The most important principles of retailing are quite simple:

- Know your customers and the role you play in their lives.

- Know your merchandise and its suppliers.

- Know your competitors.

- Respect each of those, plus your employees.

- Work hard to match the right customer to the right product at the right place, the right price, the right time, in the right quantities. Give them value for their investment of time and money in your store. Do it better than your competitors.

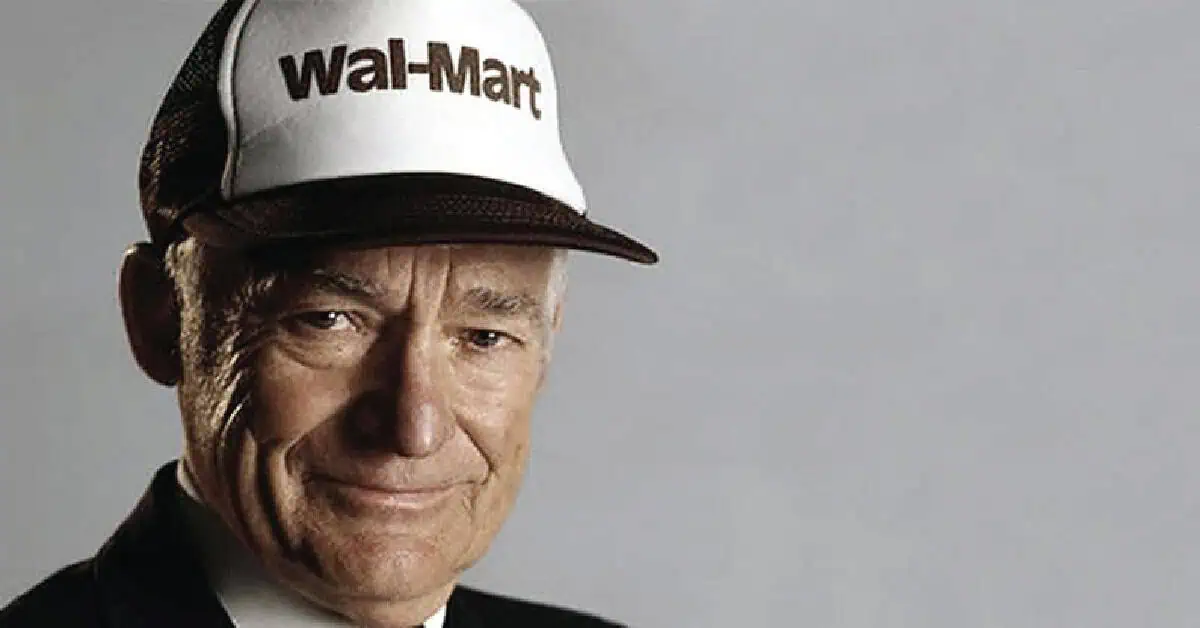

No American has better understood these ideas and put them into practice than Sam Walton and, even after his passing, his company, Walmart. During the time it will take a typical reader to digest this story, Walmart will handle over 600,000 transactions in the United States, with each customer leaving the store satisfied that they got a good deal.

If one had invested $10,000 when Walmart first offered its stock in 1970, it would be worth about $200 million today, plus millions in dividends ($466,000 a year currently).

All of this came about because, in Sam’s own words, “There’s absolutely no limit to what plain, ordinary working people can accomplish if they’re given the opportunity and the encouragement and the incentive to do their best.” Here is the story of Sam Walton and the stores he loved.

Beginnings

Samuel Moore Walton was born March 29, 1918, in Kingfisher, Oklahoma, to his father, Thomas, and mother, Nannia “Nancy” Walton. He was followed three years later by one brother, James, known to all as “Bud.” Father Thomas was first a farmer, then moved around towns in Missouri (Springfield, Marshall, and Shelbina) serving as a banker, a mortgage agent, and a real estate and insurance agent. Hard working and honest, he was above all a trader, ready to negotiate on anything, from cars to mules to farms.

The family was not poor but was not rich by any standards. In the depths of the Great Depression, which hit the “dust bowl” region hard, Thomas had to deliver foreclosure notices to hundreds of farmers. He tried his best to help them retain their self-respect. Growing up in the environment, the two sons learned “the value of a dollar.”

Young Sam showed ambition from an early age. When his mother had a small milk business to earn extra money, Sam milked the cows in the morning and delivered the milk in the afternoons. By the age of seven or eight, he was selling magazine subscriptions door-to-door, as well as raising and selling rabbits and pigeons. By the seventh grade, he had newspaper routes, which he continued all the way through college.

In high school, Sam dated a girl whose father was a very successful insurance salesman, and Sam thought the father “was making all the money in the world.” So he decided he should become an insurance agent, given his proven selling skills.

