into the sound stage, saying, “I’ve got something to tell you.” He proceeded to lay out the story of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, a project that was to consume Walt and almost consume the studio.

Producing short after short while working away on character development for Snow White, Walt again approached burnout. So he, Roy, and their wives took an extended trip to Europe, his first return since the war. Their trip was interrupted by the press seeking the now world-famous Walt and by visits to royalty and heads of state, including Italy’s Mussolini. Still, Walt remembered every nook and cranny of the cities, giving driving directions to taxi drivers in Paris and London. Everywhere he went, Walt walked the streets, talked to shopkeepers, and kept learning, learning.

Once back in California, Walt focused on Snow White, years in the making, with an ever-increasing budget. He acted out every scene. He obsessed on the soundtrack. Having seen many musicals, he felt they often “just burst into song” without fitting into the story. He wanted the music to match the story at every point. He had a wire run from the soundstage to his office, so he could continually listen to what was being recorded.

In 1936, Walt attended a famous annual gathering of the powerful at the Bohemian Grove in Northern California. Leaders of business and government camped out in a serene forest. But Walt could not sleep due to the roar of awful snoring, and this gave him ideas for sounds for Snow White’s dwarfs. No idea or detail was too small for Walt to absorb and incorporate into his work.

The life of a true innovator is rarely easy. Selling the world on the idea of a feature-length cartoon was extremely difficult. Disney’s distributor expressed zero enthusiasm for the project. Industry people called it “Disney’s folly.” Even one of his employees wrote an anonymous note to him, “Stick to shorts,” galling Walt. As the years, experimentation, and cels flew by, the cost rose to $1.5 million, triple what Walt had estimated. The bankers refused to loan more money on the project, threatening the company’s existence. Ultimately, Roy convinced a reluctant Walt to show their banker some preliminary sketches. The banker responded with, “That thing is going to make a hatful of money,” and loaned them the needed funds.

On December 21, 1937, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs premiered in Los Angeles. The premiere was attended by “everyone who was anyone.” Some cried when Snow White went into her deathlike sleep. At the end of the film, the audience stood and cheered. The film generated two more hit songs, “Heigh Ho, It’s Off to Work We Go,” and “Whistle While You Work.” All attendance records were broken in an unprecedented three-week run at the nation’s largest theater, New York’s Radio City Music Hall. In its first of many releases, Snow White generated $8 million in box office revenues, when the average ticket price was just thirty-eight cents. Adjusted for inflation, the film is still the highest grossing animated film of all time at over $1 billion, among the highest figures for any type of film. Walt’s grasp of what the public would like had once again been vindicated.

Money poured into the company. Walt had previously established a bonus system, but Snow White made those checks much bigger. As hard as he worked his employees (and as rarely as he complimented them), Walt appreciated their efforts.

At the same time, he came to realize that the company had a “brand,” a name that stood for something in the eyes of the public. And that brand was Walt Disney. While a few workers resented him getting so much of the credit, the vast majority loved the opportunity they were given to participate in producing quality, innovative films. Walt once told a new employee, “There’s just one thing we’re selling here, and that’s the name Walt Disney.” Walt Disney Productions was at the time tiny compared to the big studios: Paramount, MGM, Warner Brothers, and Fox. Yet none of them ever developed a true brand; their pictures varied in quality and audience appeal. You never knew exactly what to expect. Consumers came to know what they’d get when they saw the Walt Disney signature, a tradition that continues to this day.

Also in 1937, the studio released The Old Mill, the first Silly Symphony using a Disney invention: the multiplane camera. By laying out cels one above another, spaced several inches apart, a better illusion of depth was created. This camera is considered one of the most important technical inventions to come out of the Disney studios in this period.

Walt’s understanding of the future was also indicated by his refusal to give his distributor the television rights to his cartoons, a decade before commercial television became a reality.

Despite all his energy, Walt had a shy streak. He did not enjoy speeches and public appearances. He and Lilly did not participate in the Hollywood party scene. Walt spent his free time with their two daughters, Diane (born in 1933) and Sharon (1936). When Snow White won an honorary Oscar, Shirley Temple presented it to the sweat-covered Walt, saying, “Don’t be nervous, Mr. Disney!” The Oscar was accompanied by seven dwarf Oscars.

