There are stories that take tragedy to unearth. When the world bears witness to great ability, new awareness changes the narrative of today and rewrites the influence of the past.

Walter Beech, stunt pilot and renowned engineer, built the Beech Aircraft Company into one highly regarded maker of small aircraft. The company helped win World War II, producing some 7,400 airplanes for the United States and Allied Forces. In this time, outsiders assumed Beech’s wife to be little more than a company secretary. That all changed on the night of November 29, 1950, when fifty-nine-year-old Walter died prematurely of a heart attack.

Under the leadership of Olive Ann Beech, the company’s 9,200 employees developed new airplanes, like the famous Beechcraft King Air, and played a role in the space industry. With a $6.5 million market value when she took the helm in 1950, Olive Ann ran Beech Aircraft for thirty years until she sold it to the electronics and defense giant Raytheon for $800 million ($2.4 billion in today’s dollars).

Against all odds in the male-dominated aviation and defense industries, Olive Ann quietly built a great American company and shaped the skies along the way. From humble beginnings, diligently pursuing success, and making her own breaks, this is her story.

Her Early Years

In a rural farmhouse in Waverly, Kansas (population eight hundred), Olive Ann Mellor was born on September 25, 1903. She was the youngest of four girls. Her parents, Susannah Miller Mellor and Franklin Benjamin Mellor, were strong working-class Americans from southeastern Ohio. Franklin was a building contractor, and Susannah raised pigs, geese, chickens, and a cow—selling the pigs and eggs for household money.

The family moved to Paola, Kansas, where the children attended elementary school. Olive Ann meticulously absorbed the world around her. “Sit on your own blisters,” and “Sit up straight and tall,” were maxims spoken often in the home. She wrote it down in her scrapbooks. Her mother, Susannah, was the dominant figure in the house: all family property was in her name, as were most decisions.

Susannah ensured Olive Ann learned finance early: at age seven she had her own bank account; by age eleven she was in charge of writing the checks to pay family bills. When Susannah had an idea to construct and operate hamburger stands, Franklin built all four stands and Susannah operated the business before selling it at a profit.

In 1917, when Olive Ann was fourteen, the family moved to the much larger city of Wichita. Instead of attending high school, Olive Ann signed up for business courses at the American Secretarial and Business College. In 1920, her training was complete. The seventeen-year-old went to live in Augusta, Kansas, finding work as a bookkeeper and office manager for the Staley Electrical Company. Combined with a side job keeping books for Joe’s Garage, she earned $18 a week.

Even outside of work, though, Olive Ann was determined to get ahead. One day she walked into a local bank and asked for a loan of $1,000. The banker was surprised. She had “things to buy” and talked him into it. Returning weeks later, she repaid the loan and earned a credit rating; just the thing she was looking to “buy.”

In 1925, Olive Ann returned to Wichita to accept a job as bookkeeper and secretary for a new aircraft company called Travel Air.

Seeds of Flight in Wichita

Wichita has become known as “The Air Capital of the World,” as it’s home to some of the largest aircraft manufacturers, including Textron Aviation, Learjet, and Spirit AeroSystems. All this grew from a few well-planted seeds in the early twentieth century.

In 1918, Kansas was producing 13 percent of US oil. This oil money flowed into Wichita, and local oil investors, flush with cash, invested in the airplane manufacturing industry.

In 1919, oil investor Jake Mollendick recruited famed pilot and designer E. M. Laird from Chicago to Wichita to help found the E. M. Laird Airplane Company. Laird had a knack for bringing together and developing talent. In 1920, Laird recruited a mechanic named Lloyd Stearman and a demonstration pilot named Walter Beech.

Walter Herschel Beech, born January 30, 1891, in Pulaski, Tennessee, was a self-taught pilot who built his first glider at the age of fourteen. He was a World War 1 flight instructor with the US Army Air Corps, excelling in mechanical work and trusted by fellow airmen.

Thousands came out to watch Walter race and perform air tricks; he sold Laird’s airplanes by winning these flying contests and succeeded as one of the best daredevil flyers of the day. In the air, his work gave him new ideas for aircraft construction. On the ground Beech worked with Stearman to work the new designs into aircraft at Laird’s.

