Born in rural Pennsylvania in 1857, Milton Hershey attended seven different schools and never made it beyond the fourth grade. At fifteen, he found his passion in a Lancaster ice cream parlor making candies. His father, Henry, was a dreamer, chasing oil gushers and silver rushes, and his mother, Fanny, a strict Mennonite. Both supported and encouraged Milton to be his greatest self.

After a decade and three failed candy companies, twenty-nine-year-old Hershey finally succeeded, creating one of America’s most successful caramel companies. At forty-two, the king of caramel surprised the industry when he sold his Lancaster Caramel Company to a rival for $1 million ($31 million in 2019 dollars). If he had retired and spent his remaining years traveling the world with his wife, Catherine, one might never have known the name Hershey.

But Hershey could not stop inventing new candies and couldn’t shake his obsession with finding a way to mass-produce milk chocolate, a new phenomenon that only had been cracked in 1875 by the Swiss. In 1900 he went all-in on milk chocolate, building a massive factory and utopian chocolate town on empty Pennsylvania farmland. In the ensuing years, he changed the American palate, and in his wake, he left his name on a company, a city, and an orphanage. This is his story.

Early Years on the Homestead

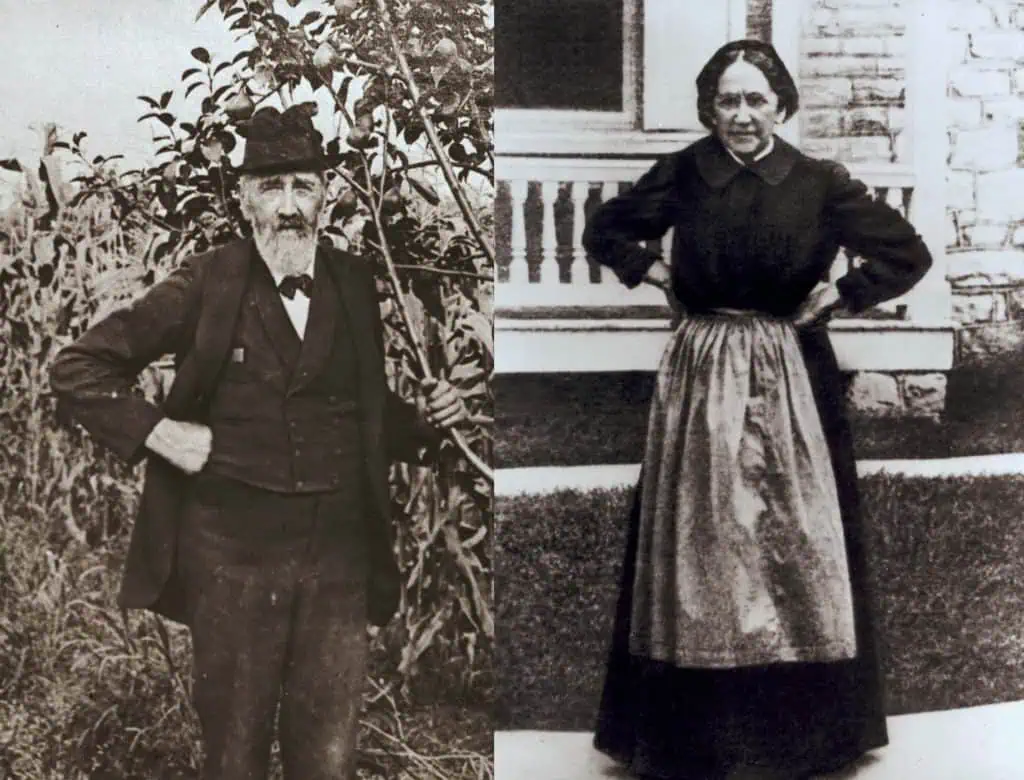

It was September 13, 1857, when on a homestead twenty miles north of Lancaster in the Lebanon Valley of Pennsylvania, Milton Snavely Hershey was born to Henry and Veronica “Fanny” Snavely Hershey.

Henry Hershey was a dreamer, had always wanted to be a writer, a painter, and a person of wealth. But he was the kind of man who was late to his own wedding, arriving only to outshine his bride with striped pants, a silk vest, and fancy hat. Though he chased silver rushes and get-rich-quick schemes, he always wanted his son, Milton, to get an education, to fulfill his own failed dreams.