Step 5: Risks, Struggles, Setbacks

With this success, Walt lost interest in the short animations, though the studio continued to produce them. He had “been there, done that.” He now focused on feature-length animations, adding new facilities for their production.

In 1940, the company, now with a thousand employees, moved into large new facilities in Burbank, costing $3 million. Designed as a “worker’s paradise,” the buildings were carefully set up to be a “factory” for producing animated films. Walt loved the planning process. He figured out every detail, even custom designing the best chairs for animators. He went so far as to bring in an experienced, eighty-year-old carpenter to oversee the other carpenters: his father, Elias.

Every time his company became prosperous and he and Roy could sleep well, with money in the bank, Walt would find new ways to spend money to make better pictures, landing them back into debt. Animation was (and is) a painstaking process, cel by cel. The costs were often far greater than making a live action picture of the same length.

As a result, Walt Disney Productions sold preferred stock to the public in 1940, beginning trading on the stock exchange. The transaction infused a badly needed $3.5 million into the company’s coffers. Walt and Roy retained voting control of the company.

Despite his efforts to create a great working environment, about three hundred of his employees went on strike in 1941. While quickly resolved, the experience disturbed Walt and may have led him to become a bit more personally distant. He later admitted that he missed the days when he had only a handful of close associates.

Walt used the multiplane camera and expensive special effects on his next feature, Pinocchio, released in February 1940. Despite carrying the hit song, “When You Wish Upon a Star,” the film did not cover its $2.6 million cost, almost double what Snow White had cost.

Pleased with the response to the music-filled Silly Symphony series, Walt decided to try a feature-length all-music film. The result was Fantasia, released in November 1940. Walt worked with famous Philadelphia Orchestra conductor Leopold Stokowski and hired a full orchestra, using classical music for each scene. Mickey Mouse as the sorcerer’s apprentice became famous over the years. But the film took over twenty years of re-releases to break even and recoup the $2.3 million investment. In retrospect, it is considered a classic film.

August of 1942 witnessed the release of Bambi. More serious in tone than the studio’s prior films, Bambi also brought new challenges. Walt wanted the all-animal feature to be as lifelike as possible. He sent a cameraman to Maine to film thousands of feet of film of life in the forests. He brought two deer and a host of other animals to the studio, where he created a small zoo for the artists to study. He brought in artists experienced in painting animal scenes to teach classes at the studio school. Again, no detail was left unexamined.

As hard as he tried to push, the creation of Bambi was time-consuming and thus expensive. Experienced artists could draw a cel of the fawn in forty-five minutes; newcomers took ninety. Daily output crept to eight drawings per artist per day, six inches of film, compared with prior averages of ten feet per day. Like Pinocchio and Fantasia, Bambi did not recover its costs in its first run at the box office, again straining the studio’s finances. One of the few money-makers during this period was 1941’s Dumbo, made inexpensively for $600,000. The studio had not had a major hit since Snow White.

World War II brought both challenges and opportunities. On the income side, foreign markets, which had represented 45 percent of the company’s revenue, dried up. Royalties due them from overseas were frozen in bank accounts due to the war. On the other side, the government came to Walt and his team to produce propaganda and other war films. The company rose to the challenge.

Needless to say, the Disney films were effective. Adolph Hitler was particularly galled when Donald Duck appeared in Der Fuehrer’s Face. (Note that Walt’s short animation competition in Hollywood also turned out films for the war effort, as exemplified by Warner Brothers’ Looney Tunes film The Ducktators, with music by former Disney employee Carl Stallings.)

Walt became interested in the work of Major Alexander de Seversky, a Russian aviator who had commanded squadrons in the First World War and invented bombsights and navigation controls. De Seversky was an advocate for using air power to win the war and had written a book, Victory Through Air Power. Walt made a film of the same title (at a $400,000 loss) and tried to get it screened at the White House for President Roosevelt, who had been a navy man. But an admiral who wanted the bulk of military spending for the navy prevented the president from seeing it. Reportedly, Winston Churchill later asked FDR if he had seen the film, which he had not. A copy was flown to their meeting in a fighter aircraft; after FDR watched it, the US invested more in air power, helping to win the war.

