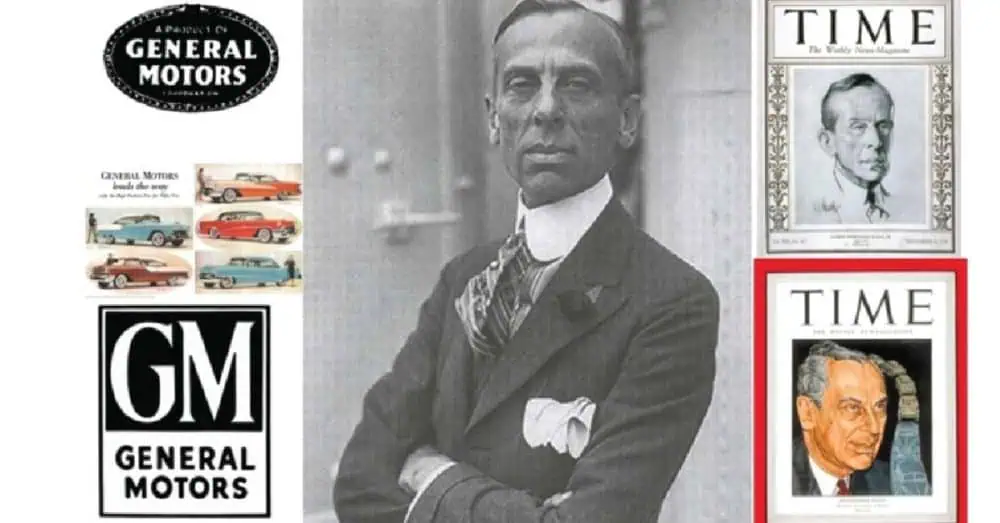

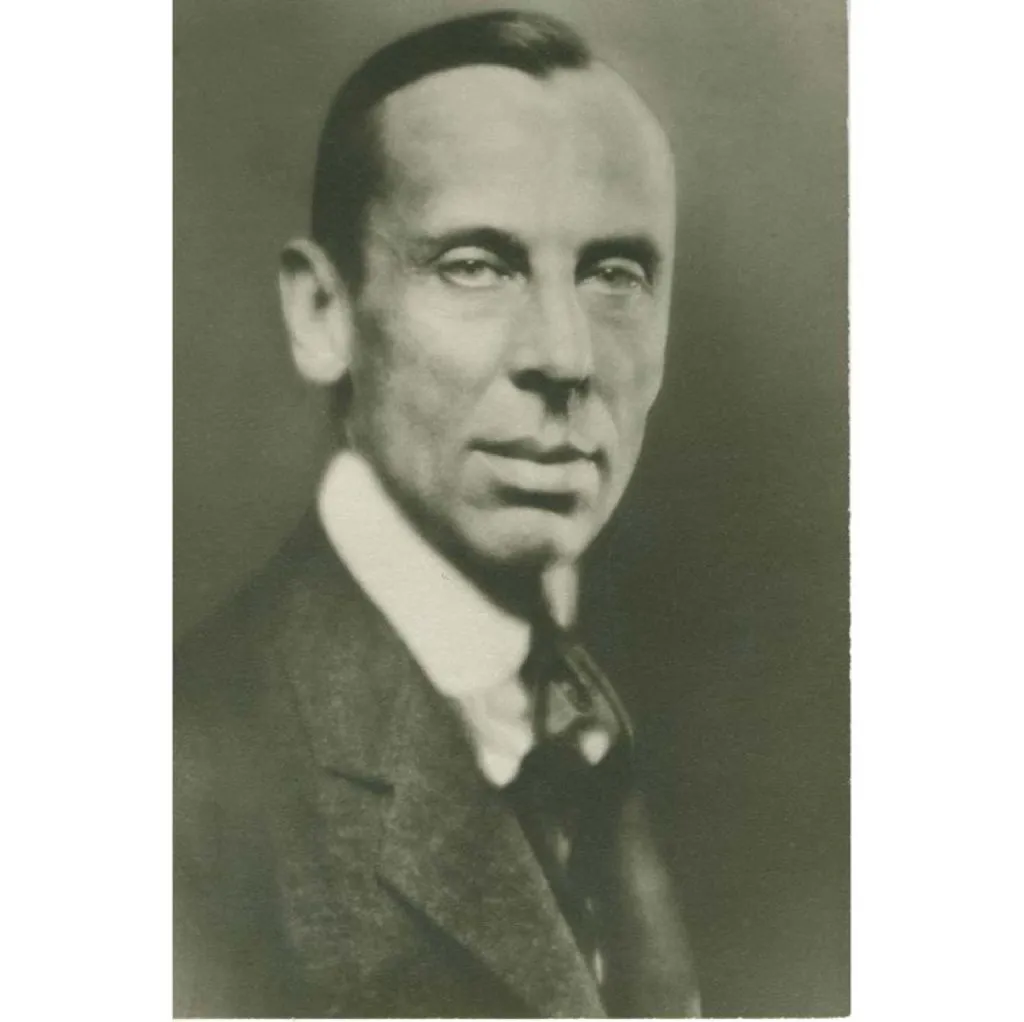

Many management scholars consider Alfred P. Sloan, Jr. as the greatest business leader in American history. If we exclude company founders, Sloan has few peers among those who led companies they did not found. After running a smaller company for twenty years, he sold the company to General Motors (GM). Sloan became President of GM in 1923 and continued in active leadership until 1956.

