Why Welfare Has Marriage Penalties

Welfare has marriage penalties because the eligibility threshold for programs does not account for both adults’ ability to earn money in a family unit. The eligibility threshold adjusts slightly higher based on larger family size, but it makes no distinction between income-earning adults and children (unlike the federal tax code, which allows married couples to file jointly at different marginal tax thresholds than single couples). The result is that one working-class adult will qualify for a host of benefits, but a family where two working-class adults’ incomes are both counted will not qualify for any benefits.

Programs usually only count income toward eligibility when the adults are biologically related to the children in the household. The live-in boyfriend—a housing situation that places children at far higher risk of child abuse—is not counted toward eligibility. This system, on paper, penalizes both biological parents residing with their joint children. In practice, the system is more of a marriage penalty than a broad penalty on biological parents both living with their children, because cohabiting joint biological parents can misrepresent their living situation to welfare authorities; authorities have little ability to verify cohabitation status without welfare officials showing up unannounced at peoples’ homes (which is bad public policy). Studies show that a sizable portion of welfare recipients in many large federal programs, such as food stamps, are misrepresenting their cohabiting status to authorities.

Yet married parents are unable to hide their marriage, and county welfare officials can easily access marriage databases. Thus, welfare has explicit penalties against co-parenting biological parents and implicit, or in-practice, penalties against marriage.