To meet the demand for war films, everyone at the studio worked six days and two nights a week. Prior to the war, Walt Disney Productions had produced about thirty thousand feet of film a year. During the war, this rose to three hundred thousand feet each year. The company had offered to donate the films to the war effort at cost, but government bookkeepers wrangled with Walt over every penny of expense, while Walt focused on making great films, spending what he felt was required.

Between the weak results of his new feature films and the profitless war films, the early 1940s were not good financially for the company. Borrowings from the Bank of America rose to $4 million, and the bank was nervous. Their banker asked Roy and Walt to meet with the bank’s board of directors in San Francisco. The bank’s founder and chairman, A.P. Giannini, in his mid-seventies, never took a seat, strolling around the room as the grim-faced bankers grilled Roy and Walt. At last, Giannini spoke. He asked his board members how many had seen Walt’s movies. Several had seen none.

“Well, I’ve seen them. I’ve been watching the Disney’s pictures quite closely, because I knew we were lending them money far beyond the financial risk . . . . [The pictures] are good this year, they’re good next year, and they’re good the year after . . . . You have to relax and give them time to market their product.” The smart old man stood behind the creative wizard; the bankers kept loaning money to Walt and Roy.

Step 6: Post-War Successes, Diversifying the Business

These financial challenges may have cost Walt some sleepless nights, but it never stopped him from dreaming, from moving on to the next challenge. But it was never easy. Even Roy challenged him. Walt wanted to move ahead on two feature-length animated films on which he had started working before the war, Alice in Wonderland (finally released in 1951) and Peter Pan (1953). Roy told him he was nuts and stormed out of the office. Neither brother slept that night; they made up the next morning.

In seeking the next challenge, Walt turned to live-action films. He later said, “I knew I must diversify. Knew the diversifying of the business would be the salvation of it. I tried that in the beginning, because I didn’t want to be stuck with the Mouse. So I went into the Silly Symphonies. It did work out. The Symphonies led to the features; without the work I did on the Symphonies, I’d never have been prepared even to tackle Snow White. A lot of the things I did in the Symphonies led to what I did in Fantasia. I took care of talents I couldn’t use any other way. Now I wanted to go beyond even that; I wanted to go beyond the cartoon. Because the cartoon had narrowed itself down. I could make them either seven or eight minutes long—or eighty minutes long. I tried the package things, where I put five or six together to make an eighty-minute feature. Now I needed to diversify further, and that meant live action.”

Returning to the hybrid techniques of the old Alice comedies, but vastly improved, Walt and his people created Song of the South (1946), which was 70 percent live action and 30 percent cartoon. The film made a modest profit of $200,000 on an investment of $2 million. The 1950’s Treasure Island was the company’s first all live-action feature and less expensive to make. Walt followed this up with an additional sixty-two live-action features over the next sixteen years.

The film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, released in 1954, was not one of those less expensive films. Due to the costs of building a huge 4,000-pound squid and a 165-foot-long tank for underwater scenes, the film cost over $4 million. In order to convince his bankers to loan more money, Walt successfully showed them early clips from the film, which turned into a huge success.

In 1955, Lady and the Tramp, the first animated film presented in widescreen CinemaScope, premiered. This was also something of an innovation for the studio: it was not based on a traditional story that the public already knew. This gave Walt and his storytellers the chance to develop totally new characters, a process he enjoyed.

The company also began making nature films, starting with The Living Desert in 1953. Since their distributor did not believe in the film, Roy created a small distribution division, Buena Vista. The Living Desert made a profit of $4 million on a cost of just $300,000, proportionately one of the most profitable films the company ever made. Walt then spent substantial effort and sums sending cameramen around the globe for this successful series.

These films began to make money. Even Pinocchio and Bambi became highly profitable in periodic re-releases, a system that Disney established. Given the Disney brother’s contentious history with their distributors, they took a chance on distributing all of their own pictures, including 20,000 Leagues. This was a very disruptive and risky move in the traditional system of how movies moved from studios to theaters. Over time, Buena Vista became one of the largest and most successful of the film distribution companies.