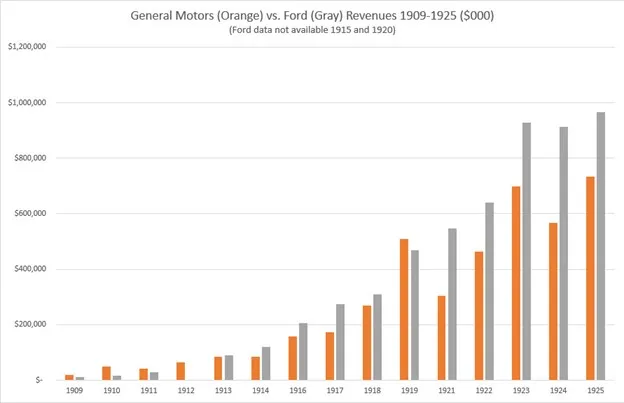

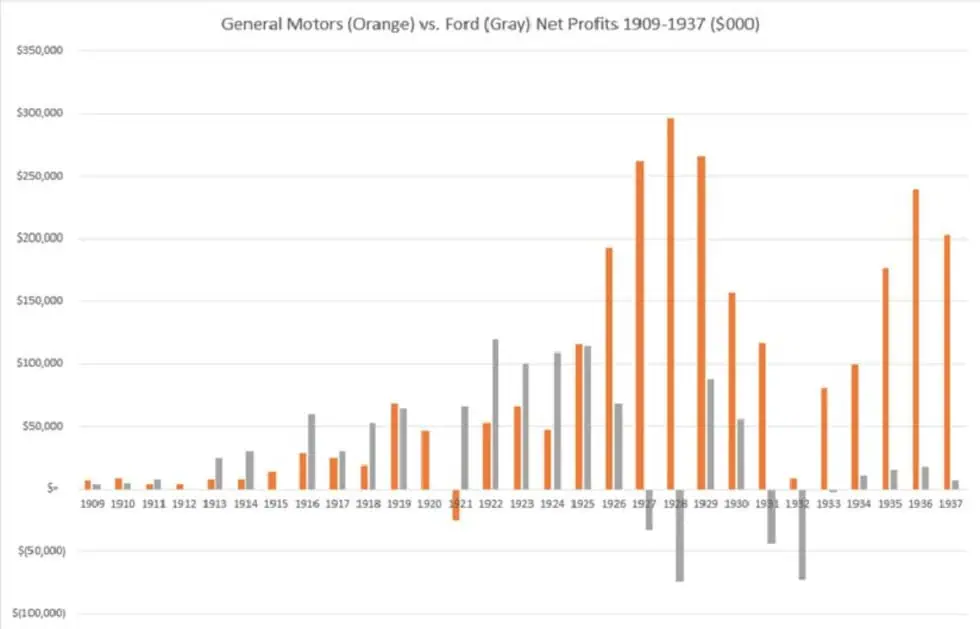

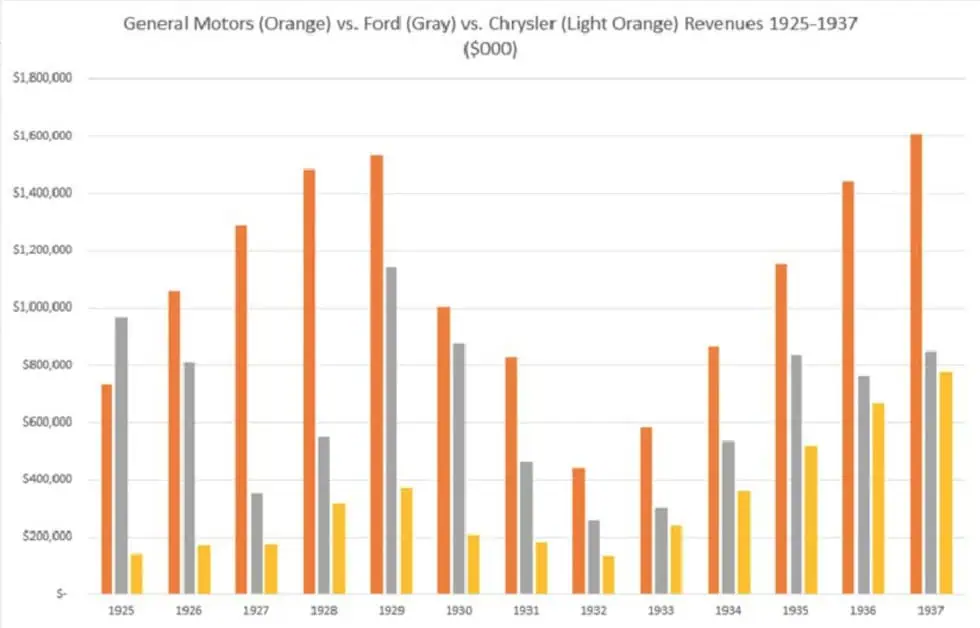

In 1922, the year before Sloan took charge, General Motors made a net profit of $53 million on sales of $464 million. Those profits were less than half the $120 million earned by arch-rival Ford. In Sloan’s last full year serving as Chairman of General Motors, 1955, company profits were $1.19 billion on sales of $12.4 billion. That 1955 sales figure, having grown at over 10 percent per year for thirty-three years, was double the next largest company on earth. Profits in 1955 were 50% higher than those at each of the next largest companies, Standard Oil of New Jersey (now ExxonMobil), Royal Dutch Shell, and American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T).

These results led business leaders around the world to study and attempt to mimic Sloan and his methods. Corporation after corporation adopted his theories and policies. Sloan is today far less known than such business luminaries as Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, or the late Steve Jobs, though all have applied some of his ideas, whether they knew it or not.

Thousands of pages of books and articles have been written about Alfred Sloan and his management style and decisions. Renowned management thinker Peter Drucker’s third book, The Concept of the Corporation (1946), was an in-depth look at the company and propelled Drucker to fame. The first book written by the greatest business historian, Alfred Chandler, Strategy and Structure (1962), was in part the story of GM. At the age of eighty-eight, Sloan published his own magnum opus, My Years with General Motors (1963), reportedly the bestselling business book in history at the time. Bill Gates has said that if you are only going to read only one book about business, it should be Sloan’s book, which served as an inspiration to Gates in building Microsoft.

Sloan can be a challenging man to understand and portray. Many pages have been written on the history of General Motors and Sloan’s role in that history, but writers have been frustrated by the lack of personal details about Sloan and his life. The man wanted it that way.

Here we take a somewhat different approach to Sloan’s life, taking the measure of the man. Unlike most of those who have written about him, your writer has the added perspective of having built and run companies worked for top management at huge enterprises, and served on boards of directors of public companies. Here, from our vantage point, is the story of Alfred Sloan, his life, his work, and his legacy.