Sam must have had a great deal of energy, as he was also active at school. In Shelbina, the eighth grader became the youngest Eagle Scout in Missouri history. The family ended up in Columbia, Missouri, where Sam graduated from Hickman High School and was the quarterback on the undefeated and state champion football team and played on the state champion basketball team. He made the honor roll and was elected class president.

Bud Walton later said that even as a youth, Sam excelled at anything he set his mind to, and knew he could excel. Bud attributed these characteristics to their mother. Sam said that his mother always told him to be the best he could, that he took her seriously, and that he always set “extremely high personal goals.” And he loved competition. Later in life, taking on Kmart was like competing with another high school team to him. He said, “It never occurred to me that I might lose.”

Sam stayed in Columbia for college, graduating with a business degree from the University of Missouri in 1940. Continuing in his active ways, he was president of the senior class, his Bible study group, and an ROTC leadership group. In running for these offices, he learned a new trick: he always spoke to people as soon as he saw them, before they spoke to him. He always said hello to strangers and friends alike. Your status or popularity did not matter; Sam knew all the janitors by name. Everyone who ever met Sam Walton liked him.

Sam supported his church, first Methodist and then Presbyterian, his entire life, including teaching high school Sunday school classes. He said, “I don’t know that I was religious, per se, but always felt that the church was important.”

In 1939, Sam’s parents lived next door to Hugh Mattingly, who owned a chain of about sixty dime stores. Sam drilled him with questions about merchandising and retailing, how the industry worked.

Sam paid his own way through college, waiting tables in exchange for food and serving as the head lifeguard at the swimming pool. He continued his paper routes, hiring others to help him, and made $4-5,000 a year (about $100,000 in 2023 money). His supervisor at the newspaper said of Sam, “He did a lot of other things besides deliver newspapers. In fact, he was a little bit scatterbrained at times. He’d have so many things going, he’d almost forget one. But, boy, when he focused on something, that was it.”

Upon graduation, Sam did not have enough money to attend the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania as he had hoped. When recruiters came to campus, he got offers from retailers Sears and J.C. Penney. He accepted the offer from Penney’s, a company renowned for enriching its store managers. (See our American Originals story on James Cash Penney here.)

Sam Walton Becomes a Retailer, Soldier, and Husband

Three days after graduation, on June 3, 1940, Sam reported to work as a management trainee at the J.C. Penney store in downtown Des Moines, Iowa. It was not all smooth sailing: Sam was so focused on serving customers that he sometimes ignored required paperwork. His handwriting was also intelligible to almost everyone. When an auditor from headquarters came to the store and saw his work, he said, “I would fire you if you weren’t such a good salesman.”

Luckily, store manager Duncan Majors liked Sam. Majors had trained more future Penney’s managers than any other Penney’s manager. He, Sam, and the six other managers worked from 6:30 in the morning until 7 or 8 p.m., six days a week. On Sunday, they gathered at Majors’s house, played ping pong or cards, and talked about retailing. At one such meeting, Majors showed the others his annual bonus check for $65,000 ($1.4 million in 2023 money). Founder James Cash Penney often visited stores. When he came to Des Moines, he showed Sam how to wrap a package with the least amount of paper and twine, but still make it look nice. Learning everything he could from Majors and the Penney company, Sam fell in love with retailing, a love he never lost.

In Des Moines, Sam also began a lifelong habit: studying (and respecting) the competition. Always looking for good ideas that he could adapt and apply, he spent every lunch hour in the Sears store and the big Younker Brothers department store, which were at the same downtown intersection. He soon realized that having strong competition was key to the success of any store. Good competitors kept you “on your feet.”

Sam had been with Penney’s for about eighteen months when World War II began to crank up. By early 1942, Sam was eager to go to the front, using his ROTC credentials. But a minor heart irregularity caused him to flunk the physical exam, so he could not serve in combat and had to wait to be called for non-combat service.

This put Sam “into a funk,” so he quit Penney’s and drifted around for a while before taking a job at a DuPont gunpowder plant in Pryor, Oklahoma, near Tulsa. He lived in nearby Claremore. There, one night in a bowling alley, he met the vivacious Helen Robson. They were soon dating and Sam fell in love with her (and her family) right away. Helen was not only athletic, but she had a college business degree, unusual for a woman at the time. Sam described her as, “pretty, smart, educated, ambitious, opinionated, and strong-willed.”

As soon as Sam fell in love, he got called up by the military. He became a second lieutenant, then became a captain, overseeing security at aircraft factories and POW camps around the United States. (His younger brother, Bud, was a bomber pilot flying off of aircraft carriers in the South Pacific.)

Sam and Helen were married on Valentine’s Day, 1943. While he was still in the military, they moved sixteen times in two years. Their last station was in Salt Lake City, where Sam went to the library and read every book on retailing they had. He spent his off-duty hours studying the big Salt Lake City department store ZCMI, owned by the Mormons. Founded in 1868 by Brigham Young, Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution was one of the oldest department stores in America.