Also worth noting is that Howard Hughes, owner of the struggling but still large RKO studio, offered to give it to the Disneys, along with a $10 million line-of-credit which would have solved all their money worries. But the Disney brothers turned him down, not wanting to take on RKO’s problems. Walt’s fertile imagination was enough to keep them busy.

These successes of the early 1950s led Walt to dream even bigger.

Step 7: From the Big Screen to the Small Screen and the Theme Park

Walt often took daughters Diane and Sharon to amusement parks. But he was disturbed by the slovenly and unfriendly staff and the filthy conditions. Why couldn’t there be a clean place, a nice place, to take a family? With his keen understanding of family entertainment, he began to think about the idea. What evolved was almost a walk-through version of what he had previously put on the big screen. (It is interesting to note that Walt always turned down any suggestion that he make films for children. His goal was to make things for the whole family, things that “brought out the child in every adult.”)

As always, Walt’s curiosity led him everywhere. He studied amusement parks and shopping malls across America. Walt visited the National Parks and every circus, zoo, carnival, state fair, and county fair that he could. He watched people—how they moved, whether they smiled or not. What was their total experience like? He ventured abroad. The only amusement park he found up to his standards of cleanliness was Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen.

Over time, Walt’s vision for an amusement park became more real and more expensive. He overcame resistance from everyone around him. What was to become Disneyland became an obsession with Walt. He sold his second home in Palm Springs and borrowed $100,000 to start a new company (later merged with the studio) to build the park. Like everything he touched, Walt never stopped believing in himself and what his studio could accomplish.

At the same time, television was rising rapidly. In 1945, there were fewer than ten thousand televisions in American homes and businesses. By 1950, this figure had soared to around 6 million; by 1960 more than 60 million televisions had been sold. The two big networks, NBC and CBS, were eager to bring the Walt Disney name into people’s homes. Most Hollywood moguls resisted television, seeing it as competition. They would not let a TV set appear in a movie and banned their actors from appearing on television. Theater owners said they would not show movies from any studio that allowed its movies to appear on television.

But Walt saw a big opportunity. He was tired of relying on distributors and theater owners to judge his product. He was tired of critics. He was only interested in what his ultimate viewers thought. He said, “Television is going to be my way of going direct to the public, bypassing the others who can sit there and be the judge on the bench.” In fact, he believed that if people liked what they saw on television, they’d want to see more in the theaters. As long as he produced a quality product, he knew the public would be loyal.

Walt also saw television as a chance to fund his amusement park dream. Roy traveled to New York and told the networks that they would provide TV programming if the rich networks would help finance the park. NBC’s chief and founder David Sarnoff expressed some interest, but negotiations bogged down when it came down to specifics. Frustrated, Roy called up the head of the much smaller, struggling ABC network, Leonard Goldenson, who answered, “Where are you? I will be right over.” When the dust settled, the Disney brothers had agreed to a weekly program on ABC, and ABC had agreed to provide a $4.5 million bank loan to finance Disneyland. ABC also invested $500,000 for a 35 percent ownership in the company Walt had set up to build the park. (Five years later, ABC sold that interest back to Disney for $7.5 million, a nice return on a risky venture.)

After a great deal of research for the best location and a study of future freeway routes, booming Anaheim, California, was selected as the site for Disneyland.

On October 27, 1954, the Disneyland television program premiered on ABC. Despite his shyness, Walt introduced each show, further building the Walt Disney brand. The first episode was, in effect, a commercial for Walt’s forthcoming amusement park. In December, another episode told the “behind the scenes” story of the making of 20,000 Leagues. While it might have been a long trailer for a movie, it was so well-made and entertaining that it won an Emmy as the best show of the year.