Methodology

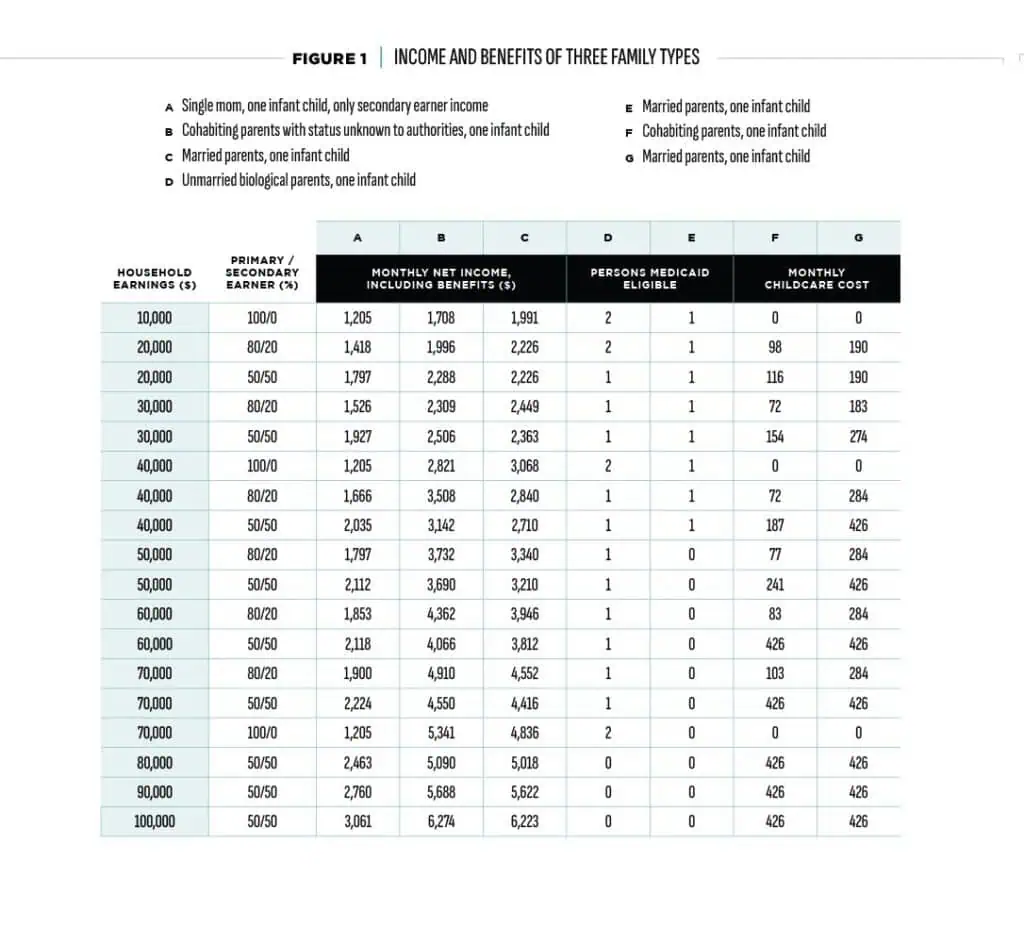

To assess Mississippi’s marriage penalties, the Urban Institute’s Net Income Change Calculator (NICC) was used to compare the taxes and benefits of a family constituting a married couple and their infant child to an unmarried couple with one infant child at the same income levels. The unmarried couple is assumed to consist of two biological parents where the woman is not accurately representing the couple’s cohabitation status to welfare authorities (which is, again, astonishingly common) or two adults where only one is the biological parent of the child.

Calculations with larger family sizes will typically show even larger marriage penalties at higher income levels, but calculations with only one infant child are particularly important because studies show most out-of-wedlock births are to parents who are living together or romantically involved at the time of the birth of their child. Yet because of the instability of cohabitation, most of these relationships eventually fall apart while the child is still young. This usually disconnects the father from the child, leading to a host of economic and social problems.

Among a handful of assumptions made to model family income and benefits, two relatively material assumptions are made: (1) that full-time childcare in Mississippi costs $426 per month for a young child or infant—according to the Economic Policy Institute, which places Mississippi on the lower end of childcare costs in the nation—and (2) that rent costs $950 per month.

As you see below, the analysis looks at combined household incomes of $10,000 to $100,000, at increments of $10,000. At every increment up to $70,000, a separate analysis models the marriage penalty if one parent contributes only 20 percent of household income because that parent works part-time. Here, childcare costs are assumed to be two-thirds of the original cost, or $284 per month.

It is arguable whether these numbers are the best representation of reality, and average costs will vary within different regions of the state—especially based on population density. This is certainly true for the rent assumption of $950 per month. Yet increasing or decreasing rent does little to change the overall results or analysis. Generally, higher living costs mean there is a higher marriage penalty. Similarly, when assessing the childcare cost to a couple with one adult working part-time, assuming a smaller childcare cost will generally shift the marriage penalty for that family by the difference between the originally estimated $284 per month and the new lower estimate.

It is also the case that the NICC doesn’t compute the financial benefit of receiving subsidized medical insurance but only assesses the number of family members who qualify for Medicaid under Mississippi’s program. This understates the dollar value of the marriage penalty in this analysis, although we can see roughly how Medicaid also penalizes married couples.

Finally, the financial situation of a single mother with no other adult income and her infant was analyzed at every income level.

