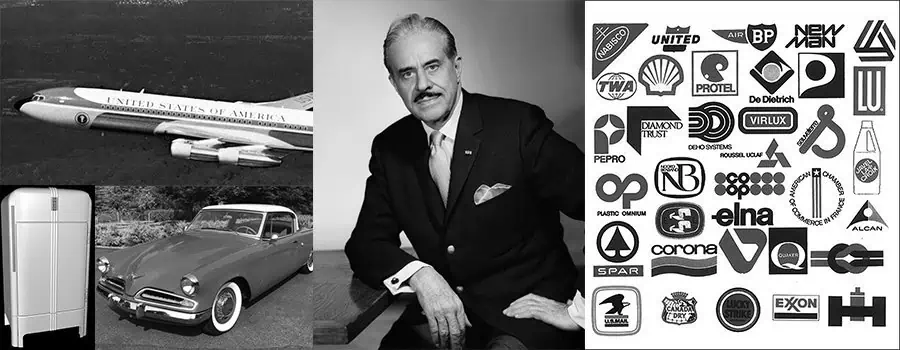

Outside of the field of product and transportation design, too few people know who Raymond Loewy was. The best-known industrial designer, founder of the industrial design profession, and member of the pantheon of our greatest designers, it is time for wider recognition of this amazing man. Coming to the United States from France in 1919 at the age of twenty-five with $40 in his pocket, Loewy brought with him a love of trains, cars, and good design, but he soon also developed a love of America. He was featured in Fortune and Life magazines and made the cover of Time. Forty years ago, he was engagingly interviewed on TV’s 60 Minutes. Called “the frog” and “a refrigerator designer” by leaders of the auto industry, he created some of the most visionary automobiles in American history. He trained and developed dozens of other top designers. Today we see his work every time we see Air Force One, the Shell Oil or Exxon logos, or the Greyhound dog on a bus. Over his sixty-year career, he reshaped the world as we know it. This is his story.

Beginnings

Born in Paris on November 5, 1893, Raymond Loewy was middle class and educated, the son of a Jewish father and Catholic mother. His father’s job as a business journalist introduced Raymond to writing and world affairs. As a teen, he published a newspaper for his neighborhood—the first sign of his entrepreneurial bent. The boy soon showed a love of art, constantly drawing locomotives and automobiles. His mother took him to railroad roundhouses to watch the action, which he loved. At fifteen, he patented his design of a model airplane. Developing skill at selling his ideas and making presentations, he started a company to sell the planes, but soon sold it. He built speedboat models that won acclaim. And he earned a degree in engineering at the University of Paris.

Then World War I came to Europe. Loewy served four years and two months on the front, earning decorations for combat bravery three times. By the war’s end, both his parents had died of the Spanish flu, which killed millions. They left little inheritance. His two older brothers had moved to the United States and become successful in banking and medicine. In 1919, he followed them, sailing to New York on the SS France with one set of clothes—his army uniform—and $40 that his brother had loaned him. As he crossed the Atlantic, he drew sketches of parts of the ship and of other passengers.

The American

Loewy hoped to apply his education and get a job as an electrical engineer at General Electric. Meeting his brothers’ friends, he was introduced to the head of Macy’s. He accepted a job to dress one of Macy’s main store windows. Rather than the ornate, cluttered look then in vogue, he used just one mannequin, one spotlight, and a mink stole at the foot of the mannequin. Pure simplicity. When he came to work the next day, he sensed the dismay of his co-workers and resigned before they could fire him.

Loewy’s shipboard sketches, however, had drawn the attention of fellow passengers, leading him to meet magazine editors and advertising men. He sensed the opportunity to make money as an independent sketch artist. Soon he was doing work on print advertising for Wanamaker’s Department Store, the Butterick Pattern Company, the White Star shipping line, and Pierce-Arrow motorcars. He even designed costumes for the great Broadway showman Flo Ziegfeld.

He used his European roots to his advantage, separating him from the competition. He wrote his brother that, soon after landing, he was getting $75 each for sketches he whipped out in an hour, even while speaking no English. In 1924, Harper’s Bazaar magazine became his most lucrative account, and the fashion editor took him under her wing, introducing the thirty-year-old Loewy to New York’s elite. He made the most of his new contacts. By 1927, he was designing uniforms for Saks Fifth Avenue’s elevator operators and illustrating many of the store’s print ads.

Nevertheless, Loewy was “successful . . . but intellectually frustrated,” he later told the New York Times. Working with the big department stores, he saw the expanding flow of new products and consumer conveniences as the urban middle class grew. He said, “Prosperity was at its peak, but America was turning out mountains of ugly, sleazy junk. I was offended my adopted country was swamping the world with so much junk.” Despite making $30–40,000 per year as an illustrator ($400–600,000 in today’s money), he wanted to have a greater impact.

The Industrial Designer

Loewy later wrote, “The country was flooded with refrigerators on spindly legs, and others topped by towering tanks. Typewriters were enormous and sinister looking. Carpet sweepers when stored away took up the greater part of a closet, and telephones looked (this is no pun) disconnected. I felt that the smart manufacturer who would build a well-designed product at a competitive price would have a clear advantage over the rest of the field when things would become tough. . . . Competition would become fierce, good design would help sales, manufacturers could be convinced—and I was the one to do the job, both the designing and the convincing.”