Fanny, Milton’s mother, did not share Henry’s enthusiasm for Milton’s education. The daughter of a bishop, she was born to wealth; the Snavely family having grown up with the “Do the hard work” mentality of the Pennsylvania Dutch (also called Pennsylvania Deutsch, who were actually of German descent, not Dutch).

Poor and unable to make a success of the farm, Henry sold it to pay off his debts and took his family and the money to the hellhole known as Oil City, Pennsylvania. As Fanny and young Milton sheltered in a rented room, Henry went off in search of prospectors to invest his remaining cash in.

When Fanny’s brothers learned that she was pregnant with her second child and their aloof degenerate of a brother-in-law was quickly running out of money, they made their way to the Oil Creek Valley and paid to bring Henry, Fanny, and Milton back to Lancaster. Fanny’s brothers set Henry up with a shoddy piece of farmland they owned, many miles from the rest of the family. Sarena, the second child, was born in 1862.

On the farm, Fanny raised the chickens, churned the butter, and sold the eggs. Henry planted fruit trees and experimented with dams to stock fish. In Milton, Henry instilled the joy of never-ending experiments. Yet Fanny resented Henry for dragging the family into his get-rich-quick schemes. Money problems only fueled their arguments. In the winter of 1867, at the age of four, Sarena caught scarlet fever and passed away. A tragedy for young Milton, Sarena’s death was the final straw for Fanny and Henry. Owing to her religious background, they never divorced and continued to live together, but the relationship was over. From then on, Fanny devoted her life to her church and her son. For Milton, she imagined a prosperous life as a farmer or a Lancaster businessman.

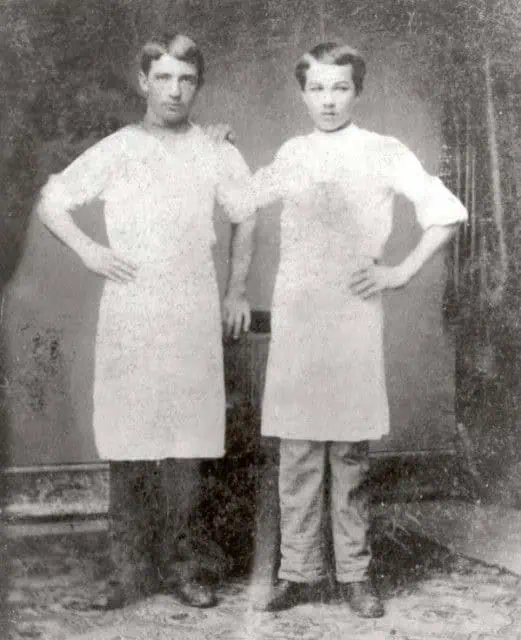

After seven different schools, Milton’s formal schooling ended at age twelve. Two years later, Henry got Milton a job as a printer’s apprentice. After a few months, not liking his boss or the work, Milton dropped his wide-brimmed hat into the printing press, creating a giant ink pie on the paper, and was quickly fired. Fanny, who saw the job as Henry’s idea and a poor fit for Milton’s future, was glad to hear the news.

Fanny’s sister, Milton’s Aunt Mattie, got him a job working at Royer’s Ice Cream Parlor and Garden in Lancaster. As a young boy, Royer’s was the place to see pretty girls and important people in town. First assigned to handle the horses of the shop’s customers, Milton made an impression on his boss. Fanny pushed Joseph Royer to set her son making candy as she saw more opportunity for Milton in candy rather than ice cream.

Candies in 1872 were made of boiled sugar: lollipops, lemon drops, rock candies. At the time, chocolate remained bitter and was used for coating. (Historians have found that as far back as the Mayan civilization, and likely farther, people drank the bitter liquid of chocolate mixed with spices.) Nobody had yet figured out how to make chocolate bars with milk and sugar. And it would not be until 1875 that Switzerland’s Daniel Peter would create the world’s first solid milk chocolate using his neighbor Henri Nestlé’s invention of condensed milk.

Apprenticing under Joseph Royer, Milton learned the value of making the customer happy. In the kitchen, he was a natural at the timing of taffy pulling, a job that required strength as one needed to take a hot semi-solid sugar from kettles and pull it into a candy.

Milton’s First Shop

In a time before television and radio, the automobile or the light bulb, citizens of the world would travel to World’s Fairs to see the newest inventions of the day.