Forty miles away a brilliant airplane designer named Clyde Cessna was making more money from farming than from his airplane designs. In Wichita, Cessna was a growing celebrity: in 1917, he was the first to build an airplane in Wichita, and in the same year he set both a national airspeed record of 124 mph and a distance record, flying his own airplane seventy-six miles to Wichita.

In 1923, Laird’s was renamed the Swallow Airplane Manufacturing Company when Laird left after a falling out with Mollendick. A year later, Beech and Stearman also left to pursue their own design. Realizing many aircraft injuries came from splintering wooden aircraft they saw an opportunity in using metal for aircraft frames.

Travel Air – The Precursor

Approaching Clyde Cessna, Beech and Stearman convinced him to help start a new manufacturing company. Along with merchant Walter Innes, Jr., the three founded Travel Air Manufacturing Company in 1925.

One of Travel Air’s first hires was a new bookkeeper and secretary—twenty-one-year-old Olive Ann Mellor. With eleven of the twelve men married, Walter Beech made Mellor first promise to keep her hands off them; with that promise, she was given the job.

Two months in, Travel Air’s first plane was ready to fly: the biplane Model A, engineered by Lloyd Stearman. The biplane, a fixed-wing aircraft with two wings stacked on top of each other, is a design that goes back to the first successful airplane—the Wright brothers’ 1903 famed Wright Flyer. The Wright Flyer, a biplane made of spruce, reached a top speed of 30 mph. Twenty-two years later, Travel Air’s Model A biplane, a metal-framed design with elements borrowed from the best World War 1 fighter aircraft, cruised at 85 mph, and could reach a maximum speed of 96 mph. Most subsequent Travel Air biplanes derived their design from the Model A. In Travel Air’s first year, they made nineteen aircraft, and forty-six the following year. By the end of the 1920s, they had manufactured 1,700 airplanes, making Travel Air a major player in the industry.

Cessna as president was a brilliant airplane designer, but a mediocre salesman. He was so enthusiastic in telling prospective buyers about the company’s upcoming designs he would lose the sale on the current design. Customers decided to wait for the next one. Sales were Beech’s domain. Beech, ever the effective racer, turned victories into sales, appealing to those with a taste for speed, status, and comfort.

Olive Ann hired other girls to do the routine work and became office manager. This freed her to focus on company finances and referee arguments between Beech, Stearman, and Cessna. Before long, Stearman left Travel Air to build airplanes in California for the movie industry. The following year, 1927, Cessna sold his initial stake and left Travel Air to follow his dream of building monoplanes of his own design and name. The company he built became Cessna Aircraft.

Travel Air, without Cessna and Stearman, succeeded despite the occasional hitch. When cash ran short, Walter would take people up for rides at fairs and air shows, with Olive Ann selling the tickets.

By late 1928, like the financial markets, aircraft demand was soaring. Yet, strong demand didn’t guarantee survival. When other airplane companies collapsed from internal troubles, Olive Ann kept Travel Air solvent. The next year she urged Walter to sell the company to Curtiss-Wright—the makers of Travel Air’s engines and descendent of the original Wright Brothers’ company. The timing was right.

In August 1929, Walter and Travel Air shareholders accepted the merger offer by Curtiss-Wright for $3.5 million. Travel Air shareholders received 1 3/4 shares of Curtiss-Wright for every share they held. Walter’s share netted him $1 million in stock in Curtiss-Wright, worth $14 million today.

Walter and Olive Ann

Walter was thirty-nine, and Olive Ann was twenty-six. She called him Popper and he called her Annie. She enjoyed working in the office, and he enjoyed working in a plane. The two were opposites, and they were in love—and at times unpredictable together.

Once at a formal reception for their engagement, standing by the pool to have their picture taken, Walter pulled Olive Ann into the pool. She was terribly upset and told Walter her clothes and jewelry were ruined, thanked the hosts for the lovely party, the guests for coming, got in the chauffeured car and went home. She didn’t talk to him for days. She went out and bought new sets of jewelry and clothing then sent the hefty bill to Walter. In the end, Walter paid.

Walter Beech and Olive Ann Mellor wed on February 24, 1930, in the beautiful mansion of a friend of Walter’s. After the wedding, the couple moved to New York.