So Raymond Loewy “hit the road” with a business card reading, “Between two products equal in price, function and quality, the better looking will outsell the other.” Traveling from one manufacturing company to the next in the industrial Midwest, his Frenchness did not provide the “chic” boost that it had in New York. He spent hours in waiting rooms and rode train after train: to Akron, Chicago, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Toledo, and “points west.” Rejection after rejection, he kept calling, kept begging industrial leaders to see his vision of a better-looking world. He said, “No one in the manufacturing world had ever heard of industrial design, and no one was interested. My life was a dreary chain of calls on bored listeners.” But Raymond Loewy was not the kind of man to give up on his visions and dreams.

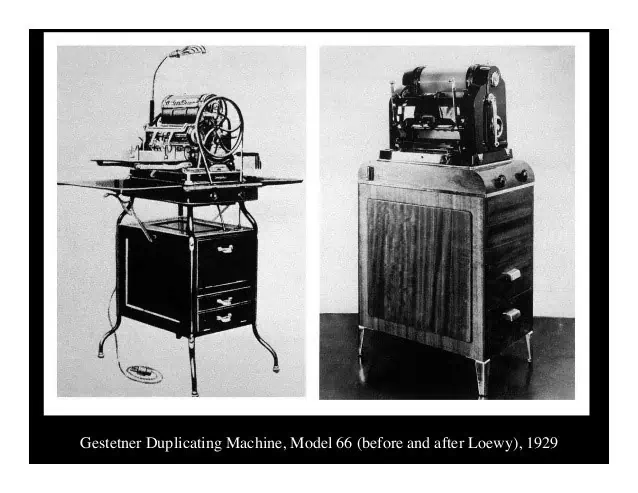

Working with the big ad agency Foote, Cone, and Belding, Loewy was sent to London in 1929 on an account. Sitting in the waiting room of the ad agency, he talked about how London taxis could be better designed. Overhearing the conversation, British and American duplicating machine manufacturer Sigmund Gestetner asked Loewy if he could improve the design of their machines. He said he could do it in three days and would charge $500 if the design was not good; $2,000 if the design was used.

After celebrating with champagne, Loewy ordered a hundred pounds of modeling clay, tools, and a floodlight. Gestetner loved the design, put it into production in the early 1930s, and hired Loewy to do more work. Thus began his career as the most important industrial designer of all time.

Throughout that career, Raymond Loewy believed in beauty in commerce. Never a proponent of “art for art’s sake,” he said, “The goal of design is to sell. The loveliest curve I know is the sales curve.”

As his career evolved, Loewy carefully crafted and developed his image as a European sophisticate. His clothes, homes, and custom-built cars were always striking. He said that “a good life has been as important to me as my work; in fact, the two of them are bound up in each other.”

Despite his high income, the stock market crash of 1929–30 put him “$125,000 in the hole,” but he soldiered on, always believing in himself.

In 1931, Raymond Loewy married Jean Thompson. While they divorced fourteen years later, Jean remained a friend and key executive at his growing companies.

Raymond always loved cars. He had filed patents on a headlight, a radiator, and two automobile bodies when in the early 1930s he was hired by Hupp to design new Hupmobiles, resulting in the 1932 Spyder and 1934 Sedan, both advanced designs for the era.

During that same era, other designers began to share Loewy’s visions of better design. Respected competitor Henry Dreyfuss and Walter Dorwin Teague stand out. Visionary designer and author Norman Bel Geddes later drew acclaim for his work on the 1939–40 New York World’s Fair. Competitor Henry Dreyfuss had redesigned appliances for Sears, Roebuck, but in 1933 accepted a refrigerator assignment from Sears’s competitor General Electric. Unwilling to work for two competitors, he recommended that Sears contact Loewy for their refrigerator redesign. Sears asked Loewy to do a new design for its 1934 Coldspot refrigerator. Again starting with clay modeling, Loewy designed a streamlined model that was easy to clean. He charged Sears $7,500 plus a $25,000 bonus if sales hit high levels (taken together, $600,000 in today’s money). Sears also gave the new model six cubic feet of space when the norm was four cubic feet, but the retailer kept the price competitive (Sears always believed in saving the customer money through better features). For the next few years, Loewy continued to work with Sears, adding such features as aluminum shelf racks and crisper drawers. While he believed in timeless design, he also supported continuous improvement. In 1934, Sears sold 30,000 Coldspots and ranked eleventh among refrigerator providers. By 1939, Sears was selling 290,000 per year and ranked second in the industry.

The Sears Coldspot put Loewy on the map, gave him increased visibility, and enabled him to hire his first employee. He had also opened an office on Fifth Avenue. He soon added designers, a business manager, a public relations person, engineers, a model shop, and a clay and plastic modeling department. For an office party, he hired an unknown singer from Hoboken, New Jersey, named Frank Sinatra.

Raymond Loewy, Henry Dreyfuss, and Walter Dorwin Teague can be viewed as the creators of a new industry, the industrial design business. They were as much entrepreneurs as artists.