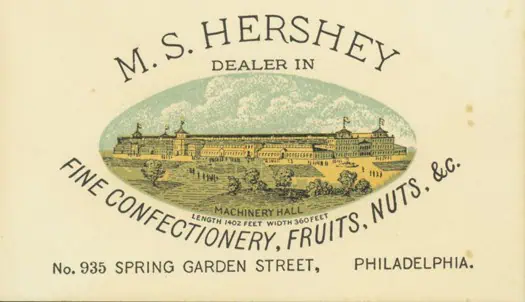

The Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 was the first official World’s Fair to be held in the United States. With news of thirty-seven countries participating and an expected attendance in the millions, Milton Hershey and the Snavely family got the idea that the young candy-maker should open up a candy shop in Philadelphia, seventy miles away from Lancaster.

With money from the Snavely uncles and Aunt Mattie, Hershey opened up his first candy shop on June 1 on Philadelphia’s Spring Garden Street. There were many other such candy shops popping up, and little of what he did there was out of the ordinary, though some things were creative: Milton installed an air chute to carry the candy scent from his basement kitchen to the outside air. Fairgoers could catch a scent and be drawn in.

Milton spent his nights in the basement making candies and his days selling them, with the help of Fanny, Aunt Mattie, and some hired hands. They saw a steady stream of customers as the fairgoers stopped at Hershey’s shop to buy candy.

Visiting the Centennial Exhibition required several days to see so many new things for the first time: new food products like popcorn, ketchup, and root beer; the cables for the Brooklyn Bridge; the arm and torch of the Statue of Liberty; technologies like Thomas Edison’s telegraph and Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone. Remington, already famous for its rifles and sewing machines, unveiled a newly commercialized “Sholes and Glidden typewriter,” a machine that would popularize the QWERTY layout and shift keys we use today. This marked an era when mass production was becoming possible. Fairgoers could see mass-produced stoves, guns, sewing machines, and carriages.

By November of 1876, the exhibition was over. Everything began to fold up and the temporary exhibits were destroyed or carted off.

Sensing an opportunity for his shop, or perhaps with nowhere else to go, Milton stuck around to sell his candy at wholesale to the myriad other shops in the growing city. At that time Philadelphia had a population of approximately 820,000, second only to New York City’s 1.2 million.

Problems in Philadelphia

With little formal education, Milton struggled to balance the books. He hired a young businessman from Lancaster, William “Lebbie” Lebkicher, to do his bookkeeping. Lebkicher, twelve years older, was a Civil War veteran with a lifetime’s more experience. He was quick to see that Milton was running into cash problems. Wholesale customers paid slowly, and suppliers had tight credit terms.Lebkicher helped Milton tighten his focus onto his customer-favored caramels, eliminating the unprofitable and short-shelf-life items. Milton, who was an extremely hard worker, fidgety, and full of energy, found that Lebbie was the only man he could not outwork.

Still bleeding money, and with Aunt Mattie’s blessing, Milton wrote his uncles for money. Even as he cut costs, moving to a cheaper building, things continued heading south. Then his father, Henry Hershey, showed up.

Against the objections of Fanny and Aunt Mattie, Milton welcomed Henry, and for a time attempted to sell his cough drops and candy cabinets, built to display the goodies inside. Neither sold well.

For five years, Milton continued to work tirelessly, making candies at night and selling them by day. But the pressure was too much and he became ill. With Milton unable to leave his bed, Aunt Mattie and bookkeeper Lebbie kept the place going. All through 1881, he borrowed from his family. Then one day the word came down from his uncles in Lancaster that no more money would be coming for him.

His uncles, who owned and invested in a tannery, land, and a cotton mill, advised him to close up his shop. They suggested he sell or salvage what he could, pack it all in, and try again another day in another location.

Twenty-four-year-old Milton Hershey had spent his last six years focused on making his business work. He was burnt out. To top it off, his uncles and family had lost faith in him.

His cousins brought in a big wagon, helped him load up his kettles, and they all rode back to Lancaster together.

Onward to Colorado …Westward Bound and Back

Henry Hershey had gone to Denver, following word of a silver rush near Leadville, Colorado, and wrote Milton to come join him. Still ill and feeling like a failure, Milton agreed with a doctor who said the Colorado air would be good for his lungs.

There he saw the place for what it was, a pipe dream: all the easily mined silver was long gone. Ignoring prospecting, and his father, he found work in a Denver candy shop. The store specialized in caramels. Instead of using paraffin, as was common at the time to give the candy some chew, this candy maker used fresh milk, vanilla, and sugar. What followed was a soft, smooth, and sweet caramel with a longer shelf life. Milton practiced and memorized the process. Not long after, in the summer of 1882, Milton and Henry left Colorado for Chicago.