Helen’s father, L.S. Robson, was a very successful lawyer, banker, and rancher. Over the years, Sam learned a great deal from him about finance and law, and how to run a business. Mr. Robson was always supportive of everything Sam did. At the same time, when Sam and Helen later had to pick where to live, Helen ruled out Claremore, saying she did not want to be married to a man who would mainly be known as her father’s son-in-law; she wanted an independent man.

When released from the military in 1945, Sam was eager to return to retailing. He wanted to go into the department store business, which dominated American non-food retailing at the time.

A Store of His Own

It’s worthwhile to understand the retail context of the time. American had hundreds of thousands of independent stores selling products of every description. The nation had seen the rise of big chains, led by grocers the Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (the “A&P”), Kroger, and Safeway. In non-food or “general merchandise,” there were three major types of stores.

Dominating in the emerging giant urban centers were the department stores, including Macy’s in New York, Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia, Marshall Field’s in Chicago, and Hudson’s in Detroit. Every city had several such giant stores, as big as two million square feet at Macy’s and Field’s. Many were still family owned, while others had joined big groups including Federated Department Stores, Allied Stores, May Department Stores, and Associated Dry Goods. These stores carried everything and were the most prestigious stores in each city. Smaller independent department stores, often selling to lower-income customers, also dotted the cities.

The second component of general merchandise retailing were the more recent “national chains.” Arising from catalogs selling to farmers, Sears and Montgomery Ward, both based in Chicago, built new stores focusing on hard goods from coast to coast in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s. In soft goods, Penney’s built a huge national chain.

The third component was the pervasive dime store, also known as variety stores, “five and tens,” or “the syndicates.” Led by the giant F.W. Woolworth company, which had in 1913 built the tallest building in the world for its New York headquarters, other chains included W.T. Grant, S.S. Kresge, Newberry’s, McCrory’s, G.C. Murphy, and others. Known for their long lunch counters and serving “hoagie” submarine sandwiches, the dime stores carried every type of small, affordable item—from school tablets to pots and pans to underwear, even goldfish. Many baby boomer women bought their first lipstick at Woolworth’s. The stores’ merchandise mix might resemble that of a chain like Dollar General today. Every region of the country also had regional dime store chains like Danner’s in Indiana and Sterling in Arkansas, as well as independent stores. In 1939, America contained 10,000 independent dime stores and 6,000 chain dime stores. You could not turn anywhere, whether in Manhattan or the smallest town, without seeing a dime store.

In this context, a leading company was Butler Brothers, a wholesaler serving mainly dime stores, which operated out of huge warehouses along the Chicago River. In order to develop more wholesale business, Butler Brothers supported a national “franchised” chain of independently owned dime stores under the name Ben Franklin stores, competing with Woolworth’s and the like. Butler Brothers also similarly franchised a chain of small department stores.

And it was one of those Butler Brothers department store franchises that Sam Walton had his eye on, in St. Louis. He and his college roommate began to raise the money to finance the venture. But Helen put her foot down. After moving sixteen times in two years, she wanted to settle down, and had zero interest in living in a big city. She said, “A town of 10,000 is big enough for me.” In addition, her family had seen partnerships go sour, so she insisted Sam go out on his own, without a co-owner.

So Sam asked the Butler Brothers people what else they had available for him. They had the “perfect spot”—a Ben Franklin store in the cotton and railroad town of Newport, Arkansas, population 7,000. The St. Louis owner was willing to sell the store for $25,000. Sam jumped at the opportunity, only later realizing that Butler Brothers had found ”a sucker” to take over the money-losing 5,000-square foot store. With $5,000 of his own money and $20,000 borrowed from his father-in-law, Sam Walton took over the Newport Ben Franklin on September 1, 1945. He was twenty-seven years old.

As usual, Sam set a goal for himself and his store: to be the best, most profitable variety store in Arkansas within five years. He said, “Set that as a goal and see if you can achieve it. If it doesn’t work, you’ve had fun trying.” He also felt it was a blessing to be so green and ignorant, because it forced him to come up with another lifelong rule, “You can learn from everybody.”

First, he learned a system of accounting from Butler Brothers, a system he continued to use even through his first five or six Walmarts seventeen years later. More importantly, he learned from the Sterling chain dime store across the street, which was well-managed and generated $150,000 a year in sales compared to the Ben Franklin’s $72,000. He was in the Sterling store every day, checking pricing and merchandise displays, ever learning. Sam’s brother Bud soon joined him at the Newport store.