Beginnings

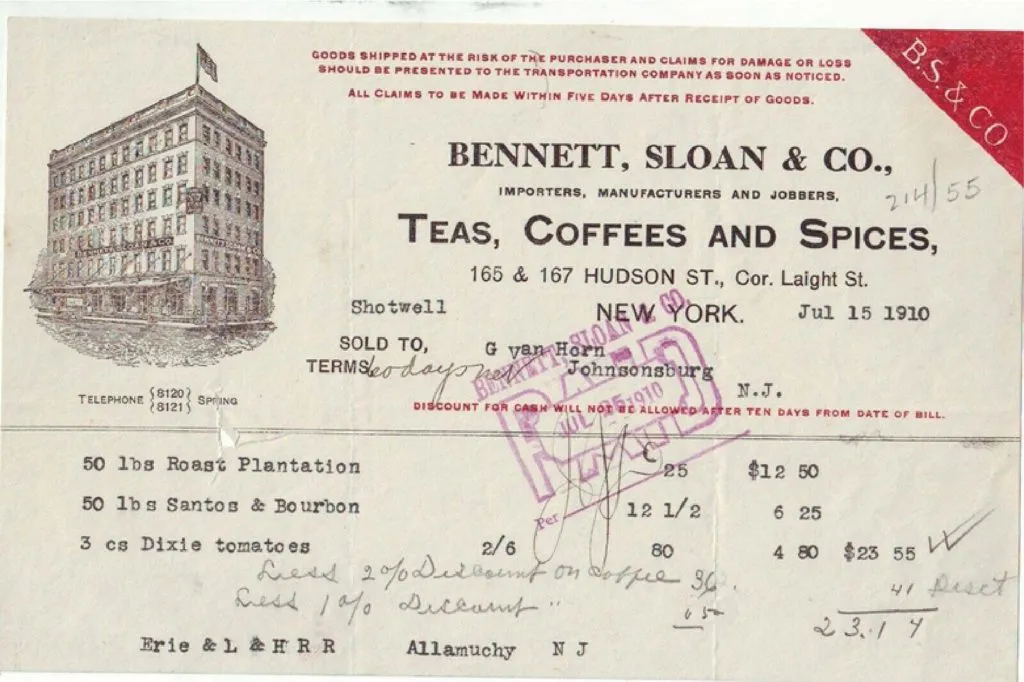

Alfred Pritchard Sloan, Jr. was born in New Haven, Connecticut on May 23, 1875 to coffee and tea merchant Alfred Sloan and his wife Katherine, the first of five children. Ten years later the family moved to Brooklyn to be near the father’s Manhattan-based business, Bennett, Sloan, & Company. The young man developed a Brooklyn accent that stayed with him for life.

Sloan, the son, grew up in the era of Edison. New inventions were everywhere. The telephone and electricity were coming into widespread use at the same time the automobile was being invented. Like many young men of the era, these developments attracted the bright boy’s interest. He tried to get into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), but was too young. Finally admitted at the age of seventeen, Sloan completed the course in electrical engineering in three years, the youngest graduate at age twenty.

In 1895, the nation was still recovering from the intense depression of 1893. Jobs were hard to find. Sloan’s father arranged an interview for his son with the father’s friend, John Searles, head of the big American Sugar Refining Company in Brooklyn. Searles found a job for Sloan in a small company Searles had invested in, the Hyatt Roller Bearing Company in New Jersey. Alfred would start work as a mere draftsman.

Hyatt Roller Bearing

The Hyatt Roller Bearing Company made bearings that made machines function more smoothly, with less friction. The company’s products were tubular bearings which could carry a heavier load than traditional ball bearings. These unusual bearings had been invented and patented by company founder John Wesley Hyatt, who also pioneered the commercial development of celluloid, used to make billiard balls, piano keys, and false teeth. The roller bearings were used in bicycle gears and in the systems of pulleys and belts employed in factories, but the company was not particularly successful.

When Sloan arrived at the New Jersey plant, he found a shack-like structure next to a smelly dump. When it rained, the whole area became a sea of mud. The business lost money, its bookkeeper Pete Steenstrup returning week after week to Searles’ office, asking for more money to cover expenses. Sloan and the Norwegian Pete became close friends, continually discussing how they could improve the Hyatt Company’s prospects were they in charge.

Sloan was a serious, ambitious young man. He wanted to marry Irene Jackson, but his career outlook was too bleak for him to consider marriage. This lack of progress led him to leave Hyatt after two years, in 1897. Alfred joined a company developing a refrigeration system for hotels and apartment buildings. Refrigeration was another technology just coming into its own. Working for inventor Michael Wood excited the twenty-two-year-old Sloan. The company’s idea was to have a central cooling system that circulated cold to individual ice boxes in each room or apartment. Sloan designed the circulation system. He also built up the courage to marry Irene, in September 1898. But soon after, the refrigeration company failed. Luckily for Sloan, Hyatt investor Searles had financial troubles and wanted to sell the money-losing Hyatt Roller Bearing Company. Equally fortunately, Sloan’s father and a friend had the $5,000 required to buy the struggling business and limited additional funds to invest until the company became profitable. They wanted Alfred to return to Hyatt and take over, which he did, at the age of twenty-three.

Sloan and Pete Steenstrup took over the business, Alfred did the engineering and Pete handled sales. Both realized that the emerging auto industry, then in its infancy, held great opportunities for Hyatt. Pete was soon visiting every major automaker. Pete tried to get Alfred to spend more time making sales calls with him because Pete could not talk the language of their engineer customers. At first, Sloan resisted but eventually started visiting Detroit and meeting industry leaders, including Henry Ford and Billy Durant, the colorful founder of General Motors.

A key event in Sloan’s life took place when he met with Henry Leland, the head of Cadillac. Cadillac was formerly the Ford Company, before the investors fired Henry Ford and he left to start the company which today bears his name. Leland was called “the master of precision” and had higher standards than any other automaker. He complained to Sloan that Hyatt’s bearings were insufficiently consistent, that Cadillac required interchangeable parts with tolerances within a few thousandths of an inch. Alfred got the point. He returned to New Jersey and improved Hyatt’s manufacturing processes and systems, rising to Leland’s challenge.

In the ensuing years, Alfred Sloan and Pete Steenstrup built Hyatt into a much larger, profitable company. While Pete retired, Alfred and his father became majority owners of the company and continued building it. Over half of the company’s revenue came from the Ford Motor Company, especially after the 1908 introduction of the Model T. Most of the remaining sales came from General Motors and its Buick, Oldsmobile, Oakland, and Cadillac divisions, which GM’s Billy Durant had acquired in a haphazard fashion.