Analysis of Mississippi’s Marriage Penalties

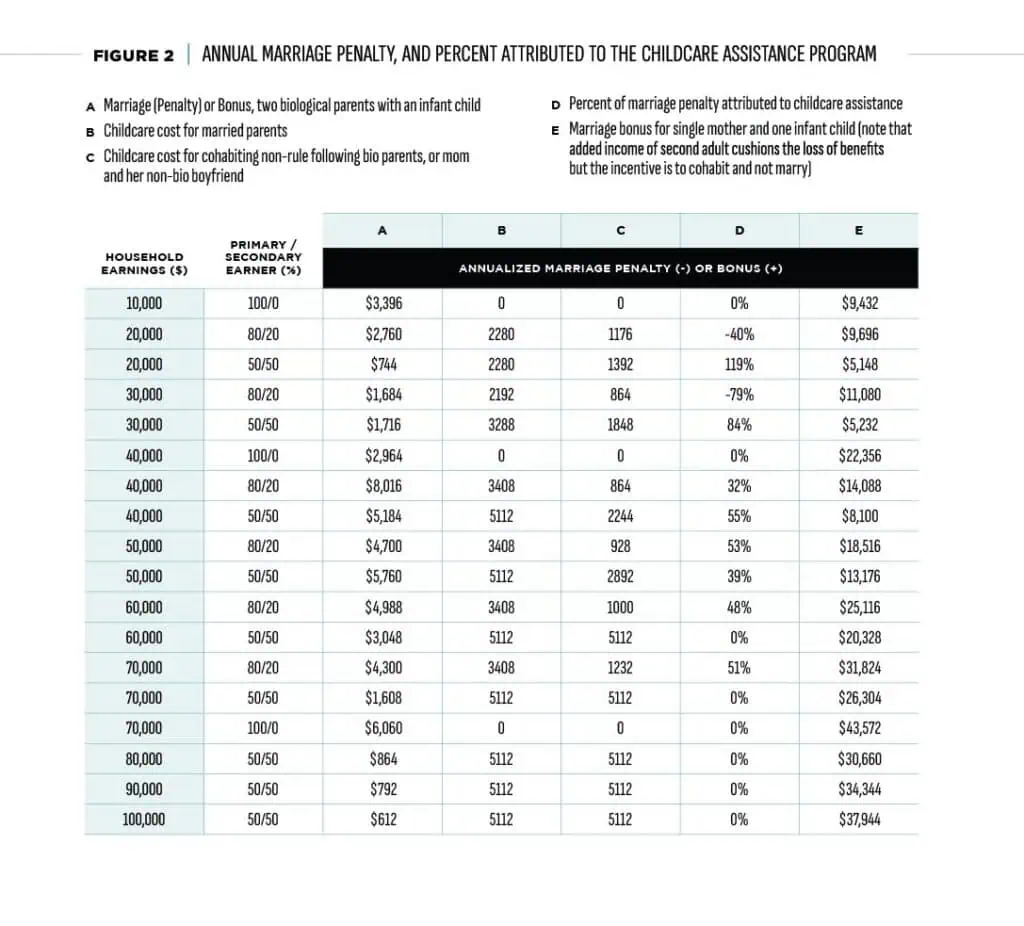

Like most states, Mississippi’s marriage penalties are concentrated in the childcare subsidy. At income levels common for young working-class couples, this subsidy makes up about 50 percent of the overall marriage penalty, excluding Medicaid marriage penalties.

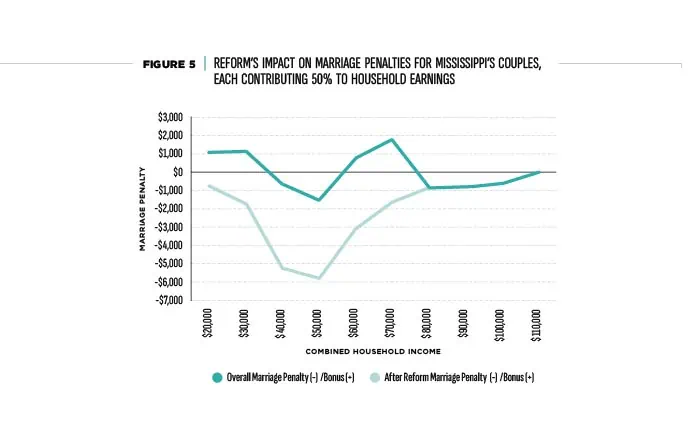

Broadly, the analysis finds marriage penalties at all income levels until both the mother and father individually make at least $40,000 per year, making them ineligible to receive childcare assistance (and most other welfare programs). These penalties are most consequential when both adults earn relatively the same and have incomes at or just below the individual cutoff for eligibility (about $40,000 in Mississippi). This is concerning because most working-class young adults, at prime age for family formation, are in this range—especially for someone who hasn’t earned a four-year degree.

In real life, families may make other decisions than those considered in our table. Starting with the situation of one spouse or biological parent who is working part-time or has lower earnings power, it is clearly not economical for both spouses to work after a certain point if married—here, the couple has to pay the full, unsubsidized price for part-time childcare, and this reduces the benefit to the family of the second income. On top of this, most families will prefer in-home care for nonmonetary reasons. The broad problem, though, is that couples who are not married can theoretically continue the part-time work of the second “spouse,” receive subsidized or even completely covered childcare, and thus benefit financially relative to the married couple. The married couple where one spouse could work part-time gets shortchanged from a monetary perspective, though it is likely that in the real world many of these families prefer to have one spouse stay home with their young children.

As for the single mother, her marriage bonus via adding another adult’s income—often a male with higher earning power—is sharply reduced by the loss of benefits. The single mother could also cohabit with this other adult and receive the benefit of an extra income without losing benefits. Our analysis doesn’t go this far or attempt to quantify this mathematically. But again, the system clearly penalizes married couples compared to other arrangements, though there are certainly other long-term benefits to marriage beyond the initial financial hit of losing benefits.