In his efforts to generate excitement, Sam began to seek new sources of merchandise, better values for his customers, wherever he could find them. Butler Brothers required that the Ben Franklin stores buy at least 80 percent of their goods from Butler Brothers, including their markup. Sam kind of ignored that, beginning his long history of being a maverick, often a rule-breaker. He found a source of less expensive goods, mainly underwear and shirts, in Tennessee. After his store closed for the day, he would drive to Tennessee, pulling a homemade trailer. He took backroads to avoid weighing scales when he knew he was over the government weight limits, and crossed the Mississippi River on a ferry each way.

Sam began to realize how much more business he could do by beating the competition on price. He found a New York merchandise broker who would sell him panties for $2 a dozen compared with Butler Brothers’ price of $2.50. He put them on sale in his store at four for a dollar when the competition, and the other Ben Franklin stores, sold them at three for a dollar.

Sam looked everywhere, talked to everyone, studied the competition, and his store began to prosper. In two-and-a-half years, he had paid back the $20,000 to L.S. Robson. By the third year of his ownership, the Newport Ben Franklin was doing $175,000 a year, and very profitable.

Sam became president of the Newport Chamber of Commerce. He and Helen loved the town, and soon had three sons and a daughter.

One day, an auditor from the J.C. Penney company came to Newport to inspect their store, which was managed by one of Sam’s friends. The manager said, “We have a good competitor here in town who has done well with his Ben Franklin store.” It turns out the auditor was the same guy who had come to Des Moines and threatened to fire Sam. In Newport, he said, “It can’t be the same Sam Walton I met in Des Moines, that fellow could not have amounted to anything.”

Sam’s store got up to $250,000 a year in revenue, making a profit of $30-40,000 (about $500,000 in 2023 money).

But as good a learner as Sam was, he had more to learn. He had signed a lease on the Newport store that had no renewal options in it. So when the lease ended, he had no power. The building owner refused to renew the lease, as he wanted to buy the store to give his son something to do. Sam and Helen were heartbroken. Sam considered this the low point of his business life, but he learned a lot about leases and contracts. He sold the store at a $50,000 profit and had to figure out what to do next.

Bentonville and a Chain of Ben Franklins

As Sam has said, he “drove Butler Brothers crazy” with his rule breaking. Nevertheless, he bought a lot of goods from them and was one of their best operators, so the door was still open for him to get another Ben Franklin franchise. He looked at several cities, but picked the smallest, little Bentonville, Arkansas, population 3,000. Bentonville was closer to Helen’s family in Oklahoma. Just as important, it was close to good quail hunting in Missouri, Arkansas, Kansas, and Oklahoma, allowing Sam his favorite hobby in four separate hunting seasons. Sam trained his own hunting dogs and treated them like family. (His other primary recreation was tennis, which he played aggressively all his life; golf was way too slow for him.)

Sam bought an independent dime store. In July of 1950, he re-opened the store as Walton’s Five and Dime. While he used the Walton’s name, he was still a Ben Franklin franchisee. While dime stores traditionally had clerks and registers scattered throughout the store, Sam caught on to the emerging idea of “self-service,” with banks of registers at the front of the store near the exits. The Bentonville store was the first self-service dime store in the eight-state region. The store had done just $32,000 in sales, but quickly hit $95,000 and began to grow.

One of his first clerks in the store, Inez Threet, said, “I guess Mr. Walton just had a personality that drew people in. He would yell at you from a block away . . . he brought in business by his being so friendly.”

Sam, always full of ambitious goals, began to look for towns in which he could operate successfully. He soon opened a store in nearby Fayetteville, and then Versailles, Missouri, population 2,000. He opened a store in Ruskin Heights outside Kansas City and did $350,000 a year. He tried to put a store near Little Rock, but the deal fell through. As he expanded the chain, be borrowed more and more, from every bank in sight. He was deep in debt, which he hated, but his drive to expand kept him borrowing.

Sam, known as a terrible driver, spent hours and days driving around to his expanding little chain. Always impatient, he decided he needed to learn to fly and buy his own airplane. This terrified his ex-bomber pilot brother Bud, who refused to fly with him for the first couple of years. One of Sam’s favorite adventures was flying over a new town, tilting the plane on its side, counting the cars in the Kmart parking lot, and picking the best site for a new Walton store. Over his career, Sam Walton owned nineteen different airplanes, starting with the smallest two-seater with one engine. One time his engine died, and he had to coast back to the airport. When jets came along, he resisted buying one, and did not like it much because it was too fast to use for picking sites. Sam later chose the first four or five hundred Walmart locations from the cockpits of his little planes.

From that small start in Bentonville, over the next twelve years Sam Walton developed the largest group of Ben Franklin franchised stores in the country, about fifteen of them. While his best store did $2 million a year, most of the stores generated $200-300,000.

Sam was a “mover and shaker” in Bentonville and had to be one of the wealthiest people in town. He, Helen, and the family lived in a beautiful home designed by the famous architect E. Fay Jones, a former apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright. Most men would have sat back and enjoyed their laurels. Not Sam Walton. He was just having too much fun. He had agreed with Helen to stop expanding and slow down, but later had to renege on that promise.