Being at the mercy of two giant customers made Sloan nervous. He knew either company could make their own bearings, or switch to another supplier. Hyatt’s patents were set to run out, making the company’s position even more tenuous. Maybe Hyatt should sell out to a larger company if the opportunity arose.

Selling Out

Billy Durant was a born salesman and wheeler-dealer. He had bought a troubled Buick and turned it into the largest auto brand, before Henry Ford’s Model T took over the lead. Buying every auto maker that caught his attention, usually for stock, his General Motors had emerged as the second largest automaker, out of hundreds in the market.

At the time, the automobile companies were primarily assemblers, buying most components including axles, bodies, and engines from other companies. Based on his experience making horse-drawn carts before entering the auto business, Durant liked controlling key suppliers, assuring his company’s needs could be fulfilled.

This led Durant to create the United Motors Company in 1916 by buying up some of the best auto parts makers and combining them into one firm. Included in the combine were Remy Electric of Anderson, Indiana, New Departure Bearings of Bristol, Connecticut, Dayton Engineering Laboratories (DELCO) of Dayton (inventor of the electric starter), and Perlman Rim of New York.

Billy Durant wanted Hyatt Roller Bearing to be included in United Motors. Alfred Sloan convinced his skeptical board to ask for $15 million, a price they thought unrealistic. Durant, well-known for his generosity when buying companies, negotiated minimally and the final price was $13.5 million. As best we can tell, Alfred and his father evenly split $8-9 million of this (about $100 million each in 2021 dollars), making both men wealthy beyond their dreams.

However, the purchase was made with a combination of United Motors stock and cash. Sloan Senior and the other partners wanted mostly cash, so Alfred had to settle on taking more United Motors stock than the others. He was stuck with most of his personal wealth tied up in stock in a new company in an industry that many thought was highly risky.

With over 3,000 employees and sales of about $9 million, Hyatt was a gem in the United Motors portfolio.

Alfred Sloan thus felt it important to make sure United Motors succeeded. Fortunately, Durant made forty-one-year-old Sloan the President of United Motors and left him alone to manage and build the company. Sloan soon added Harrison Radiator and Klaxon Horns to the group. He also created United Motors Service, an organization that set up dealers across the nation to sell replacement parts made by the company. Above all else, Alfred started to test ideas and develop management policies to maximize United Motors’ success.

Two years later, in 1918 General Motors bought United Motors with GM stock. Alfred P. Sloan was now on the GM board of directors and head of all “accessory” (parts) divisions. He was forty-three years old and had twenty years of experience running businesses behind him. He was also a large shareholder in General Motors.

Initiation into General Motors

By 1918, Billy Durant has already been in and out of General Motors, losing control to eastern bankers, then creating the very successful Chevrolet, selling Chevy to GM, and regaining control. He was brilliant at putting deals together, even agreeing to buy out Henry Ford before Durant’s bankers refused to finance the purchase.

But Durant was not a good manager. Rather than studying the data and making logical conclusions, he relied on his intuition and flew by the seat of his pants. He assigned tasks to whoever was at hand, ignoring their backgrounds and fit. He made operating decisions without asking the opinions of the key operating people involved.

Interested in expanding overseas, the General Motors management team, including Alfred Sloan and Buick’s brilliant chief Walter Chrysler, sailed for Europe with their wives in July of 1920. Their charter was to evaluate the purchase of France’s Citroen. While Citroen did not meet their standards for a well-run business, the men had long conversations about how they would make GM more successful if they ran it. They all expressed concerns with Durant’s leadership style. General Motors needed to be better organized and managed. Alfred Sloan and Walter Chrysler became lifelong best friends, even after Walter tired of Durant and left GM to become a major competitor.

After the end of World War I, inflation took off. But then prices fell back down and the nation went into a deep recession in late 1920 and throughout 1921. Sears, Roebuck almost went bankrupt, but was saved by personal investments by owner Julius Rosenwald. General Motors posted a loss of almost $25 million, the first loss in company history. The company ended 1921 with $200 million worth of unsold cars. The stock crashed, and the ever-optimistic Durant bought shares to try to prop up the market, going deeper and deeper into margin debt to buy the shares. (Though Sloan’s personal wealth was tied up in GM stock, he never sold one share as the stock dropped from $85 per share to $7. The man had faith in the future.)

GM Stock Certificate Engraving

The DuPont family, owners of the giant chemical company, had first invested in General Motors in a few years before. With large profits made in their gunpowder business during the war, they had continued to buy into GM. To rescue their investment, the DuPont’s paid off Billy Durant’s debts. He left GM for the final time. Pierre S. DuPont reluctantly took over the Presidency of GM. (DuPont interests ultimately owned over half of General Motors stock,)

At the same time, Sloan wrote up his ideas on how best to organize General Motors. He sent his “Organization Study” to DuPont and did not at first get much reaction, but soon enough DuPont studied the report and liked it. Pierre DuPont made Sloan his assistant. DuPont also provided GM with talented managers, especially in the financial area, where the DuPont company excelled. John Raskob (who later built the Empire State Building with Pierre), Donaldson Brown, and Albert Bradley became General Motors officers. Also in the top management team were Charles Kettering, founder of DELCO and GM’s inventive genius, and the best auto production man in the industry, William Knudsen, who had started at Ford but left the tyrannical Henry and joined GM.

Sloan’s Policies at General Motors

Alfred P. Sloan, Jr. served General Motors, its stockholders, employees, suppliers, and customers as President of the company from 1923 to 1943, as Chairman of the Board from 1937 to 1956, and as Honorary Chairman until his death at the age of ninety in 1966. During that extended period, GM passed up the formerly dominant Ford Motor Company, became the largest company in the world, and served as a model for other big corporations. Key steps taken by Sloan included the following policies.