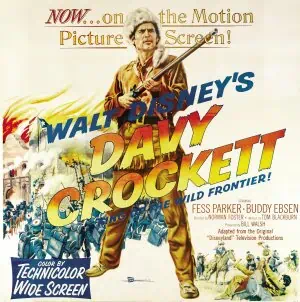

The big hit of the first season of Disneyland, the TV show, was Davy Crockett, which first appeared in December 1954. The theme song, “The Ballad of Davy Crockett” was the number one song on Hit Parade for thirteen weeks, selling ten million records. Fess Parker played Davy and became a major star. Davy Crockett coonskin hats became all the rage: more than ten million were sold, driving the wholesale price of skins from fifty cents a dozen to five dollars. Costumes, coloring books, and toys of every kind poured forth. Walt Disney and his studio had created another national sensation. Walt’s prediction that television would help movies was proven out when the movie version of Davy Crockett, which cost $700,000 to make, made a $2.5 million profit on “something ninety million people had already seen for free.”

Disneyland quickly became the most-watched show on television. It made ABC a meaningful contender against NBC and CBS.

In the meanwhile, the planning and building of the Disneyland park moved ahead. Walt was obsessed, saying, “The park means a lot to me. It’s something that will never be finished, something I can keep developing, keep ‘plussing’ and adding to. It’s alive . . . . When you wrap up a picture and turn it over to Technicolor, you’re through. Snow White is a dead issue with me. It’s gone. I can’t touch it. There are things in it I don’t like, but I can’t do anything about it. I want something live, something that would grow.”

Walt described the park this way: “The idea of Disneyland is a simple one. It will be a place for people to find happiness and knowledge . . . a place for parents and children to share pleasant times . . . for teachers and pupils to discover greater ways of understanding and education . . . the older generation can recapture the nostalgia of days gone by, and the younger generation can savor the challenge of the future. Disneyland will be based upon and dedicated to the ideals, the dreams and hard facts that have created America . . . and send them forth as a source of courage and inspiration to all the world. Disneyland will be something of a fair, an exhibition, a playground, a community center, a museum of living facts, and a showplace of beauty and magic. It will be filled with the accomplishments, the joys and hopes of the world we live in. And it will remind us and show us how to make those wonders part of our own lives.”

When Walt’s board of directors resisted the park, he showed them his plans; tears welled in his eyes.

In short, nothing Walt had previously created reflected the man, his heart and soul, to the extent that Disneyland did.

As usual, Walt was into the details. He went to Southern California’s top tourist attraction, Knott’s Berry Farm, and observed the visitors. Where did they go, and in what order? How wide were the walkways? When the people had to wait in line, they grew frustrated, leading Walt to make sure his customers had something to watch, even while waiting in line. When his colleagues worried about vandalism to their expensive exhibits and rides, Walt said that if they kept the park spotlessly clean, the public would see that and respect the place. “Appeal to the best in people,” Walt said. He made sure every trash can was custom designed to match the theme of each area.

When other park owners told him he had to have multiple entrances, Walt would not budge from his idea of only one entrance. This was not going to be an ordinary park; this was going to be a show, with a clear introduction, a grand entrance. Walt had a berm built around the park so that no outside distractions would divert people’s eyes. He made his architects work overtime to create the right visuals. Every building appeared taller than it was by reducing the scale of the upper stories. Walt studied every sight line, moving trees around to perfect his vision. He rode every ride over and over. He squatted down to the ground to see the same views that small children would see.

Walt told his designers, “I want them (the visitors), when they leave, to have smiles on their faces. Just remember that; it’s all I ask of you as a designer.”

Walt went against the advice of every other amusement park owner when he created large public spaces and plenty of casual seating and meeting places, which the experts saw as an expensive waste of space. Walt Disney walked in his customers’ shoes to a degree that few businesspeople do.

As opening day approached, Walt told his managers that they did not need a fancy administration building. “I don’t want you sitting behind desks. I want you out in the park.” He had an apartment above the firehouse so he could visit often and observe customers. Once the park opened, he took his family there every Saturday, always learning, always talking to workers and customers, forever tweaking and improving. Disneyland was, indeed, a living thing.

It goes without saying that Disneyland was a success from the instant it opened on July 17, 1955. Walt’s experts had predicted two to three million visitors in the first fifty-two weeks of operation, but one million came in the first seven weeks. In the first year, attendance beat projections by fifty percent and average spending per visitor was 30 percent higher than anticipated. In the first four years, fifteen million people came. Disneyland was a home run. And highly profitable.