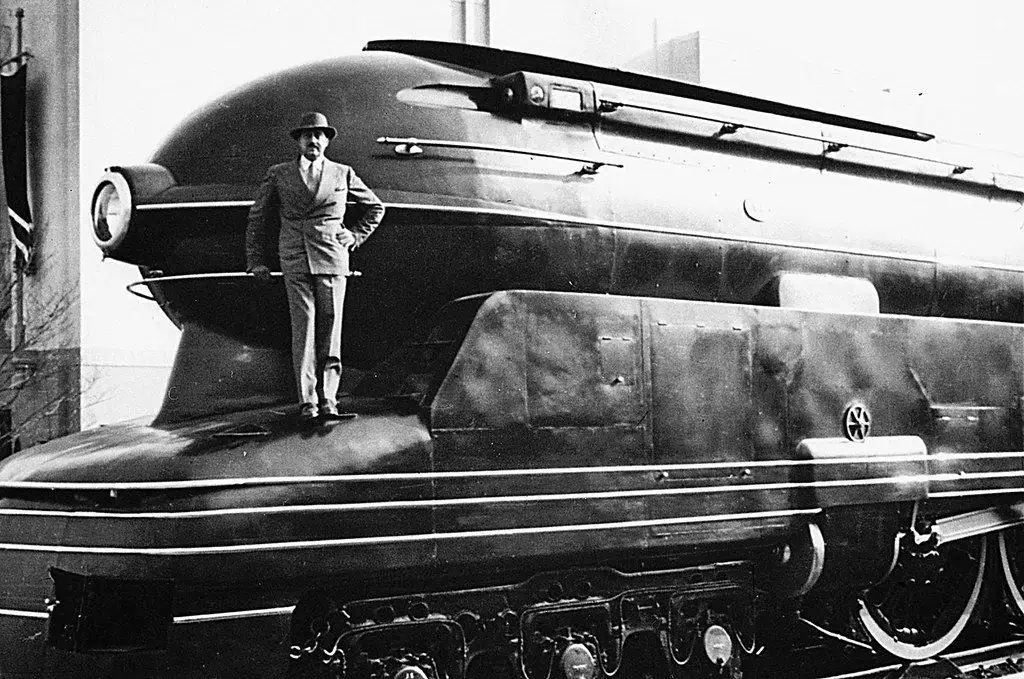

The Pennsylvania Railroad

Perhaps nothing inspired Raymond Loewy like the wonder of the age: the steam locomotive. He had watched and drawn them since his youth. Through one of his New York society contacts, he got an interview with Martin Clement, the president of the Philadelphia-based Pennsylvania Railroad, the most successful and best-run line in America. Loewy wanted to work for the railroad.

Clement asked, “What did you have in mind?” Loewy’s answer came quickly, “A locomotive.” Clement responded, “The trash cans in the New York Terminal (Penn Station) are terrible. What can you do with them?”

Most people would have walked out the door at that seeming insult. Not Raymond Loewy. He then spent three days studying the trash cans and how they were used. He charged the railroad $119 for three prototype designs.

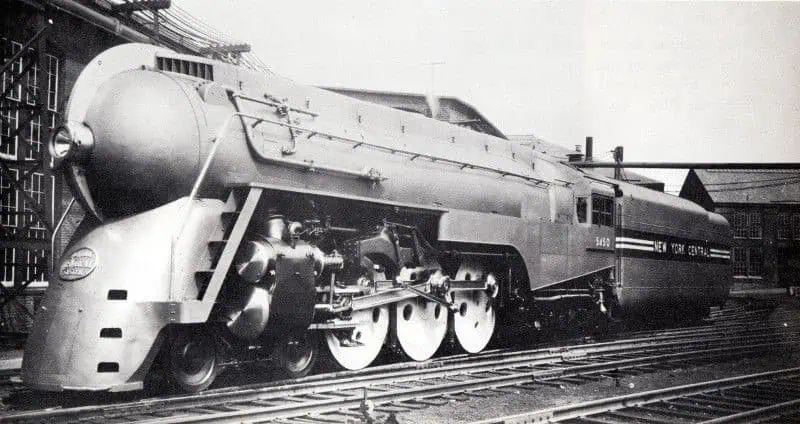

Such was the beginning of one of the most important corporate relationships in Loewy’s long career. He was soon asked to take a look at the railroad’s locomotives. He rode in the cabs, holding a stick out the window with a white ribbon attached to the end to measure the airflow. He added toilets for the engineers. In 1934, he designed the Pennsylvania’s GG1 electric locomotive, one of the most beautiful, powerful, and fastest electric locomotives ever built: it could haul a twenty-five-car passenger train at a hundred miles per hour day after day. The GG1 remained in use on the New York to Washington route until 1983.

Next, the Pennsylvania asked Loewy to redesign its workhorse locomotive, the K-4 Pacific type. His 1936 streamlining resulted in the engine using three hundred less horsepower to go ninety miles per hour.