In Chicago, the two, full of energy, started a business making candy to sell to retailers in a basement on State Street, the heart of Chicago’s shopping district. The business fell apart when Henry endorsed a friend’s bad loan.

Henry stayed in Chicago, working as a business agent, living in a flophouse, but listing his address as the prestigious Palmer Hotel. Milton went eastward to Lancaster to see if he could get the Snavelys to invest in his idea for a shop in New York City.

New York City

This time, the Snavelys had no money for Milton.

The year was 1883. After his experiences in Philadelphia, Colorado, and Chicago, twenty-six-year-old Milton intended to start small. He found work at a local New York City shop—Huyler’s Candies—and got the lay of the land, creating his own candies at night. Huyler had two shops: one in the bustling financial district, the other on Broadway near Union Square, on the “Ladies’ Mile,” Manhattan’s most important shopping district. It was from Huyler’s successful shops that Milton learned the value of a great location.

By the spring of 1884, Milton was working seven days a week at his own shop in Midtown Manhattan on 6th Avenue between 42nd and 43rd streets. Customers bought candies and strolled to the nearby park, where they walked atop a 25-foot-wide, 50-foot-tall wall of the Croton Reservoir. That park today is called Bryant Park.

That summer, sales were strong and twenty-seven-year-old Hershey was able to hire some of the neighborhood girls to work in his shop. Fanny and Aunt Mattie came up to help, as did Lebkicher. Things were looking good. He was also making more wholesale deliveries to pushcart vendors and small shops in the area. Then Henry Hershey found his way to New York City.

Milton was convinced of Henry’s idea that New York City’s winter population would be ripe for Henry’s cough drops. He ordered the machinery and got to work.

At the time, New Yorkers loved Smith Brothers Cough Drops, one of the first trademarked products in America. The Smith Brothers would deliver large milk pails filled with cough drops to apartments where families could box them up. This gave Smith Brothers a lower cost of production and ensured they could easily beat other competitors who manufactured and packaged from their costly retail locations.

For another year Milton Hershey continued selling candies and cough drops, sales were only lukewarm. Milton slowly learned the hard way how difficult it was to take on an established brand. But, believing he only needed more room and more staff, he moved the business to a larger space on 42nd street.

Then in the summer of 1886, the proverbial walls caved in. The supplier of the cough drop making equipment demanded his $10,000, which Hershey did not have. At the same time, his previous landlord sued to keep Milton paying his old lease. Not wanting to borrow from family, he closed up shop and sent his equipment and supplies by train back to Lancaster. He followed the shipment with so little in his pockets that he had to ask Lebkicher to pay the railroad to release his crates.

Lancaster Caramel Company

It was 1886. Now back in Lancaster, a much older-looking, bushy-mustached twenty-eight-year-old Milton Hershey went to his uncles to ask for just one more loan. Then to Aunt Mattie. He figured he had a hometown advantage and experience enough. They all turned him down. They saw him as his father, a black sheep, something that Hershey would later remark was a motivating and emotionally liberating realization.