The Final Step

In the following years, Walt and the company had success after success. The Mickey Mouse Club premiered on ABC, five days a week, on October 3, 1955. In developing this idea, Walt had carefully studied the behavior of children at recess. ABC sold $15 million worth of advertising in the first year (equal to $150 million in 2020). An astounding 75 percent of American households tuned in. Each day, American retailers sold twenty-four thousand mouse ear caps.

In 1961, Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color premiered on NBC, along with parent company RCA, the leader in color television. As demonstrated in his films, Walt had always believed in color. In fact, he had recorded all his shows for black-and-white TV in color, so they’d be ready to rebroadcast when color came along. To call Walt Disney a visionary would be an understatement.

At the same time that the company succeeded on television and at Disneyland, new movies kept coming. Old Yeller (1957), The Shaggy Dog (1959), and many other hits came along. The company continued to innovate: One Hundred and One Dalmatians in 1961 was the first animated film to use the Xerox process for drawings. The year 1964 witnessed the premiere of Mary Poppins, again combining animation with live action. The movie was one of the company’s greatest commercial and critical triumphs. Mary Poppins is one of the few films about which another movie (Saving Mr. Banks) was made, starring Tom Hanks as Walt Disney.

Disneyland continued to be a living, breathing thing for Walt. Major new attractions were continually added. With great experimentation and effort, “animatronics” were added, allowing characters to speak, to seem more human. He made those working on the project watch TV without sound, so they would see how people’s mouths moved. Others said they could tell who was working on the animatronics project because they never looked you in the eyes; they just watched your mouth. (In contrast, Walt was famous for making eye contact, scolding anyone who did not look back with their eyes. By looking into their eyes, Walt could tell what people were really thinking.)

But one thing that bugged Walt was the proliferation of cheap motels and unsightly parasite businesses all around the park. He wished he had bought more land.

Walt was always very focused on the future. He believed that future was best developed and best predicted by science and by the great corporations of America. (Based on his experiences in both World Wars, he had a distrust of the effectiveness and efficiency of government.) Walt began to spend time visiting the laboratories of big companies like Westinghouse Electric, Ford, and General Electric, asking what they were up to. When he had the chance to design exhibits for the New York World’s Fair of 1964–65, he leapt at the opportunity. He knew he would learn things that could be used in Disneyland and that he could experiment with new ideas. Designed by Walt’s people, Pepsi’s “It’s a Small World” ride and the state of Illinois’s “Abraham Lincoln Animatronic” were among the hits of the fair. After the fair, Walt moved several exhibits to Disneyland.

The success of Disneyland, the experience of working on the fair, and Walt’s unending ambition led to what is in hindsight obvious: Walt Disney World, near Orlando, Florida. While Disneyland was a bold move for a company the size of Walt Disney Productions, Walt Disney World was truly a “bet the company” idea. As was true throughout his life, money meant nothing to Walt except what you could accomplish with it, and how you could use it to make life better and happier for others.

The massive project required the acquisition of thousands of acres of land, the creation of a new city with its own fire and police departments, and the investment of hundreds of millions of dollars. Walt was totally engaged in the process, with his usual attention to detail. He even dreamed up an ideal city where people could live in a cleaner, better environment. While this vision was never fully realized, EPCOT, which opened in 1982, has served to replace the great World’s Fairs which have declined in popularity.

But Walt Disney, a lifelong chain smoker, died at the age of sixty-five on December 15, 1966, and never saw the opening of Walt Disney World.

Brother Roy, eight years older, saw the project through to completion, opening in October 1971. The seventy-eight-year-old had wanted to retire several years before, but Walt kept him engaged as they moved from one project to the next. With Walt Disney World open, Roy finally was ready to relax, hoping to cut his workload in half and take a long vacation. He never got the chance. On December 20, 1971, Roy Disney died of a cerebral hemorrhage.

These two men, among the most unique “management teams” in American business history, both worked until the day they died. And loved every minute of it.