As Raymond Loewy’s annual retainer from the railroad grew from $20,000 per year to over $100,000 by 1939 (almost $2 million today), he worked on everything imaginable for the company. He said, “In our country, there is always a chance of success for everyone who knows how to do a thing well, delivers it on time, and sticks to his word.” Loewy was unafraid to charge what the market would bear. Projects for the railroad included passenger car interiors, menu design, signal towers, a bridge over the Potomac, coffee cups, and even a bronze tablet for a retiring executive. Nothing bored Loewy or escaped his eye. He found the clocks in New York’s Pennsylvania Station hard to read and submitted an unrequested proposal to improve them.

The height of Loewy’s “power” with the railroad was expressed in the stunning 1939 S-1 locomotive, 140-feet long and weighing over a million pounds. It could pull a fourteen-car train at up to 140 miles per hour with its seven-foot diameter wheels. As a star of the New York World’s Fair, it was placed on a treadmill and ran at full speed in front of the thrilled visitors. As he had been since a child, Loewy was always equally thrilled, often traveling to remote locations just to see one of his huge locomotives speed by.

Loewy’s 1942 T-1 freight locomotive was another compelling design for the railroad.

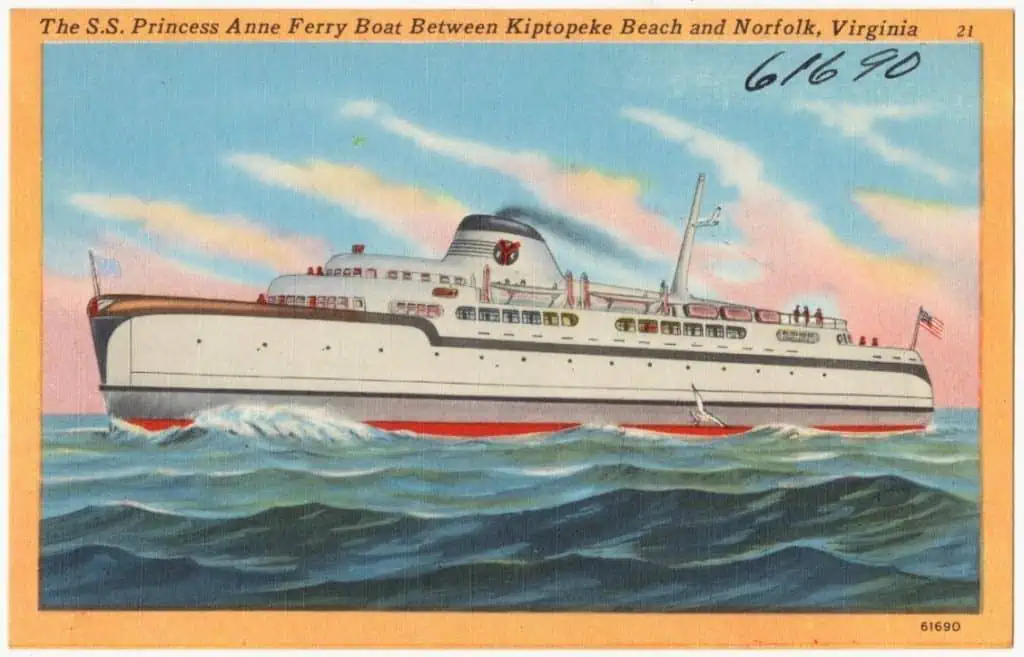

Perhaps Loewy’s most beautiful work for the Pennsylvania Railroad was his 1936 design for one of its 342 boats, the ferryboat Princess Anne. Some 260 feet long, the ferry was the largest and fastest of its type, and included a dance floor, snack bar, and restaurant.

His work for the top railroad led to interior designs for such famous trains as the Burlington Zephyr, the Santa Fe Super Chief, and the Pennsylvania’s own New York to Chicago Broadway Limited. Loewy worked with other top designers and at the same time was a competitor. Their efforts resulted in better and better products, as they observed each other’s work. For example, Henry Dreyfuss streamlined the “Hudson” locomotives which pulled the competing New York Central’s crack Twentieth Century Limited, resulting in another classic of the streamlined train era.

Building a Business, Creating a Profession

After these many successes and related publicity, Raymond Loewy’s star rose, and he brought many others into his company, Raymond Loewy and Associates. He hired two designers from General Motors’ famous styling studios.

In 1936, William Snaith, a stage designer, joined him to plan and design retail interiors, which became a major business for the Loewy firm. The firm was among the first consultants to explore the psychology of consumers, tracking their movement through a retail space, noting their reactions to décor and lighting, and applying their findings. They advised supermarket chains and apparel stores, with clients ranging from Lord & Taylor and Macy’s on the East Coast, to Hudson’s in Detroit, to Lucky Stores on the West Coast. The department stores of the 1950s and 1960s reflected their vision. Their unprecedented interior for the “windowless” new downtown Foley’s in Houston in 1947, built for Federated Department Stores, made Time and Newsweek magazines. The store, one of the few new downtown stores in America at the time, enabled stockrooms to be placed around the perimeter of each department, instead of in the basement or otherwise far removed.