Re-structuring the organization

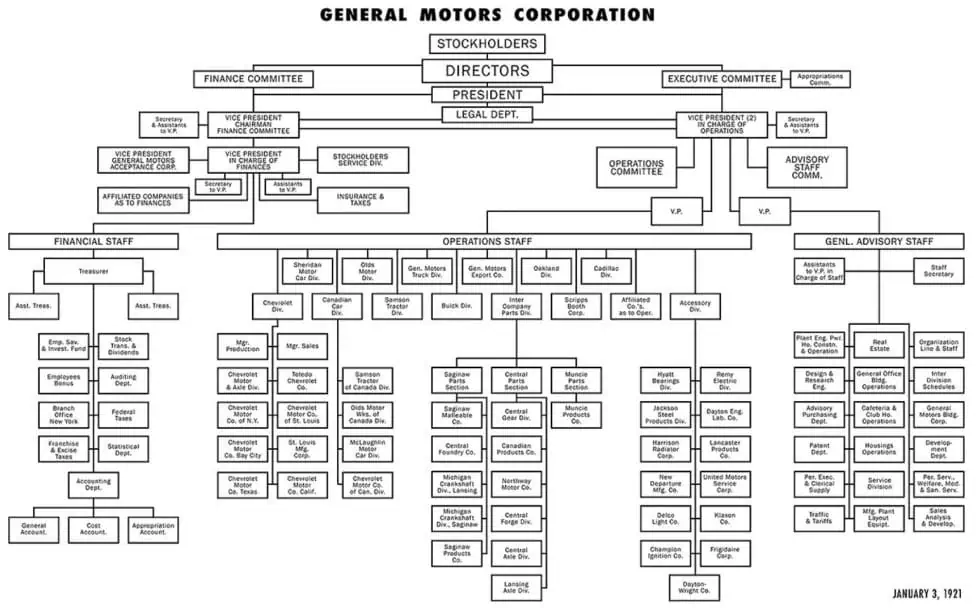

Sloan’s recommendations for how to structure the management of the company were put in place by Pierre DuPont even before Sloan was elevated to the Presidency, as shown in this 1921 organization chart:

This chart is the most important and most-studied organization chart in business history. (General Motors developed a long history of talking and writing about its policies and procedures for all to see, somewhat unusual in the business world.) Alfred Sloan achieved world fame as the man behind “decentralization.” The idea was that the manager of each operating division of the company, such as Chevrolet and Cadillac, had total operating freedom and control over their “profit center.” Place good leaders at the head of each division, and it would prosper. Don’t meddle in their business in the way that Billy Durant had.

At the same time, “headquarters” (including Sloan) needed to know how each division was doing in order to know if the company had the right people running the divisions. So this “decentralized system” was accompanied by a system of very centralized financial controls to monitor every aspect of the business.

While other companies around the world emulated this system, it was often oversimplified. Its complexity was not always understood, and the copiers had mixed results in applying the ideas. In reality, many functions besides financial controls were centralized. Sloan and his colleagues appointed the eccentric Harley Earl as chief of all design, affecting every operating division and every car and truck the company made. Charles “Boss” Kettering, the company’s technology chief, created and ran extensive research and development operations, some of the best in the world. His efforts led to innovation after innovation, leading the auto industry in new features. Fast-drying paint developed by Kettering and the DuPont Company permitted the mass production of colorful automobiles. Kettering also developed the first successful diesel-electric railroad locomotive and thus GM dominated that industry.

Many other important functions were likewise centralized, including legal, patent management, market research, purchasing of supplies, real estate, and factory design. Sloan’s system was a complex structure based on the logic of what worked best and which executives had the requisite talents.

At the head of the organization was a complicated system of committees, with the finance committee, executive committee, and operating committee at the top. Few if any key decisions were made by individuals. Alfred Sloan brought together the best minds in the company to deal with each issue.

His system focused on separating key policy decisions, such as where to invest more capital, how to differentiate the five car brands, and how to finance the company, from operating decisions. In other words, the committees determined what to do (and why) while the operators carried out the plans, the “how to do it.”

Throughout the company, the authority to make decisions was closely aligned with responsibility and accountability for results.

Those managers who produced results were well compensated. In the mid-1940s, GM President Charles Wilson was paid a salary of $352,000; fifteen other executives were paid $100,000 per year or more ($1.5 million in 2021 dollars). DuPont, paralleling GM policies as was often the case, had twelve executives earning over $100,000. By comparison, the head of #2 industrial company Standard Oil of New Jersey (now ExxonMobil) was paid $123,000 and no other executive there received over $100,000. At General Electric, the chief (also named Charles Wilson) made $125,000 and two others made over $100,000. General Motors executives were also awarded with stock, Sloan himself becoming one of the richest Americans thanks to taking GM stock starting with the 1918 sale of United Motors to GM.

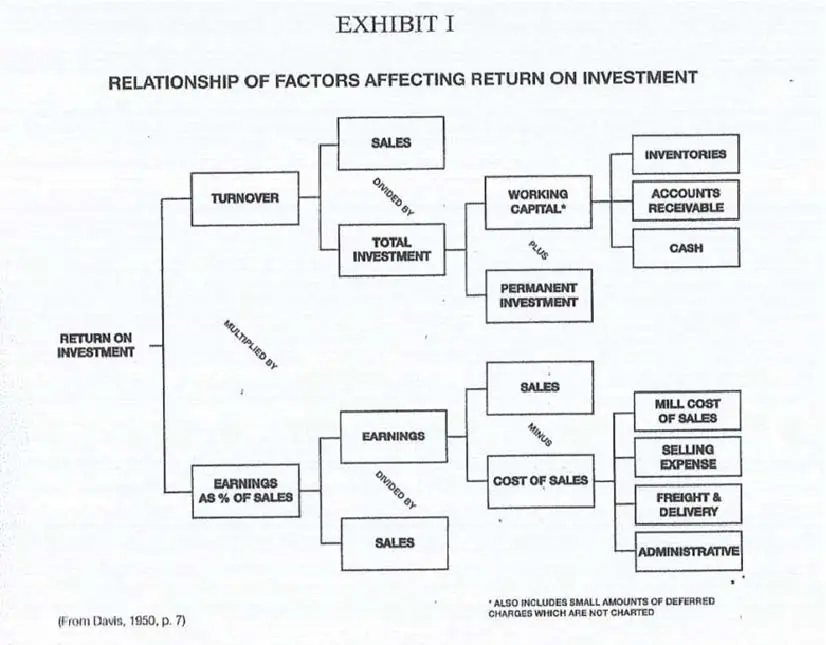

Financial Controls and Information Systems

Under Billy Durant, headquarters had little idea of how each division operated and whether it was truly profitable or not. The over-production of cars in the 1920-21 recession proved that. Sloan and his team, led by Donaldson Brown and the men from DuPont, developed the most sophisticated approach to how a company makes a profit yet developed. Key was the idea of “asset turnover,” the realization that tying up capital in excess inventory was unprofitable, and that return on investment was a more important figure than profits alone or dividends paid to shareholders.