Walter was a vice president at Curtiss-Wright and president of Travel Air, one of twelve divisions within Curtiss-Wright, then the country’s largest aircraft firm. He quickly tired of the desk life, however. Olive Ann, while enjoying Broadway shows and fine restaurants, soon realized work was her lifeblood. As the Great Depression deepened in 1931, Curtiss-Wright stopped producing Travel Air planes and closed the Wichita plant.

The couple shared the ups and downs of marriage—albeit in their own way. Walter once angered Olive Ann so much that she walked down to Grand Central Station and bought a train ticket back to Wichita. In the Midwest, the train stopped. Passengers were told, “Some fool has his airplane on the tracks.” The fool was Walter. Walking to Olive Ann’s railway car he apologized and flew her away in his airplane.

Founding Beechcraft

Late in 1931, Walter resigned from Curtiss-Wright and left New York with Olive Ann to return to Wichita. With her and the backing of some Travel Air investors, Walter launched the Beech Aircraft Company.

Their first design was the Model 17, later named the Staggerwing. In extra warehouse space offered by Clyde Cessna, the company set up shop. By 1935, they were back in the original Travel Air facilities in Wichita and employing most of the same people. Beech Aircraft was Travel Air reincarnated.

The name Staggerwing comes from the fact that the upper wing sat further back than the lower wing. With a cabin, passengers could sit enclosed and in comfort. The Staggerwing was quick and powerful with a design that maximized pilot visibility and made flights smoother.

“I made him pay me a salary or I wouldn’t work. … I wasn’t willing to give my life’s blood and not have it properly evaluated.”

Though Olive Ann had the financial experience necessary to run the company, her role was viewed as that of just a “helper.” One example can be seen in Walter’s recounting of the company’s start, “In April 1932, I returned to Wichita and with my own capital, a few employees (an engineer, designer, and helper), [and] started the Beech Aircraft Company.” Olive Ann wasn’t even mentioned by name. Corporate biographies written after 1950, however, were more cognizant of Olive Ann’s early contributions.

“I made him pay me a salary or I wouldn’t work.” she later said, “I wasn’t willing to give my life’s blood and not have it properly evaluated.” She continued demanding her rights. When the company went public as Beech Aircraft Corp in 1936 she held 552 shares of the company and was the third largest shareholder behind Walter’s 10,080 shares and Harris Thompson’s 3,750.

Like Travel Air, Beech Aircraft’s planes, now branded Beechcraft, became the limousines of the skies. The planes could reach speeds of 200 miles per hour with a non-stop range of one thousand miles and had an interior that was as luxurious as the plane was powerful.

It was Olive Ann who balanced the books for the company, ensuring payroll and bills were met. She enjoyed working. One night she called Louise Thaden, the aviatrix who had previously set records flying planes for Travel Air. The Bendix Transcontinental Trophy Race—from New York to Los Angeles—had posted an additional $2,500 award for the first female pilot to finish. Olive Ann thought Louise should go for the extra money. In the 1920s and ’30s air races were extremely popular, and The Bendix was one of America’s most famous cross-country races.

Thaden was no ordinary aviatrix. Twenty-four hours, fifty-five minutes, and one second after taking off from New York, Louise Thaden and Blanche Noyes landed their Staggerwing in Los Angeles, where Olive Ann was standing, tear in her eye.

Thaden and Noyes had beaten all other female contestants, as well as all the men. They were not just great pilots among female pilots; they were great pilots, period. Forty-five minutes later, the second place finishers crossed the finish line.

In January 1937, Beech Aircraft launched the Model 18, known as the Twin Beech. Seating six to eight passengers, the twin-engine all-metal monoplane craft was wildly successful. The plane was used as an executive aircraft and as an airliner for routes that fed passengers into main cross-country airline routes. In Canada, Model 18s were mounted with skis for service in the snow; to land in lakes they were mounted with floats. That same year the first Beech daughter, Suzanne, was born.

Walter was the engineering and production genius; Olive Ann was devoted to the finances and management of their enterprise. But by 1938, the company was struggling, as was nearly every other company during the Depression era. They nearly broke even with revenues of $1.1 million and a loss of $1,600. The next year, however, losses extended to $91,479 and revenues only increased slightly—to $1.3 million. Though the company laid off workers in 1939, with war on the horizon the company’s future was not bleak.