Disney since Disney

Over the following years, the Walt Disney Company has seen ups and downs, management conflict, and controversy. Some leaders have been brilliant; some less so. In 1996, the company bought ABC and along with it the Capital Cities Broadcasting TV chain and ESPN. With that acquisition, the company gained a talented young executive named Bob Iger. Leading the Disney company from 2005 to 2020, Iger took it to new heights. Today the company operates theme parks around the world and owns the powerful Pixar, Star Wars, Marvel, Fox, and other movie brands.

When Walt Disney died, his company had just crossed the $100 million annual revenues mark. It would not have ranked among the Fortune 500 companies at that time. As of 2020, it is the largest and most valuable content-creation company in the world, with annual revenues of about $70 billion and a stock market valuation in excess of over $200 billion. The theme parks draw 150 million people a year, 427,000 a day, over one-third of them at Walt Disney World, one of the largest single business operations on earth. “Parks, Experiences, and Products” generate the most revenue of any part of the company and make annual operating profits exceeding $6 billion. One man’s ambition has come a long way!

What Can We Learn from the Life of Walt Disney?

Walt Disney’s life story provides an endless list of adjectives to apply to the man. Many are familiar to nearly every story of entrepreneurial success: hard work, persistence, overcoming obstacles, ignoring naysayers, innovation and experimentation, and driving his associates to achieve more than they ever dreamed they could.

But there is another layer to Walt. His absolute obsession on every detail, his driven curiosity about people and what they liked, and his ability to put himself in the shoes of his beloved public were exceptional. Walt Disney had an overwhelming desire to serve others, to make them laugh and smile. He achieved that to a greater degree than any human who has ever lived. To the extent that those values remain intact at the Walt Disney Company, its future success is assured. But even if it were to see hard times, it has Snow White and other great works of “entertainment” in the vault to fall back on.

In concluding this man’s story, we cannot help but return to some of the issues raised in the first paragraphs of this article. Was Walt Disney an evil or bizarre man? No, every indication is that he was a committed family man with simple values. Was he a unique genius or artist, another Da Vinci? Our answer would again be no; he was just a man who paid attention to details and to what the public wanted. He only wanted to entertain.

When considering this man in full, our assessment is that Walt Disney was, like all of us, an imperfect human being. Above all else, he was among the most normal of Americans, sharing their histories, their biases, their dreams, and their ambitions. Everything he achieved reflected his roots in the Midwest, both rural and urban. There is nothing in his story that could not be achieved by the next generation of American Originals, especially if they have an exceptional, supportive partner with different skills—perhaps even a brother like Roy.

Gary Hoover

Sources: As mentioned at the start of this article, there are thousands of books about Walt Disney, his films, the theme parks, and his companies. Often these books disagree on details and stories. We have opted to accept the facts as described in Walt Disney: An American Original, by Bob Thomas (1976), one of the most popular of the many biographies of Walt. The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life (1997), by Steven Watts, and Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (2006), by Neal Gabler, are comprehensive “balanced biographies.” The Gabler book, the longest and most detailed of them all, has been especially popular, though Walt’s daughter Diane took great exception to some of Gabler’s conclusions about her father and his personality. Yet another biography is The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, by Michael Barrier (2007). Each of these books dug deep into company archives and conversations with those who knew Walt, but only Bob Thomas actually knew the man. On the negative side, Disney’s World: A Biography by Leonard Mosley (1985) and especially Walt Disney: Hollywood’s Dark Prince (1993) should be avoided if you are interested in reality. The first biography of Walt published in 1959, The Story of Walt Disney, by his daughter Diane Disney Miller, “as told to Pete Martin” (who wrote most of the book), is obviously one-sided, but contains many insights into the man from one who knew him well. Building a Company: Roy O. Disney and the Creation of an Entertainment Empire, also by Bob Thomas (1998), is a much-deserved biography of Roy. In researching this article, we found Walt Disney: A Bio-Bibliography, by Kathy Jackson (1993), extremely helpful, with complete lists of every film and a very useful chronology. Among the thousands of other books about Walt and his projects, we especially enjoyed Walt’s Revolution! By the Numbers by Harrison “Buzz” Price (2004), by the consultant who selected the Anaheim site for Disneyland and worked closely with Walt for years. For histories of each film and the parks, we suggest a search of any online bookselling sight. There are also many video collections available on those sites.

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.