The “DuPont Formula”

Sloan was obsessed with data, with the facts, and trained his colleagues on the use of them. The vast operating parts of the company religiously submitted various reports every ten and thirty days. But Sloan always wanted to learn more, to find more useful types of information.

For example, he realized that the company did not actually know how many cars were being sold by the dealers, sometimes resulting in making too many or too few cars. He hired a company to tally all new automobile registrations, by brand and by state, from government public records. Sloan had tens of thousands of surveys sent to auto buyers, asking them what they wanted in a car, and what they liked and didn’t like about GM’s products. Other automakers followed in his steps.

Most importantly, General Motors acted on the facts that they discovered.

Marketing

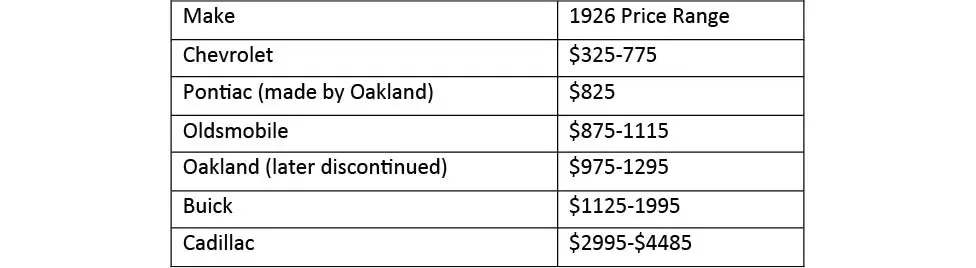

Not only did GM listen to what customers wanted. Sloan developed the idea of a car “for every purse and purpose.” When Sloan rose to power, many within GM thought it pointless to compete with Henry Ford’s low-priced Model T. Management considered dropping the Chevrolet line, priced just above the Model T, believing Chevy would never be very profitable. But Sloan believed in Chevy and kept it alive, under the manufacturing wizard William Knudsen and talented sales manager Richard Grant. Chevrolet had more features than the Model T for a slightly higher price. Chevy also moved more quickly to all-weather, closed-body cars than Ford, which still made many open cars.

By 1927, the Model T was dead and Chevrolet took the lead in the low-priced field. Having produced fifteen million Model T’s, Ford shut down his plant for months to retool and introduce the Model A. General Motors took the lead in terms of the total number of cars produced and sold each year and kept the lead in most years for decades.

In the Model T era, almost every new car buyer was a first-time car buyer. GM had to “invent” the idea of the used car trade-in, as well as pioneer time payments for cars with the General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC).

To carry out Sloan’s idea of a car for every purse, General Motors “laddered” its products, Chevrolet making starter cars, Pontiac offering a step up, Oldsmobile and Buick even higher, and Cadillac at the top, with slightly overlapping pricing.

Alfred Sloan also came to realize that the auto dealers often didn’t know if they were making a profit or not, or how much. General Motors developed accounting systems for its dealers that vastly improved their prosperity. (Henry Ford never put any emphasis on his dealers; they were forced to take however many cars Ford wanted to ship to them, no matter whether they had ordered more or ordered less.)

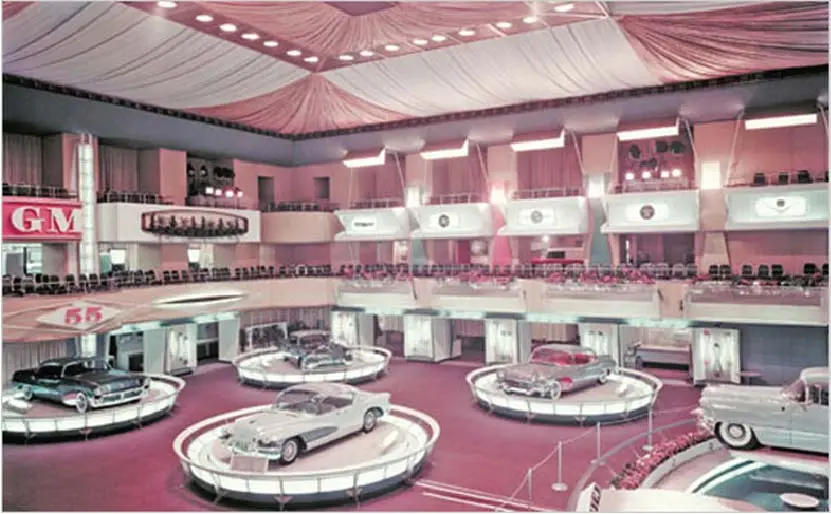

At General Motors, Harley Earl’s “Art & Color” department led the industry, by the 1950s making cars lower, longer, and finned. Other makers followed GM’s lead.

GM developed new ideas to keep the public interested, such as the “concept cars” in which Earl and his designers made “cars of the future” and took them on national tours. Futurama exhibits were the biggest hits at World’s Fairs in Chicago and New York.

General Motors pioneered the annual model change, sometimes (perhaps inaccurately) labelled “planned obsolescence.” GM’s laboratories and engineers were continually developing new features, such as automatic transmissions, power steering and brakes, and better engines. Sloan realized that these improvements would have the most impact if they were introduced all at one time, in newly designed models, once a year. GM’s annual Motorama tours of the new models were televised and toured the country.

Building a Global Transportation Equipment Company

Durant and DuPont had both favored international expansion. Alfred Sloan intensified this process, developing General Motors into an important car producer or importer in Canada, England, Australia, Japan, and many other countries. In 1929, GM bought Germany’s largest car maker, Adam Opel, which was far larger than Mercedes or BMW at the time.