The Birth of Walmart

Sam Walton never stopped going to retail stores, wherever he traveled. He never stopped watching trends and innovations in the industry. By the start of the 1960s, the hottest concept in retailing was the discount store. Beginning in the late 1940s, in New England, with a store called Ann & Hope, the concept soon spread across the northeast. The idea was to lease a cheap building, add very cheap display fixtures, buy goods from the cheapest suppliers, “pile them high and sell them low.” No service, no frills. These stores took little capital to build and open, so many fly-by-night operators jumped on the trend.

By 1962, there were over 2,000 such discount stores in America’s largest cities, over 300 in the New York area alone (which Sam visited on his many buying trips to the city). The business press called the largest company, E. J. Korvette’s, “the next Sears” (Sears was at the time the largest retailer in the world). The second largest company, Interstate Department Stores, which had operated a few small city department stores, opened under the names Topps and White Front on both coasts. Other large players included Arlan’s, Zayre, and Two Guys from Harrison. Alongside them were another three hundred operators of two or more discount stores in every state.

Sam could see the writing on the wall: the dime store industry would be hit hard by this new concept. There was no way he was going to become a “sitting duck.” As before, Walton first “did his homework.” He visited the headquarters of all the important companies and asked to see their president. He’d walk in, say, “Hi, my name is Sam Walton, from Arkansas, and I would like to meet Mr. So-and-so.” Usually, they were curious about the small-town “hick” and answered his multitude of questions. Sam took prodigious notes, at first on yellow legal tablets but later on a pocket recorder.

Among the many companies he studied was Fed-Mart, a membership discount store founded by innovator Sol Price in San Diego, which was the fifteenth-largest discount chain at the time. Sol and Sam became good friends and often compared notes.

Virtually all of these stores were in larger cities, but Sam understood the unserved potential of smaller communities.

Sam determined that he had to get into the discount store game if he were to survive, let alone grow his little retail company. His first step was to visit Butler Brothers’ headquarters in Chicago, where he tried to convince top management to back his idea of small-town discount stores. Butler Brothers and their Ben Franklin stores had good systems in place, they knew where to source merchandise, and they were in many smaller towns. The Butler Brothers people thought he was crazy and essentially told him to get lost. Undeterred, he knew he had to go it alone.

Sam began to plan his first discount store. His own credit was not strong enough to borrow all the money needed, so he also relied on Helen’s credit. They borrowed against their home and everything they owned to launch the first store.

He considered several names before deciding on Wal-Mart (the hyphen was dropped years later) because it used fewer letters than other names, saving money on the sign, and he liked what Sol Price had done with Fed-Mart.

While Sam was working away on his idea, other far larger companies entered the discount store fray. In the spring of 1962, the giant S.S. Kresge dime store chain of Detroit, under the leadership of Harry Cunningham, opened its first two Kmart stores. Kresge built new stores as fast as possible, and by 1968 Kmart was the biggest discount store chain by far, with over a billion dollars in annual revenues. In May, Dayton’s department store of Minneapolis opened the first Target store, with the idea of offering customers a more polished, “upscale” version of the discount store. In June, the biggest dime store company, F.W. Woolworth, opened its first Woolco discount store.

On July 2, 1962, Sam opened the first Walmart in Rogers, Arkansas, close to his Bentonville base. The store opened with signs proclaiming two key principles: “We Sell for Less” and “Satisfaction Guaranteed.”

The Rogers store was a modest success, doing a million dollars in sales in its first year, but Sam had his foot in the door.

Sam soon added a store in the larger Springdale market, then another in the smaller city of Harrison. Another retailer from Missouri, David Glass, visited the Harrison store’s grand opening. Sam had piled up discounted watermelons outside the store. He also had donkey rides for the kids. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a very hot day and the watermelons popped and spread their juice all over the parking lot, where it combined with massive donkey droppings. Customers tracked the stinky soup into the store. Glass said, “It was one of the worst stores I had ever seen.”

But Sam persisted, and kept borrowing money, straining the nerves of bankers across the region. He kept flying, building stores outward from his home base in northwestern Arkansas. Soon enough, he entered Missouri and Oklahoma.

Building the Chain; Sam’s Methods

Like all highly successful retailers, Sam Walton was a “numbers guy.” He knew the sales and profits of every department in every store, keeping ledger sheets with this year and last year numbers by hand. He soon realized that in order to grow his company, he needed better ways to keep up with their results. The company had to figure out exactly which items to carry, in which stores, in what quantities, and at what times of the year. This led him to invest heavily in information systems that were more advanced than his competitors.