The War Years

June, 1940. Walter Herschel Beech, the chairman and president of Beech Aircraft, was in the hospital. He was in a coma with encephalitis. The thirty-six-year-old Olive Ann was on the same floor to deliver their second child.

It was there that news reached Olive Ann: some of the company’s executives were internally spreading the story that Walter wasn’t coming back—that they were the better to lead. With Beech’s co-founders stuck in a Wichita hospital, the executives had calculated the right time to remove the man in charge; only they had forgotten half of the equation.

As secretary-treasurer, Olive Ann worked ten to twelve hours a day. Her temporary change in location did little to slow her. She ordered a direct hospital-to-plant telephone line set up and her directors to meet by her bedside. Ignoring men who thought the business of the aircraft industry was no place for a woman, Olive Ann took charge of Beech Aircraft.

Something proved successful. Fourteen men were dismissed, and Olive Ann would guide the company until her husband returned to the leadership role. It was from this moment on that Olive Beech was officially leading from behind the scenes.

“The majority of people today don’t know what the joy of work is.”

Halfway through 1940, commercial production was suspended and the company converted the Model 17 and 18 to military use. Employment rose from 750 in 1939 to 2,100 in 1940; 4,000 in 1942; and a wartime peak of 17,200.

Beech Aircraft was fortunate to have Olive Ann. After giving birth to her second daughter, Mary Lynn, Olive Ann and two associates went to Washington and secured a $13 million Reconstruction Finance Corporation revolving credit. During the war she negotiated a revolving $50 million credit with thirty-six banks. “You have to be honest to pry that kind of money out of lenders,” she later said.

Company production was not limited to Beech facilities. With Olive Ann at the helm, over ten thousand employees were working on Beech production at subcontractor facilities. Due to the wartime metal shortage, the company and subcontractors produced a plywood trainer known as the AT-10. Over 90 percent of US navigators and bombardiers in World War II trained in Beech aircraft.

Olive Ann learned to surround herself with loyal executives. John Gaty was one such loyal individual. Having worked closely with Walter, Gaty was a competent executive and often a go-between with those who didn’t work well with Olive Ann. The fact that she ran the company, not Walter, was not to be publicized; feigning normalcy wasn’t easy—when wartime government inspectors would visit, the story went that Walter was out of town.

If the rapid change in employee headcount from 750 to 17,200 was astonishing, revenues were too: climbing from a pre-war $1.3 million in 1939 to $123 million in 1945.

When Walter returned to leadership, he found Olive Ann wasn’t quite ready to abandon the driver seat. That was all right with him. He would regularly leave the office for fishing trips and safari hunts. At directors’ meetings, he’d step out for haircuts saying, “Annie can handle this.”

Looking toward the future, Olive Ann foresaw trouble with the end of the war when the company would transition back to commercial production. Planning ahead, the company began designing a new airplane, the Beech Bonanza, a plane that would go on to have the longest continuous production of its kind—over seventeen thousand built from 1947 to present day.

After the war, Beech Aircraft turned to diversified manufacturing to bring in enough money to keep paying their experienced employees. They produced a wild array of products—from corn harvesters to cotton pickers to washing machines. It wasn’t enough. In 1946, revenues crashed from $123 million down to $24 million. The company saw a loss of $228,000 in 1946 and a loss of $1.8 million in 1947.

Then Walter died unexpectedly of a heart attack on the night of November 29, 1950, at age fifty-nine. Olive Ann was forty-seven. She was an intensely private person, so it remains largely unknown how she reacted to the loss of her husband.

Tributes and sympathies poured in from across the country. One day at a time was Olive Ann’s remedy. In a bittersweet moment, her day had come to officially take the driver’s seat. The board of directors chose Olive Ann Beech to lead the company as president and chairman of the board of Beech Aircraft.

The ’50s–Officially Leading the Company

“Though the décor of our individual offices may vary, the daily problems on our desks are no different. The kind of woman who can function in an executive job is one who can handle that job, and it’s just about that simple.”