In addition to Charles Kettering’s development of the diesel-locomotive, GM made trucks and was the leading maker of buses. Under Sloan, the company invested in the burgeoning aviation industry and made Allison aircraft engines.

The company produced a multitude of car parts, selling them to other automakers and to service stations as aftermarket, replacement parts. Batteries, radios, generators, and radiators poured out of GM factories.

Using its marketing and manufacturing talent, GM took Durant’s odd acquisition of a small refrigerator company and turned it into the best-selling Frigidaire line.

Putting the Policies Together The combination of a new organizational structure, financial controls, great marketing, and product line expansion led GM to become the largest industrial enterprise on earth under Alfred Sloan. Under his leadership, the company never lost money in the Great Depression. General Motors was also the largest supplier to the United States military during World War II, serving as the most important single company in America’s “Arsenal of Democracy.” The company blew past the competition:

Alfred Sloan the Man

In the many pages written about Sloan and his life, he is usually portrayed as being a man of steel, with ice water running through his veins. He cared nothing about people, had no life or interests outside of his work. He is depicted as formal and stiff, humorless, cold and heartless. Man as machine. Profit was all he cared about.

But we believe, if one sincerely tries to put themselves in Sloan’s shoes at head of a company upon whom hundreds of thousands of families depend, if one reads his own writings closely enough, another picture of the man emerges.

Most consider Sloan the ultimate organization man, “the man in the grey flannel suit” to use a mid-20th-century phrase. But Sloan spent eighteen years building Hyatt Roller Bearing from nothing into an important company. The man was at heart an entrepreneur, with entrepreneurial instincts.

Sloan is sometimes described as a remote executive, more interested in organizational structures than in technical details. Yet Sloan spent his youth and his early Hyatt years as an engineer, designing complex systems, improving manufacturing processes, and using his engineer’s love of math and logic.

Not unlike George Eastman of Kodak fame and Steve Jobs at Apple, Alfred Sloan rose from a technical background to become an astute marketer. Even in his early years at Hyatt, he complained to his automaker customers that they did not emphasize “eye appeal” enough. He thought design important, as did the later leaders of IBM and Apple. Sloan was not artless.

Perhaps Alfred Sloan, like many other industrial pioneers, was too complex for most observers to fully understand.

There is no question that in many ways Sloan was, as one might expect, a child of the 19th century. For most of his life, he was always formally and immaculately attired in spats and a stiff white collar. Everyone addressed him as “Mr. Sloan” and he likely addressed them in the same manner. This was not the era of casual dress Fridays and paternity leave.

Sloan left no love letters and had no children. Yet we do know that Sloan dedicated his first book, a 1941 autobiography, to his wife, Irene. When she preceded him in death after fifty-five years of marriage, he was distraught and did not hide it.

The man had a wry sense of humor. When he was pressed to admit before a Congressional investigation that GM was so ambitious that it wanted to sell a car to everyone in America, Sloan simply answered, “No, two.”

Sloan did not smoke, did not party hard, and seldom drank alcohol. But his best friend, Walter Chrysler, was a renowned “party animal,” to use a more current phrase. The two men and their wives vacationed together. Sloan enjoyed watching Chrysler make gargantuan bets in casinos, something Sloan was unlikely to do. The two reportedly did not talk business in their many conversations.

At work, Sloan was obsessed with objectivity, fairness, and honesty. He readily promoted people he did not personally like and fired people he liked. He worked hard to “keep personality out of decisions.” He did not socialize with fellow board members and executives. Pierre DuPont, the man who made Sloan President of GM and served alongside him on the board of directors, had one of the most fabulous estate gardens in America, Longwood Gardens outside of Philadelphia. Yet Sloan reportedly never visited DuPont’s home or gardens.

Most telling about Sloan is that he surrounded himself with diverse, even eccentric individuals.

Harley Earl wore suits that matched the color of the car he drove that day and kept a duplicate suit at the office in case he spilled something on his clothes. Donaldson Brown, the finance man, was known to be unintelligible to most people as he spoke in a combination of philosophy and algebra. Technologist Charles Kettering butted heads with Sloan over some of his inventions, but the two men were close enough to fund New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center together.

Anyone who has worked in a large corporation for any amount of time has witnessed some corporate politics and turf battles. Yet Alfred Sloan brought together a large team of diverse individuals who worked together smoothly for decades. Once a committee made an important decision, the full force of the company got behind and carried out that decision.

Sloan did not believe there was such a thing as being “a good judge of people.” He thought that the most important task of management was to put the right people in the right positions, adjusting for their strengths and weaknesses; that the only way to judge people was by their results. Alfred readily spent hours on picking “the right man” even for lower level management positions.

In his efforts to build a great business, Sloan continually travelled the nation in his private railroad car. Rather than asking dealers to come to his office, he visited them at their dealerships, asking probing questions, finding out how General Motors could help them prosper. He also visited GM factories around the world as he travelled.

The best clue to Alfred Sloan’s management style was that he was always the last one to talk in the thousands of meetings he attended. He asked probing questions, studied the data, and listened to every viewpoint. He did not give orders, he listened and sought consensus. He often supported decisions that he did not agree with.

While Sloan must have had enormous self-confidence, it appears his ego was never visible. His own personal needs never came ahead of those of General Motors, its stockholders, employees, and customers.

While the man had a temper, the strongest curse he uttered was, “That’s horse apples.” Evidence indicates that he controlled his temper, closing his office door when upset. Sometimes the person he was upset with not only kept their job, but got promoted if their results were good.

From everything we have read, Alfred Sloan must have been an exceptional boss. And for those other executives at GM who respected fairness, objectivity, and making data-based decisions, the work must have been a joy.

While Sloan was an intense competitor, he believed in a strong industry and enjoyed the competition. When key GM executive Walter Chrysler left the company, Sloan urged Chrysler to start his own company, which Chrysler did. When Henry Ford died after World War Ii and left his company in a weakened position, Alfred Sloan told grandson Henry Ford II which General Motors executives to hire to rebuild the Ford Motor Company, which Henry II did.

Controversies

The many authors who have attempted to understand and describe Sloan and General Motors’ success have the advantage of hindsight. It takes some effort to put oneself in Sloan’s shoes and in his era.