But Sam was also frugal, to put it mildly. So every time one of his associates asked for faster and better computers, he fought them on it at first, and demanded they prove why they needed to spend the money. When he and his colleagues traveled, they stayed at the Days Inn and other such motels, two to a room, sometimes more. His “headquarters” was a shabby operation with sloping floors upstairs above other stores in downtown Bentonville. Headquarters staff numbered three or four, including Sam. He had learned long ago that if you kept your expenses low, you had an extra advantage over your competitors. Rather than pocketing the savings as the owner of the company, Sam passed the savings along to his customers, increasing his market share and competitive power.

Sam applied these same philosophies to purchasing merchandise. He believed that Walmart was the agent of his customers when it came to dealing with the giant manufacturing companies like Procter & Gamble and Coca-Cola. Long accustomed to buying lunch for retail buyers, offering special advertising allowances instead of lower prices, and printing millions of coupons, the big companies were not used to Sam, who said, “I do not want any of that. I only want the very best low price you can give me and still make a good quality product and still make money for yourself.” For years, the big producers could ignore the little guy from Arkansas, but over time had to cave. Walmart will not allow any vendor to even buy lunch for a Walmart buyer. And today Walmart is the largest customer for thousands of American companies, many of whom like Procter and Gamble have prospered and become more efficient as a result.

Sam soon realized he could not efficiently supply his stores from his small warehouse in Arkansas. Over time the company invested millions in distribution centers, each one serving stores within a 350-mile radius, a day’s drive. Instead of having every supplier deliver goods to him using hundreds of trucking companies, Walmart began to “back haul”—picking up goods at factories near the stores they had just delivered goods to. Today the management of the flow of goods is called the “supply chain” or “logistics.” When Sam later met Federal Express founder Fred Smith, he told Fred that he (Sam) was a pretty good retailer but a better logistician.

Sam also came to realize that communication was key to success. Unable to visit every one of his growing number of stores, he added more and more sophisticated communication systems, including a satellite-based television system that reached every store. One day, Sam got on the system and reached out to every store employee, asking them to make eye contact and say hello to every customer. Another Walmart hallmark was the Saturday morning meeting in Bentonville, when all the key managers in the company gathered to discuss what was going wrong and what was going right in the stores. If there was a problem, they would make phone calls during the meeting to get it fixed, eliminating debate and delay. And Sam himself came to work at 3 or 4 a.m. on those days, to study all the company’s weekly numbers in preparation for the morning meeting.

In his efforts to “stay in touch” with the business, Sam would ride along with one of his truck drivers or take donuts and coffee to the drivers’ break room. There, he could inquire about how things were going out in the stores, which ones seemed well run and which ones were not. None of his thousands of employees were strangers to “Mr. Sam,” as everyone called him.

While Sam always compensated his key managers well, over time he came to realize that he needed to spread the wealth further, with Helen’s urging. He added profit-sharing and discount stock purchase programs for virtually all employees, following in the footsteps of J. C. Penney and Sears. Early store managers and even secretaries became multi-millionaires as the company (and its stock price) grew.

The man was full of ideas, which sometimes drove his people crazy. Sam prided himself on being unpredictable. He tried to get his pilots to count inventory in the stores when they flew him to a city, but that idea never flew. Against much pushback in the organization, he convinced the company to have greeters at the stores.

Believing a sense of humor and play had a role in leadership, Sam made national headlines in 1984 by dancing in a hula skirt on Wall Street when the company beat profit goals and he lost a bet. Unlike most companies’ dry, legalistic annual stockholders’ meetings, Walmart’s meetings became big parties and celebrations.

Obsessed with saving his customers money, always learning from other retailers, and forever humble and friendly, Sam kept visiting stores and meeting industry leaders. At one point, he met with the head of the national association of discount stores. The man said he would give small-town Sam ten minutes. Sam showed the man his profit and loss statements for each of his stores, and every expense item. The man said he could not believe how profitable Sam’s small-town stores were. Two and a half hours later, Sam emerged with pages full of notes and a head full of new ideas.

Sam later claimed that he had spent more time in Kmart stores than any Kmart executive, a claim that would be hard to refute. Unlike many businesspeople, Sam never focused on the weaknesses or problems of his competitors, he only looked to see what they were doing better than Walmart. Ego had no place in Sam Walton’s world. Getting better every day was everything to the man.

Sam’s driven curiosity did not stop at the borders of the United States or of the retail industry. As he prospered, he visited every store he could find in Japan, Korea, all over Europe, Australia, South America, and elsewhere. He studied management thinkers and textbooks, drawing ideas from people like W. Edwards Deming, the man who helped Japan master quality production methods.

While this story may seem to imply that Walmart was a one-man show, this could not be further from the truth. From the very beginning, Sam met the best retailers in the country and tried to get them to join him. David Glass, the retailer who complained about the donkeys and watermelons years earlier, was eventually persuaded to join the company, and succeeded Sam as the chief executive officer in 1988.