Olive Ann signed her name “O. A. Beech,” purposely erasing any sign of gender. She believed her self-worth had everything to do with her skill, track record, and experience. As president and CEO, she selected executives based on trust: Gaty, and Frank Hendrick. Hendrick was her nephew, who had been with the company ten years.

Nevertheless, attempts to unseat her came quickly following the death of her husband. Within the ranks there were those who believed a woman couldn’t run the company. Among others, Olive Ann forced the resignation of a Beech family member—Walter’s brother.

She developed her own management techniques that were useful as a woman at the helm of a major aircraft manufacturer. She seldom held large group management meetings; when she did, she kept them short. Her technique allowed her to minimize vulnerability while maximizing authority. She ensured herself the upper hand and the home field advantage. In the morning she would scan the large stacks of mail that came in, scribbling a note on some letters: “See me.” Stories were told of grown men flinching when they were summoned by her secretary to stand on her blue carpet.

Her office was a large square room on the first floor of the manufacturing plant. Outside her door, she hung a flag—a sunny one that showed she was in a good mood, and one of storm clouds when things weren’t going well.

One annoyance that constantly ran up the storm cloud flag was taxes. By 1955, $4 million out of the company’s $7 million in profits went to taxes. There were sunny flag tax days too, however. During the war years, Beech Aircraft had to pay an Excess Profits Tax: earnings deemed in excess of normal income. In 1953, after a ruling on another company’s tax claim, Beech was able to make a claim and ultimately be paid $4.2 million in refunded income.

Though the company revenues fluctuated with the Korean War, climbing to the decade’s peak of $140 million in 1953, the general trend was upward. The company began the decade with $16 million in sales and closed the decade with $89 million in sales and $3.9 million in income.

As CEO, Olive Ann’s interaction with the press was limited. Like the famous oil tycoon, John D. Rockefeller, Sr., she had a habit of shunning the press. Though she’d reap praise from magazines like the Christian Science Monitor, calling her “The First Lady of Aviation,” she saw little value in her press interaction.

Finally, in 1959, her press relations manager convinced her to sit down with the Saturday Evening Post for an in-depth profile. The reporter came to Wichita and spent a few weeks on site. The result was the August 1959 article titled Danger: Boss Lady at Work.

“Mrs. B—and only members of her innermost council call her that—is hardly the female version of an organization man who made good.” The article tore into Olive Ann, her personality and her leadership. It’d be the last time she’d allow a reporter so deeply into her life.

The ’60s

Olive cared for her company and its employees though. When someone had spent twenty-five or more years with the company, she took joy in personally placing a pin on them. The employees also looked forward to the occasion. At other times she invited small groups of workers to lunch. It helped her keep a pulse on the company, boosted the morale of factory workers, and improved the flow of ideas.

“Talent is where you find it, it is no respecter of men or women, young or old.”

In 1965, crosstown Wichita rival Bill Lear’s Learjet was taking off—the Learjet was one of the first affordable private jets. Some of the people at Beech Aircraft worried that they’d be left behind. In 1966, facing a shortage of capital, Lear offered to sell the company to Beech at an attractive price. Olive Ann struck down the idea, saying she “wasn’t going to pull Bill Lear’s chestnuts out of the fire.”

Though she tested the technology, Olive Ann never dove headfirst into jets. “Slowly We Go” was her policy. She chose instead to invest in the already profitable and successful line of turboprops; “Beech is not living with the times” was the generalized muttering heard around the town. Yet, her policy worked well for Beech Aircraft, her employees, and investors. In 1966, the year she declined to buy Learjet, Beech Aircraft had 9,988 employees generating $164.5 million in revenue and $8.7 million in profits.

Olive Ann’s strategy to build upon success is similar to one used by Katherine Graham, CEO of the Washington Post Company in the 1980s. When other large newspaper companies spent hundreds of millions of dollars to build new printing facilities for color printing, Graham was one of the few who held off. It worked. Graham deferred the costly investment until costs had dropped and the benefits were proven.

For Beech Aircraft one turboprop worth building was the King Air. The twin-turboprop executive aircraft found success with military and government users, corporate users, and commercial air taxi companies.

One famous customer was President Lyndon B. Johnson, whose King Air became the Air Force One every time he used it to fly from Austin, Texas, to his ranch fifty miles west. President Johnson spent almost 20 percent of his time at the ranch known as the “Texas White House.”