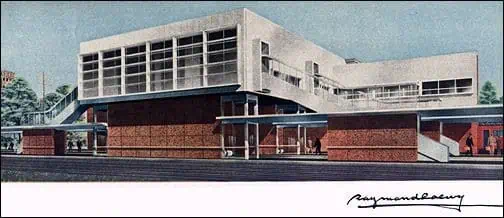

The firm even designed a train station for the Norfolk and Western Railroad in its headquarters city of Roanoke, Virginia, today the location of two museums and a gallery about Loewy.

Raymond Loewy paid his people well and created a profit-sharing system. But he knew that his “persona” was critical to the selling effort, and every final product went out over the Loewy name, not the name of the individual designers. Even his signature, like that of Walt Disney, was designed. Yet many learned well, and some went on to create their own firms, or head design schools. Young Gordon Bunshaft was among them—he went on to be a senior partner at top architecture firm Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, and designed the pacesetting modernist Lever House in New York, among other famous buildings.

Loewy’s key requirement was that any new hire must be able to draw just about anything and draw it fast. By 1938, he had hired eighteen designers, rising to fifty-six three years later.

Jay Doblin, who later headed the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology, described life at the firm, where he had begun as an office boy: “During the late forties and early fifties, the Loewy office represented a truly marvelous design era that will never come again. There was fun and gaiety, prank-playing and camaraderie amongst us, and the work itself was incredible. . . . At [age] thirty, I was designing for Nabisco, Shell Oil. I had a free pass to go anywhere in the world, hire anybody and build as many models as I wanted. There was always plenty of money. Loewy was running a $4 million operation with upwards of two hundred employees, so the place was packed with amusing and talented people.”

Loewy also hired women and ensured their fair treatment. Designer Audrey Hodges later said, “Each of us was given a number for our designs. They didn’t go by name; we were given a number, so no one ever knew whose work they were judging.”

A key addition in 1940 was Betty Reese, his publicity and public relations expert. Reese instructed him to stand to the right of big shots when pictures were taken, as Loewy would then appear in the photo on the left, and his name would come first in the caption.

The man knew how to change the minds of others, how to sell them on his vision. Reese said, “Loewy prepared for his presentations like a boxer preparing for a big match. He wouldn’t eat; he’d be at the office hours before everybody else; he’d practice every word, every joke.” She went on to say, “Loewy made sure to orchestrate the clients’ first view of his designs. If it was a car, for example, he would show it to them first from an impressive distance, from the end of a very long studio. He had learned that if the clients were allowed to get close to the car in a casual way, they would start picking it apart. He wouldn’t let them get near it until they had experienced it as a complete finished design.”

Loewy sketched initial ideas and edited every design. He had “an extrasensory talent for knowing the consumer marketplace” and “an uncanny feeling for what a product should look like.” While always pushing for better design, Raymond Loewy also realized there were limits to what the public would accept, resulting in his key concept of MAYA: “Most Advanced Yet Acceptable.” He also believed in streamlining and simplicity, viewing the egg as the most perfect package ever created.

When he hired Reese, he told her he wanted to be on the cover of Time magazine, which took her aback. But over eight years later, in October of 1949, they finally achieved that goal.

Despite his early start as an illustrator, Loewy developed the reputation of being a poor draftsman. Perhaps that resulted from his surrounding himself with people who could draw better than he could. In contrast, his competitor Henry Dreyfuss was an excellent draftsman, even able to draw every idea upside down when sitting across the desk from a client.

While he took all the credit, could be aloof, and often spent his summers in luxurious homes in France and winters in Palm Springs, California, his ideas and personality were ever-present. Reese said, “The office would sometimes put on shows in which they’d spoof Loewy’s inability to draw or even his superficiality, but he was always the one to laugh loudest.” He was known for the compliments he would pile on the best artists and draftsmen.

As time passed, the Loewy design firm added more and more clients. He opened a highly profitable Chicago office, and in 1934 his first London office, which designed the Sunbeam Alpine car, Raleigh bicycles, the AGA stove, and restaurant interiors for the big Lyons Tea House chain.

Raymond Loewy urged his clients to develop a “long-range design philosophy.” Later IBM adopted such a philosophy led by industrial designer Eliot Noyes, and today we see the same at work at companies including Apple and Target.

Loewy required that his shop staff be “full service,” willing to design anything that came their way. They increasingly worked on “corporate identity” and logos (including airlines TWA and United), packaging, and every other thing imaginable. They designed eggbeaters and stainless-steel kitchenware for industry leader Ekco Products (earning a retainer of up to $75,000 per year), meat cans for Armour, china for Rosenthal, fountain dispensers for Coca-Cola, and ham radios for Hallicrafters. Over the years, more than five hundred members of his staff worked on the big Nabisco account, made difficult by squabbles with the company’s management. While competitor Henry Dreyfuss worked for John Deere, Loewy designed tractors, trucks, 1,800 dealership buildings, and an outstanding logo (in the image of a farmer on a tractor) for Deere’s then-larger competitor, International Harvester.

International Harvester Tractor

International Harvester Logo

International Harvester Dealership

Raymond Loewy, along with Henry Dreyfuss, Walter Dorwin Teague, and ten others created the Society of Industrial Designers in 1944, the first professional organization for the field. The SID established ethical standards and only accepted full-time designers who worked on a broad scope of projects.