Many pages have been written about GM’s resistance to the unions, a position shared by almost all the other automakers. Union organizers at Ford had their heads bashed in. But when the unions staged an illegal sit-down strike in 1937 at GM plants in Flint, Michigan and Anderson, Indiana, Sloan prohibited the use of violence. Management felt a sense of disappointment: General Motors was already paying among the highest wages of any big American manufacturing company, continually adding benefits. GM went on to successfully negotiate generous contracts with the United Auto Workers (UAW).

In any case, Sloan and his colleagues created a company that ultimately employed over 800,000 people, 600,000 of them in the United States. The company put a lot of food on the table and cars in the garage for many families, even more if one includes the thousands of GM dealers and suppliers. General Motors also paid enormous federal, state, and local taxes.

General Motors’ German Opel division supported the German government in the years leading up to World War II. Sloan and his team did not think it was the place of a business to get involved in local politics. When America declared war on Germany, the Nazi’s took control of Opel, which became an important part of the Nazi war machine. After the war, GM somewhat reluctantly took back Opel, which had been severely weakened by the war.

Sloan, like the majority of big business leaders, opposed the New Deal, especially as the government took control of a greater and greater share of the economy. He personally funded organizations to fight FDR’s policies.

However, he was opposed to General Motors as a company getting involved in politics. Only when senior GM executive John Raskob became a national figure in the Democratic party did Sloan come out publicly in favor of Herbert Hoover in the 1932 Presidential election. He did not want the public to think GM was “only a Democrat company,” saying, “I want to sell cars to Republicans, too.”

As Chairman, he and GM President Charles Wilson led GM to support FDR in World War II. Wilson had become President when Sloan’s original successor, William Knudsen, quit GM to run the war production effort. Knudsen showed no favoritism to GM in awarding contracts, echoing Sloan’s objectivity. Charles Wilson later left General Motors to become Eisenhower’s Secretary of Defense.

As General Motors rose to sell over half the cars sold in America, government anti-trust people came after the company. Some wanted to break up GM. The court cases lasted for years, and nothing much came of them. But Sloan was disgusted by the duplicity of the politicians he met and testified in front of. He even went so far as to say he would rather turn the company over to the unions than to the politicians. The national debate about the role of big companies and the role of government regulators in the economy continues to this day. Some would side with Sloan, some would not.

Legacy

For the hundreds – or thousands – of management scholars and academics who have studied Sloan, a big question is, if GM “perfected” management systems, why did the company go into decline at the end of the 20th century? Page after page has been written implying that Sloan’s system had flaws that eventually became apparent.

Our own analysis is that Sloan was a man of his era. He built a company in what was then a growth industry. All of Sloan’s voluminous writings indicate that he understood that the world was always changing. He loved the dynamics of the marketplace and the challenges of competition.

Rather than try to apply Sloan’s policies to the auto industry today, we would rather ask, “What would Alfred Sloan do if he were alive today?”

Our conclusion is that he would be continually studying the facts, finding great people, and adjusting his policies to meet the current situation. Might he have adjusted the committee system to act faster? Might he have been more aggressive in developing and commercializing electric cars, sooner than GM did? Might he have found better ways to work with the unions? Might he even have become a more “conscious capitalist?” Given his never-ending ability to learn, to grow, and to adapt, we think General Motors might have done better in the era leading up to its 2009 bankruptcy had the company found another leader of Sloan’s caliber.

Today, Alfred Sloan is most visible from his philanthropy. In addition to Sloan Kettering, he funded the management school at MIT. (He was always a believer in education for people at all levels in GM, funding the General Motors Institute and many other programs.) The Sloan Foundation, created in the 1930s, today funds everything from scientific research to PBS programs with over $100 million a year in grants from its almost two billion dollars in investments.

No matter how one views and assesses the life and achievements of Alfred P. Sloan, Jr., he will not soon be forgotten by those who lead large, successful enterprises and by those who study the art and science of management.

A Personal Footnote: Life in a General Motors Factory Town in the Company’s Heyday

The time is 1965. The place is Anderson, Indiana, perhaps the largest General Motors factory town outside of Michigan. In a city of about 60,000 people, as many as 27,000 work for the GM parts factories here, Delco-Remy and Guide Lamp. No place on earth has as many people designing, testing, and making automotive electrical systems. No place has as many engineers who understand batteries, ignitions, headlights, and taillights. At 3 PM every afternoon, the shift change whistle goes off and can be heard for miles. When car sales are strong, the factories run three shifts, around the clock. The United Auto Workers (UAW) Union local is one of the largest in the nation. Begun with a sit-down strike in 1937, so intense that the governor of Indiana declared martial law, the UAW builds one of the fanciest buildings in town, their union hall replete with a bowling alley, auditorium, and other amenities.

GM workers, often with both parents working, live side by side with doctors and lawyers, whose incomes are the same (though the lawyers’ wives are more often homemakers). When car sales drop, the newest hires are the first to go, but always get right back in line to try to get on at “the factory.” The city’s economy is strong: business is good for all the restaurants, grocers, and other businesses which depend on the GM employees for their survival and prosperity. Crime is low and divorce rare. The public schools, funded in part by General Motors’ tax payments, are among the best in the state. Dozens of other manufacturing companies in Anderson provide more jobs as they supply General Motors with boxes, copper wire, label printing, and tools.

General Motors brought prosperity to the city; it was life itself. The greatest company on earth would continue to grow and prosper, probably forever, the people of Anderson thought. Residents referred to the company as “Generous Motors.”

Today, Anderson has zero General Motors employees. GM donated about seven million square feet of abandoned factory buildings to the city. GM, which had for decades been the greatest, largest, and most profitable manufacturing company in the world, eventually descends into bankruptcy in 2009. The fine UAW hall is now a Baptist Christian School. Most retirees are in fine shape, with good benefits and retirement packages. But no new jobs are being created.

Anderson survived and lives on, as does General Motors. Both have been reshaped by their history, today into forms almost unrecognizable in 1965.

(Anderson, Indiana is where your writer spent the first eighteen years of his life, during General Motors’ glory days. His grandfather was a skilled laborer for GM, retiring in 1948. His observation of GM led your writer to a lifelong interest in business and business history, the nagging questions being, “What makes companies rise and fall? How does that affect the bigger society?”)

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.