Beech Aircraft had a long line of celebrity customers who beat a path to Wichita for their custom planes. Uncomfortable giving speeches to large groups, Olive Ann was relaxed hosting these many famous people. Bob Hope, Walt Disney, and the Aga Khan were a few of many.

Taking a Step Back

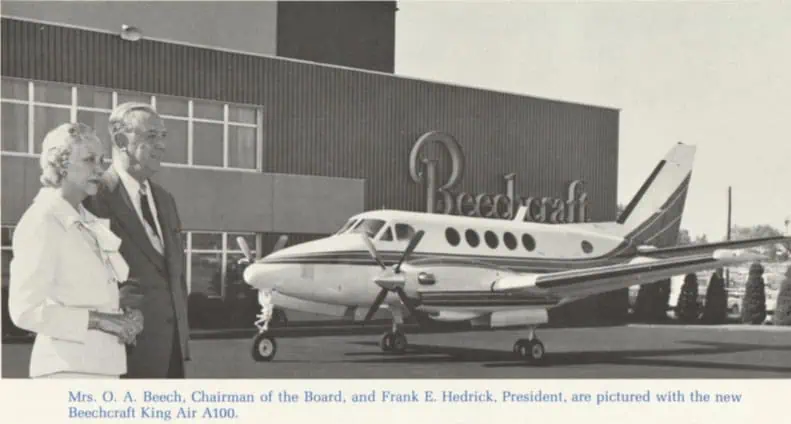

In 1968, after eighteen years as president and CEO, Olive Ann gave more power to her nephew, Frank Hendrick, announcing his role as president. She kept the role of chairman of the board and chief executive officer. At sixty-five, she began stepping back in her hourly duties, though she still remained the ultimate authority and had the last word.

As president, Frank Hendrick was a well-respected executive in the industry. His presence gave the company extra energy as it saw its first employee strike—a twenty-six-day strike in 1969—and a product liability crisis, the latter of which Hendrick and Olive Ann solved. No longer producing farm equipment, Beech Aircraft began branching outside of traditional aircraft production, supplying products for NASA’s Gemini program, the Apollo program, and the space shuttle programs.

In April 1970, the company eased its way into jets. Announcing a new subsidiary, the Beechcraft Hawker Corporation, Beech Aircraft acquired the assets and personnel of Hawker Siddeley International. The two companies would jointly develop, produce, and market business jet aircraft. After five years the joint marketing agreement came to a close.

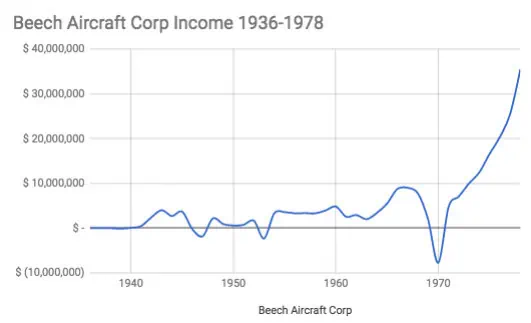

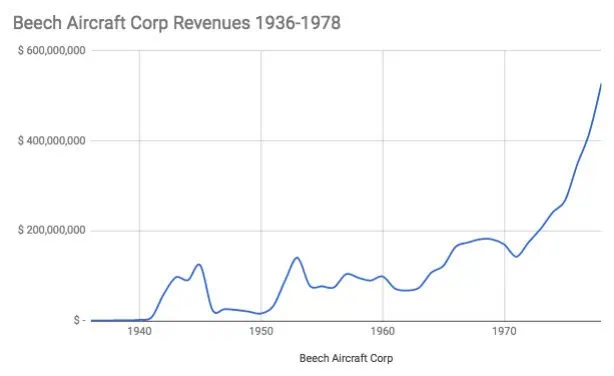

Charts of Beech Aircraft Revenues and Net Income. Source: Corporate annual reports.

Company revenues continued to grow, climbing from $98 million in 1960 to $169 million in 1970 and $267 million in 1975; profits followed in a steady growth. In 1973, at the age of seventy, having been with the company forty-one years, Olive Ann tasked Hendrick with finding a new home for Beech Aircraft.