The Frigidaire Story

After working with Sears on refrigerators, he and the company parted ways, and he accepted work for General Motors’ Frigidaire Division in Dayton, Ohio—one of the top makers of refrigerators. Always a great storyteller, Loewy reveled in the following one, which took place after dinner and wine with Frigidaire’s General Manager Elmer Biechler. Late at night, Biechler drove Loewy out to watch the shift change at the Frigidaire plant.

Loewy wrote, “No sounding of horns, no brake screeches, only a mighty purr, a feeling—of order, precision, power. As we reached the crest of a hill we could see the stream of red taillights and the stream of white headlights fading away in the distance. The sprawling plant was ablaze with blue mercury light. Over certain areas the sky was shivering with the blue-white flashes of automatic welding. White, green, red and blue signal lights would punctuate the night. The whole sky was aglow. . . . I was utterly moved by the magnificence of it all. It was like seeing the actual flow of the rich, red blood of young, vibrant America. . . . We paused in a quiet spot, and Biechler took my arm and said: ‘Loewy, boys work on our problem, in your penthouse office on Fifth Avenue, you may not realize the real importance of the pretty lines you put on paper. You see, every one of these men around us supports a family of four. . . . They all live well because they have a job. They have a job because, among other things, your design clicked. In this plant alone—and we have dozens of others all over the world—eighteen thousand men are employed. Eighty thousand dependents! And remember for each man employed at the plant, there are three in the field: salesmen, advertising men, maintenance men, traffic and transportation fellows, warehousers and accountants, dispatchers and repair crews, electricians, statisticians, engineers, draftsmen, etc. That’s another sixty thousand. If you add to that another 250,000 for dependents, you get a true picture. More than 320,000 people whose life is directly affected by the success of what you put on paper!’”

This story was key for Loewy, and he shared it when training his new staff members. He said, “We never lose contact with reality, and we do not underestimate our social responsibilities. As we have over one hundred active clients on our list, it may well be that the soundness of our designs affects the lives of millions.”

But above all else, he was concerned about the lives of the ultimate customers, saying, “I believe one should design for the advantages of the largest mass of people, first and always.”

More Transportation

Despite becoming the largest retail store design firm in the nation, and later renaming his company Raymond Loewy/William Snaith, Inc., in honor of his revenue-producing partner, the retail business never captured Loewy’s heart—that remained in motion, in transportation.

In 1939, the firm had designed the interior of the Boeing Stratoliner airliner, and in 1947, the interior of the powerful piston-engined Lockheed Constellation. Much later, they did the same for the Air France Concorde supersonic transport. They also did interiors for ocean liners.