What is clear is that the system carries the strongest disincentives to marriage when two adults, who have recently had a child together, have relatively equal earning power. Such a setup is incredibly likely today, especially because working-class women’s earnings are often commensurate with or even outpacing earnings in working-class industries dominated by men.

According to the NICC’s calculations, marriage penalties are extremely high for these equal-earning couples at combined parental earnings of $40,000 to $70,000 per year. These marriage penalties in total—of which childcare subsidies make up about 50 percent—reduce household incomes by about 10 percent. Again, this analysis does not count Medicaid marriage penalties, which means actual penalties are even higher.

Either way, this means that marriage penalties in Mississippi permeate the working class and risk reaching into the middle class. A large proportion of young persons at ripe age for family formation and childbearing are especially impacted. The nationwide median salary for 25- to 34-year-olds is $48,000 per year, and those without a four-year college degree—still a large portion of younger Americans—have median incomes of $42,000 or less. The median income of a recent high school graduate with no college degree is even lower in Mississippi. Basically, the entire Mississippi working class is subject to large marriage penalties, especially when both biological parents have similar earnings power.

Mississippi Childcare Subsidy Specifics

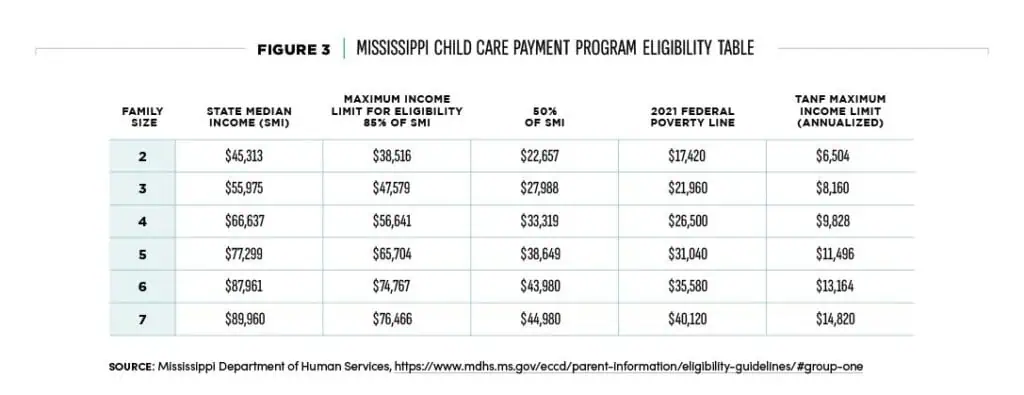

The Mississippi Child Care Payment Program (CCPP) is federally funded (via a Temporary Assistance for Needy Families [TANF] block grant) but administered by the state. Unlike states such as California and Minnesota, Mississippi (along with most southern states) has not supplemented federal funding to increase funding to its childcare program. Because of this, the state has outlined priority groups to receive program funds, creating a situation in which some eligible applicants will not receive benefits if program funds are exhausted by higher priority groups.

Priority Group 1 consists of referred clients, which includes TANF recipients, foster families, and homeless agencies; Priority Group 2 includes special or at-risk populations and special needs children; Priority Group 3 outlines eligibility based on “very low income” families that earn 50 percent of the state median income (SMI) or below, which is around $23,000 per year for a mother and her small child.

Finally, Priority Group 4 is made up of low-income families, defined as persons at or below 85 percent of state median income—$38,500 for a mother and her child. Priority Group 4 is where a waitlist can occur. It is “based on the availability of funding” and requires parents to be in a full-time educational program or working at least 25 hours per week.

Mississippi Reform Recommendations

A low-hanging fruit reform would be to end the unfair treatment (on paper) of two parents both living with their biological children. Currently, Mississippi defines a family unit, if the adults are unmarried, loosely. A family for the purposes of eligibility in the Child Care Payment Program is defined as, “Any person living in the household who is financially or legally responsible for the care of the child(ren) included in an application for a child care certificate.”