For years, the major discount store chains ignored Sam as he opened stores in towns of two to twenty thousand population, places few others were looking. And, over time, the fly-by-night operators fell by the wayside, in bankruptcy after bankruptcy as a traditional “industry shakeout” took place.

The Explosion of the Chain

A most unusual aspect of the Waltons was that they believed in family ownership. Way back in 1953, following a model created by Helen’s father, Sam gave all his shares in the company to a family corporation, of which he and Helen owned 20 percent and each of his four children owned 20 percent. This structure led to a “community of shared interests” by the family and eliminated issues of big inheritance taxes years later. Sam continuously worried that his kids and grandkids would get into fights like rich kids often do, or that they would sell off the company. Personally, Sam had little use for money except to build more stores and worked hard to keep the family humble. The children all worked in the stores and toured the country with Sam visiting stores.

Sam and Helen hated it when the press later labelled him the world’s richest man, saying, “It’s just paper.” When magazine writers were amazed that he drove an old pickup truck, he said, “What am I supposed to haul my dogs around in, a Rolls-Royce?”

By 1969, Sam had tapped out every bank he could, as he kept borrowing and borrowing to build new stores. His family was deep in debt. Despite resistance from Helen, who wanted to keep the business and the family financial affairs private, he decided he had to sell some stock to the public in order to raise capital and pay down his debts.

On October 1, 1970, Walmart, consisting of 32 dime stores and Walmart stores, went public. Two years later the stock was listed on the New York Stock Exchange. The initial offering was for 300,000 shares at $16.50 per share. Before the stock offering, Sam’s family had owned 75 percent of the company and his brother Bud owned 15 percent. After the sale, Sam, Helen, and their children owned 61 percent. As of 2023, the family still owns an amazing 46 percent of the company’s shares, worth about $200 billion.

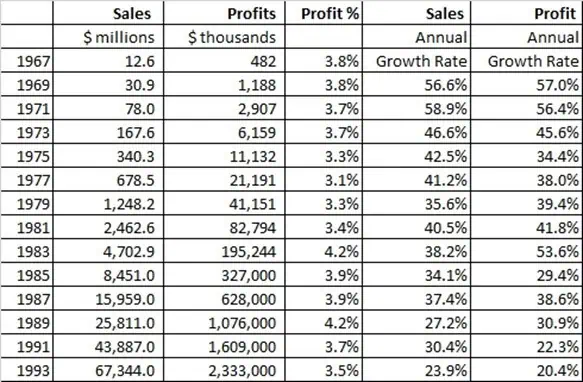

Ever curious, ever humble, Sam Walton kept pressing his foot on the accelerator. Using the methods described in the preceding paragraphs, the numbers tell the story:

As Sam continued watching trends, three new developments were critical to these astounding growth numbers.

First, Sam stayed in touch with his old friend Sol Price in San Diego, who had sold his Fed-Mart chain to a German company which ruined it. Like Sam, Sol was committed to bringing his customers the best deal possible. In the late 1970s, he opened the first Price Club, a giant members-only warehouse or wholesale club. The idea was to sell products to independent and small merchants at the same low prices that the giant chains could get. Over time, Sol opened his stores to the general public, but they still had to buy an annual membership. The stores combined food sold in bulk quantities along with supplies and equipment for hotels, restaurants, and small businesses. After an initial stumble, the initial San Diego store was doing one of the highest revenues of any store in the nation.

Sam and Helen had dinner with Sol and his wife, and Sam as usual learned everything there was to know about the Price Club. Soon after, Sam called Sol to tell him he was going to open his own wholesale clubs, starting in Oklahoma and Texas. Sol was not surprised. (Later, one of Sol’s key associates, Jim Sinegal, left the Price Club to start Costco in Seattle, which later acquired the Price Club chain.)

The first Sam’s Club opened on April 7, 1983, near Oklahoma City. Sam loved the new business; it was like starting again for him. He again pressed the peddle to the metal and soon had more stores in operation than Sol Price did. This venture further boosted the company’s total sales.

The second big move, and the most important for the company, was the development of the Supercenter, which combined the traditional non-food discount store with a full grocery store. This was a very risky move on Sam’s part.

Many big discount chains and others had tried to combine food with non-food (“general merchandise”). Kmart tried a partnership with a grocery chain in Detroit, which did not work out. St. Louis’s Schnuck’s grocery chain dabbled in a combination deal with Walgreen’s that did not work out. Albertson’s grocery stores of Boise had a partnership with Skagg’s drugstores that achieved temporary success, but then died. Each learned that food is a very different business from general merchandise, with lower profit margins, faster turning items, perishables that could go bad and cost you a lot of money, and requiring expensive refrigerators and freezers. A store’s plumbing and air-conditioning systems had to be completely different.

In Europe, the French company Carrefour had great success with super-giant combination stores called Hypermarkets. They spread around the world and were copied in Europe and abroad. Sam studied the Carrefour stores in Brazil.