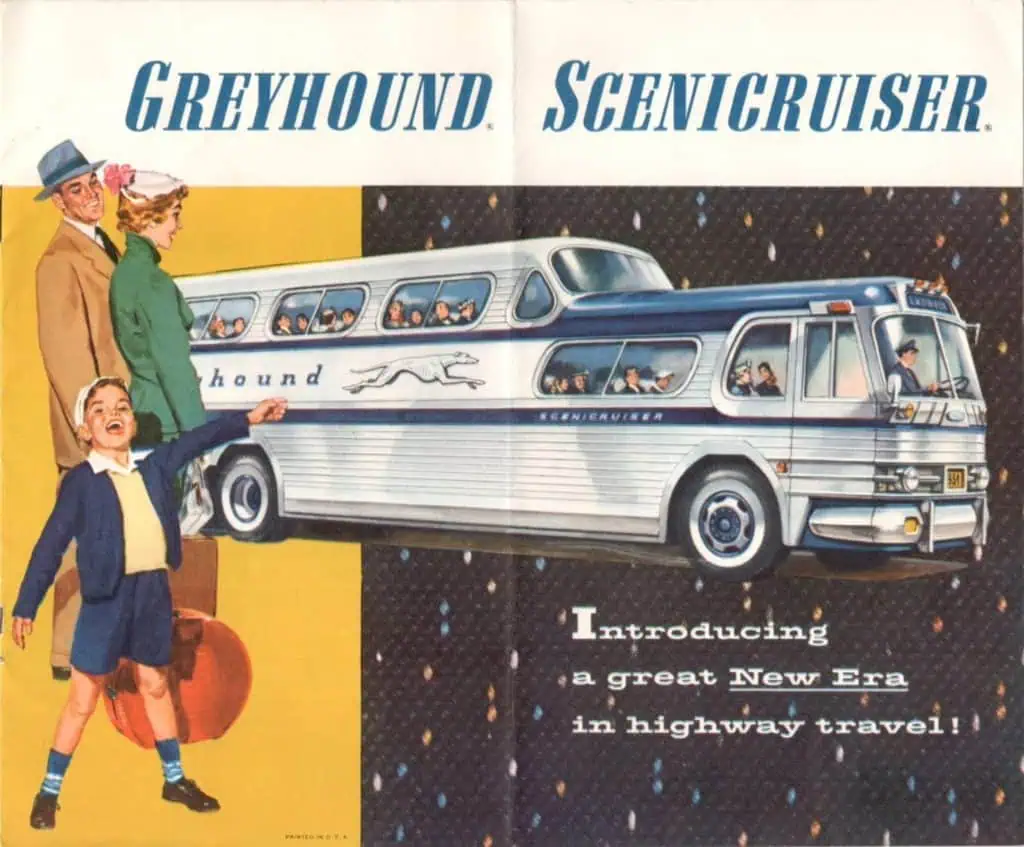

The Greyhound Bus company, for decades the largest carrier of passengers in the world (larger than any airline or railroad), came to the Loewy office in 1939, asking for new paint schemes on their buses. Raymond Loewy told the head of Greyhound that their dog logo looked like a “fat mongrel.” Loewy contacted the American Kennel Club to learn more about the actual shape of greyhounds, resulting in a sleek new dog that is still used today.

Delayed by the war, Greyhound began to introduce new Loewy-designed buses in 1946, but the real advance came in 1954, when the bus company introduced his double-deck “Scenicruiser.” The air-conditioned bus with a restroom and air-cushion suspension changed the intercity bus industry. Loewy was so proud of the bus that he rented a showroom on New York’s Park Avenue to show off a full-scale mockup.

The Studebaker Story

No client brought more acclaim to Raymond Loewy and his staff than automaker Studebaker of South Bend, Indiana. Founded in 1852, the company by 1887 was the “biggest vehicle house in the world,” the leading maker of wagons and carriages. In 1897, John Studebaker’s son-in-law, Frederick Fish, convinced the company to enter the automobile business. At first it produced car bodies for others; then introduced its first cars in 1902, followed by the acquisition of other car makers. In 1936, Studebaker remained one of the biggest “independents” (not one of the Big Three: GM, Ford, and Chrysler) alongside Hudson, Nash, and Packard. Chief executive Harold Vance invited Raymond Loewy to do some work on the 1938 line, then in the planning stages.

Over time, Loewy convinced Studebaker management that the company should differentiate itself by offering lighter, more fuel-efficient cars, an unusual thought for the era. He believed that there was an unmet market for “a slender, compact automobile.” Loewy’s firm added an office and studio in South Bend, which was plastered with signs that read: “Weight is the enemy.” Studebakers soon weighed 15 percent less than comparable Fords and Chevrolets, getting 25 percent better gas mileage.

The king of auto designers and father of big fins, Harley Earl at General Motors, mocked Loewy as a “refrigerator designer.” Yet Loewy had an important impact on future car design. Loewy kept adding staff on the Studebaker account, including young Virgil Exner from General Motors, who went on to head Chrysler’s successful 1950s design department. Another famous car designer—earlier responsible for the incredible Auburn, Cord, and Duesenberg cars—Gordon Buehrig joined the team. Loewy also paid close attention to the interiors of cars, having women designers focus on that work. Loewy’s 1938 Studebaker Champion was a hit, followed by the 1939 President which was named “the best-looking car of the year” by the American Federation of the Arts. Studebaker hired 1,500 new workers to meet the demand. In 1950, Studebaker hit its high point, selling about three hundred thousand cars, including the renowned bullet-nosed model, inspired by the fighter jets of the era.

Loewy and his team engaged in continuous turf and ego battles with Studebaker engineers and executives, but his persuasive powers usually won out. The sporty 1953 Starliner was widely acclaimed and proved there was a market for a “personal luxury car,” opening the way for the Ford Thunderbird, Buick Riviera, and Chevrolet Corvette. Unfortunately, Studebaker thought people would prefer the four-door sedan, but they wanted the sleek two-door coupe, which the company could not produce fast enough.

By the mid-fifties, Loewy was charging Studebaker a million dollars a year ($9 million today). But the struggles with management and declining fortunes of Studebaker led him to close his South Bend office in 1956. Nevertheless, this was not to be Loewy’s last (or most remembered) effort for Studebaker.

In 1961, new Studebaker chief Sherwood Egbert brought Loewy back to South Bend to create the Avanti, introduced in 1962. The fast, all-fiberglass car set twenty-nine speed records for a stock production car on Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats. The first American car to have disc brakes, with a dashboard lit red at night for easier visibility, the Avanti took American car critics and buffs by storm. While the Studebaker firm finally gave up making cars in 1963, Avanti fans continued production of the phenomenal car for several more years. The Avanti continues to be considered a highly collectible classic automobile, and one of Loewy’s most famous designs.

These beautiful Studebakers were not Loewy’s last transportation efforts. In the early 1960s, he designed the interiors and exterior paint scheme of Air Force One for his friends John and Jackie Kennedy. The latest versions of the president’s plane continue to use Loewy’s elegant paint scheme.

At the extremes of the transportation field, Loewy was asked to design NASA’s Skylab and spacesuits in 1967. His most important contribution was that he added a porthole to Skylab so that the astronauts could (literally) see the world. The work gave the seventy-five-year-old great pleasure and publicity, which he made the most of.

Living Life to the Fullest

After divorcing (but remaining friends with) his first wife, Jean, three years later (in 1948) Loewy married Viola Erickson. That marriage lasted the rest of his long life. Always well-dressed, always at his side, helping at the company, Viola was his constant companion.