The definition first asks if an adult is legally responsible to care for a child (biologically related). If not, there is an economic unit test to judge whether an unmarried couple is sharing resources toward the care of the child. The latter test is of course much more subjective and easier to deceive than the first. Problematically, this excludes the live-in boyfriend, known to authorities, who is not a legal parent of the mother’s child, if the mother reports that the boyfriend doesn’t substantially contribute to the welfare of the child. Instead, Mississippi should count the incomes of all able-bodied adults in a home toward determining welfare eligibility—a “working age adults under one roof test”—not just the incomes of biological parents.

Addressing marriage penalties and benefit cliffs (where benefits suddenly fall off if a recipient gets married or makes too much money, leaving the recipient in a far worse overall financial situation) requires stronger action.

First, follow the federal tax code’s treatment of married couples, which factors in the earnings power two adults can have. Specifically, raise the eligibility threshold for working-class married couples to phase out the program between 1.4 and 1.7 times the eligibility threshold for the number of persons in the family minus one. For example, if two married parents have one infant child, their eligibility threshold should be 1.4 times the eligibility threshold that would exist if the family were made up of just the mother and her child. That enhanced eligibility should then phase out—via higher program copayments—between 1.4 times and 1.7 times the two-person family eligibility threshold.

To save taxpayer funds and allow families flexibility, this enhanced eligibility for married couples should require full-time work by the first spouse but allow part-time work by the second spouse, and only pay for part-time childcare commensurate with the part-time work.

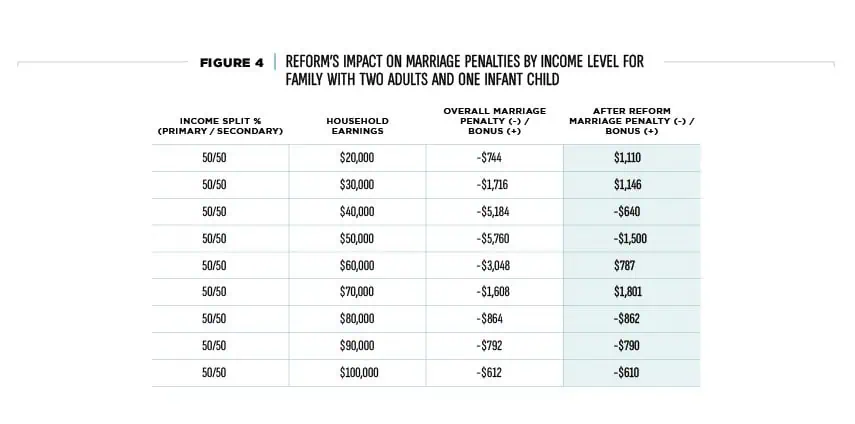

These reforms would reduce Mississippi’s marriage penalties by about 50 percent per year for couples who both earn relatively the same amount and have combined incomes between $40,000 and $80,000 per year.

Some caution is required. A reasonable concern is that these reforms involve pushing welfare into higher combined income brackets, but that’s only because welfare already reaches well into these combined income brackets. Another caveat is that a focus on greater childcare access alone is wrongheaded for two reasons.

First, subsidizing childcare generally leads to higher demand and more supply-side regulations, which in turn pushes costs higher. States like Minnesota, California, and Massachusetts subsidize their program much more than many other states, especially compared with southern U.S. states, and these states all have much lower childcare costs.

Second, most Americans say they would prefer to have one spouse stay at home with their children, and this is especially true of working-class parents. In other words, efforts to expand childcare subsidies generally at the state and federal level do not match the expressed opinions of many families. A better political approach is to keep the program size as-is, or even attempt to pair it back by going after fraud and abuse, while reducing marriage penalties in the program.

Conclusion

Overall, Americans widely support this type of social safety net reform. According to a recent survey, many respondents “talked about smoothing out the benefit cliffs that punish workers who are just outside of a given income threshold or [wanted a focus on] reducing marriage penalties….” In other words, a reform that addresses these issues without massively expanding the safety net is both popular with the general public, could receive bipartisan support, and would strengthen families, which ultimately provide the foundation for children to flourish.

Willis Krumholz is a research fellow at the Archbridge Institute. He is also a licensed attorney and a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) charterholder. Follow his work @WillKrumholz.