In this context, there were three regional firms that had successfully integrated food and general merchandise: Fred Meyer in Portland, Oregon; Meijer’s of Grand Rapids, Michigan; and Schwegmann’s of New Orleans. Each of these companies had developed stores that offered true one-stop shopping, and their stores were generating very high sales per store. Sam studied them hard. He also learned a great deal from selling food in Sam’s Clubs.

He first tried his own version of the European hypermarket, opening four Hypermart USA stores. They were disappointing, too large and not profitable. This was one of several mistakes that Sam made, owned up to, and learned from. He then settled on a smaller version, which he called Walmart Supercenters. The first one opened in 1988 in Missouri. In the following years, the company gradually replaced most of their old discount stores with new Supercenters. Today the American Walmart Supercenter operation is the largest single retail operation in the world by revenues, with 3,572 stores (compared with only 364 remaining Walmart discount stores). Food represents 58.8 percent of Walmart sales in the United States, making it by far the nation’s (and world’s) largest grocer.

The company’s third major evolution was entry into international markets. This began with a joint venture in Mexico City in 1991. As experienced by other American retailers, the road abroad is not easy, as companies have to adjust to different cultures and work and shopping habits. Over time, the company entered and left the United Kingdom, Germany, and Korea. But in some countries, the company has been a major success. Walmart later took full control of the Mexican joint venture, and today has 2,862 wholesale clubs and Supercenters in Mexico, 882 stores in Central America, 402 in Canada, 392 in Chile, 375 in Africa, 365 in China, and 28 in India.

Each of these three major initiatives was initiated by Sam Walton, and built upon by his successors, who have also more recently moved aggressively into online shopping with Walmart.com and other concepts around the globe.

Walmart After Sam

On April 5, 1992, Sam Walton died of bone cancer at the age of 74. According to all reports, he was tracking store results up until the day he died. Helen Robson Walton passed away fifteen years later.

At the time of his death, Sam Walton and his team had built a $50 billion company starting from virtually nothing. Since his death, due to the principles Sam believed in, his successors have posted an even more remarkable record, building more Supercenters and Sam’s Clubs and expanding overseas and online. The company has also expanded the benefits offered to employees, including affordable prescriptions and education benefits. As a conservationist, no company has more to gain from using less energy in its stores and trucks and has led the industry in such efforts.

By 1992, Walmart had passed Sears and Kmart to become America’s largest retailer. In 1994, it became America’s fourth-largest company by revenues, behind General Motors, Ford, and ExxonMobil. By 2001, it was the largest company in the world, holding that position for 18 of the last 22 years, only falling behind big oil companies when oil prices spiked. In 2017, Walmart became the first company in world history to generate a half trillion dollars in annual sales. In 2022, the figure was $605.9 billion. With over two million employees, it is the world’s largest private employer.

The enormity of the company is hard to comprehend. Their retail space totals one billion square feet—all of which must be kept spotless every day. The company has over one hundred million square feet in hundreds of warehouses and distribution centers scattered around the globe. The typical Supercenter carries 120-140,000 different items. Customers move through the registers transacting about ten billion sales per year. An estimated 64 percent of all Americans shop Walmart every month, and a greater number shop there occasionally.

Sam Walton always said that the Walmart story is one of ordinary people achieving extraordinary things. As to Sam himself, we can only view him as one of the most extraordinary ordinary business leaders in American history.

“I always told my mother and dad that I was going to marry someone who had that special energy and drive, that desire to be a success. I certainly found what I was looking for, but now I laugh sometimes and say maybe I overshot a little.” —Helen Robson Walton

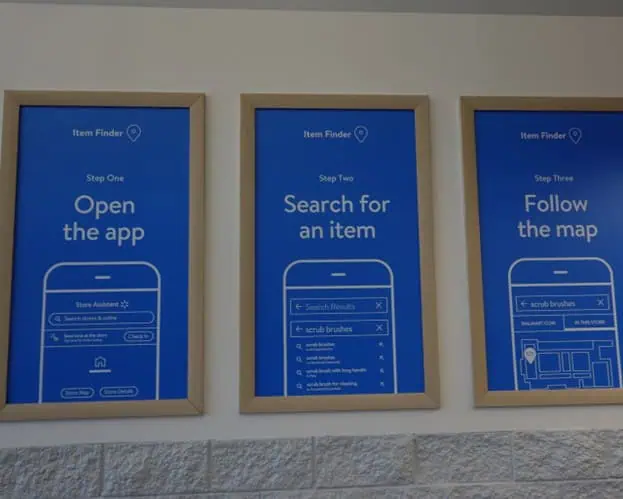

Here are some photos taken of Walmart stores in Tyler, Texas, in October 2023, demonstrating the array of merchandise on the company’s shelves. A long way from donkey dung and exploding watermelons!

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.