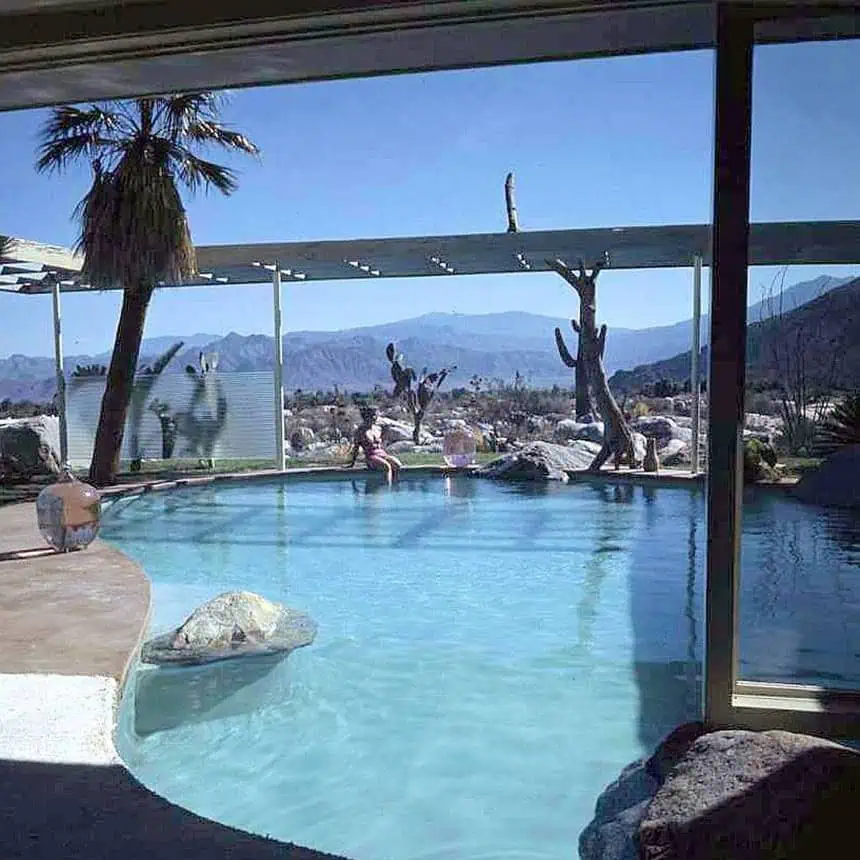

Loewy’s cars were custom-built to his own designs, as were his fabulous houses (two in France, one in Palm Springs, California, and one outside of Mexico City, as well as his New York apartment). His Palm Springs house had an indoor–outdoor swimming pool that edged right up to the front door, causing some famous guests to fall in fully clothed. He hung out with comedian Jack Benny and actor William Powell. His French country estate was built in the sixteenth century by King Henry IV for one of his mistresses.

Of his lifestyle, he said, “Thus we live a life which, to us, is ideal. It is a blend of everything that makes life interesting and eventful. America gives me the opportunity to be creative and imaginative. Europe—and France in particular—brings relaxation and perspective. This slowing down is imperative in order to maintain a balanced outlook. It also gives me a chance to appreciate America more keenly.” Loewy grasped the American energy, creativity, and opportunity like few others have.

The man never lost his zest for life. At seventy, he took high speed driving lessons with auto legend Carroll Shelby. At seventy-seven, he and Viola were careening around California beaches in a high-powered dune buggy. He loved racing, deep-sea diving, and speedboats.

By 1973, the eighty-year-old Loewy had 190 employees in New York, 48 in Paris, and 20 in London. But he finally decided to retire, selling his businesses in 1976. He still had energy left, beginning his book Industrial Design in that same year.

Raymond Loewy died on July 14, 1986, at the age of ninety-two. To call his life well-lived would be the ultimate understatement. To see his impact on our world, all you must do is open your eyes.

Sources and Further Reading: This biographical article is based on the book Streamliner: Raymond Loewy and Image-Making in the Age of American Industrial Design, by John Wall (2018). The best look into Loewy’s mind, and the source of most of the quotes in this article, is Loewy’s own 1951 autobiography Never Leave Well Enough Alone. Twenty-eight years later, Loewy published his design ideals in the excellent book Industrial Design (1979). Both of Loewy’s books contain many great illustrations of his diverse work, as do books on Loewy by Paul Jodard (1992), Phillipe Tretiack (1999 and 2005), and Glenn Porter (2002). Raymond Loewy: Pioneer of American Industrial Design (1990), edited by Angela Schonberger, contains fascinating articles about Loewy by twenty-one different writers. The best places to see Loewy on exhibit or learn about him are the Hagley Museum in Delaware and the train station in Roanoke mentioned above. To really meet the man, watch the 60 Minutes interview with Morley Safer; to see his work in a video, watch this one. For a broad look at Loewy, his competitors, and the best of Industrial Design through history, get the book Industrial Design A–Z by Charlotte and Peter Fiell (2019) and Founders of American Industrial Design by Caroll Gantz (2014).

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.