On February 8, 1980, the Raytheon Company purchased Beech Aircraft for $800 million. Olive Ann was seventy-seven. She stayed on the board of directors of Raytheon for two more years, bringing her involvement with Beech Aircraft to a total of fifty years. After those two years, however, the new owners made changes, and both Hendrick and Beech were ousted. Olive Ann told an upset Hendrick: “Mr. Hendrick, we sold the farm. If they don’t like us living on it, that is their prerogative.”

If one invested in Beech Aircraft when Olive Ann first became CEO in late 1950, cashing out when Olive sold the company in 1980, they’d have an average annual return of 18 percent over twenty-nine years. $10,000 invested returned $1.23 million—excluding dividends, which Beech Aircraft gave generously. For comparison, $10,000 invested in the S&P 500 over the same period would return $159,400.

Enjoying Her Eighties

Continuing a habit she had started in 1954, Olive Ann made regular visits to a log cabin outside of rocky Mountain National Park, spending time with her daughters and grandchildren. Her driver would take her there in her famous Cadillac—painted beech blue.

As the first lady of aviation, Olive Ann was racking up a pile of awards to go with the title. In 1963, she was appointed by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services. Four years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson named her to serve on the President’s Commission on White House Fellows. Olive Ann Beech was listed by Fortune as one of the ten highest-ranking women in business in the 1970s; she received the prestigious Wright brothers’ trophy in 1980; in 1982, she received an honorary doctorate from Wichita State University. In 1981, Olive Ann joined Walter in the Aviation Hall of Fame.

“And therein lies the secret. As long as there exists a shortage of thinkers, as long as there remains a demand for do-ers, women executives will be at work helping build a better nation in a better world.”

From The Woman Executive by Olive Ann Beech

When the company sold, Olive Ann’s near 7 percent was worth over $50 million in 1980—an amount worth $110 million today. In the mid-60s, she had given what would be another 7 percent to her daughters. With her money, Olive Ann quietly donated to local charities—everything from area college scholarships to the Salvation Army, her church (the First United Methodist Church of Wichita), the Soroptimist International of Wichita, and the local art museum. With the Cessna family, she pledged $2 million to a museum, on the condition that the museum supporters round up the first $8 million first.

On July 6, 1993, Olive Ann Beech died of heart failure in her home in Wichita, Kansas, at the age of eighty-nine.

At her funeral, her pastor and friend spoke in memory: “In her mind there were responsibilities in being a good citizen. Some things you just did.” Wichita was proud of Olive Ann and she’d been proud of Wichita. In addition to the millions of dollars she left behind to benefit the city, her lasting contribution to the world was the great company she built, the livelihood for thousands, and the 53,697 airplanes that Beech Aircraft produced.

It wasn’t until she assumed the role of CEO that the world could fully witness her great ability. Though she herself never learned to fly, in a time of great historical turbulence, she was the steady hand that took Beech Aircraft to new heights. And like the great aviatrixes of the day, Olive Ann Mellor Beech was more than just a great executive among female executives. She was simply a great executive.

…

In 2006, Raytheon sold Beech Aircraft to a newly formed company named Hawker Beechcraft, which subsequently went bankrupt, and in 2013 Textron agreed to purchase Beechcraft. Textron planned that Beechcraft and another company it owned, Cessna Aircraft, would be combined.

Sources

The preceding story is based on the comprehensive biography of Olive Ann Beech, The Barnstormer and the Lady: Aviation Legends Walter and Olive Ann Beech by Dennis Farney. Additional sources were The history of Beech (Beechcraft: Fifty Years of Excellence, 1932–1982); Boss Lady: How Three Women Entrepreneurs Built Successful Big Businesses in the Mid-Twentieth Century by Edith Sparks; the 1942 Time magazine article on Olive and Walter; “The Woman Executive” essay by Olive Ann Beech in a 1961 Michigan Business Review article; “Danger: Boss Lady at Work” by Peter Wyden, published August 8, 1959 in the Saturday Evening Post; Moody’s Analyses of Investments, years 1936–1981; The Outsiders by William N. Thorndike, Jr.; and the Annual Reports from the Beech Aircraft Corporation, years 1936 to 1979.