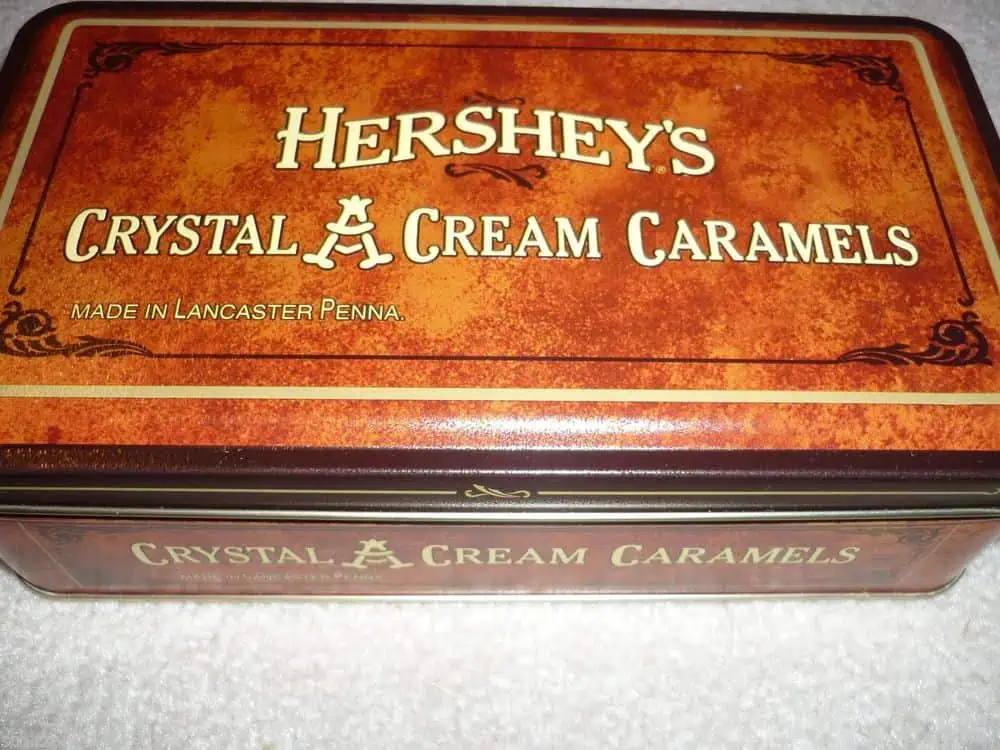

With supplies left over from New York, Milton made candy and sold it with a handbasket on the streets of Lancaster. Using fresh milk and what he had learned in Denver, he was able to create a caramel that had a taste customers loved. With more sales he bought a pushcart and rented a small space for production.

Though Aunt Mattie had turned him down for a loan, after his small success she lent Milton her good name and allowed him to use a row house she owned as collateral. He was able to get a ninety-day loan of $700 to buy equipment.

Just before the loan was due, an English importer found Hershey’s caramels and was amazed by the unique taste. When he learned of their months-long shelf life he placed a large order promising to pay if the candy arrived in London in good condition.

Milton Hershey, confident in himself, walked down to the bank and explained his situation to a junior officer: he did not have the $700 and he needed an additional $1,000 to fill this new order. The officer, after visiting Milton’s tiny wagon-maker’s shed used for production, and appreciating that Milton did not embellish his situation, personally signed for the note.

Just days before the note was due, a check arrived for five hundred British pounds (about $65,000 today). From there, sales of Hershey’s “Crystal A,” the brand name Milton gave his caramels, steadily took off. A large portion of the sales came from Europe. He continued hiring and growing, and by 1894 the Lancaster factory employed over seven hundred workers. The product was outstanding, long lasting, and had branding so strong that competitors had a difficult time competing with Crystal A.

In the early 1890s, Milton opened a second plant in Chicago to access the western market. Moving that plant to Bloomington, Illinois, to be near the dairies, he then opened up two more plants in Pennsylvania.

By 1894, the company was doing $1 million in sales. Thirty-seven-year-old Hershey brought in his cousin William Blair to manage the business. But Milton Hershey had a temper and Blair quit after one of Hershey’s longer tirades. Blair accepted Hershey’s request to return after Hershey fired Blair’s replacement for tampering with the integrity of Hershey’s product.

At the time, though some women in Lancaster competed for his attention, most didn’t pursue it far, realizing he was putting all of his energy into his business. Hershey, in his thirties, worked from sun up to sun down.

Another man Hershey hired was William F. R. Murrie, a salesman he poached from a Pittsburgh confectioner. Murrie, a man with a giant personality, got out on the road and promised to sell more caramel orders than the factories could fill. When he succeeded, Milton brought him back to Lancaster and put him in charge of the hundred-man salesforce. For the next fifty years, Murrie and Hershey spoke every week, and often dined together.

With a strong team to manage the business, Milton could focus on other things, such as experimenting, his parents, and chocolate.

The World’s Columbian Exposition

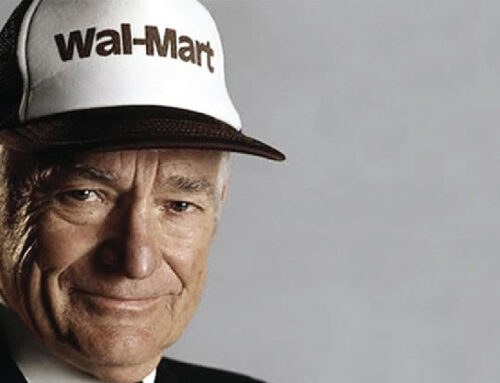

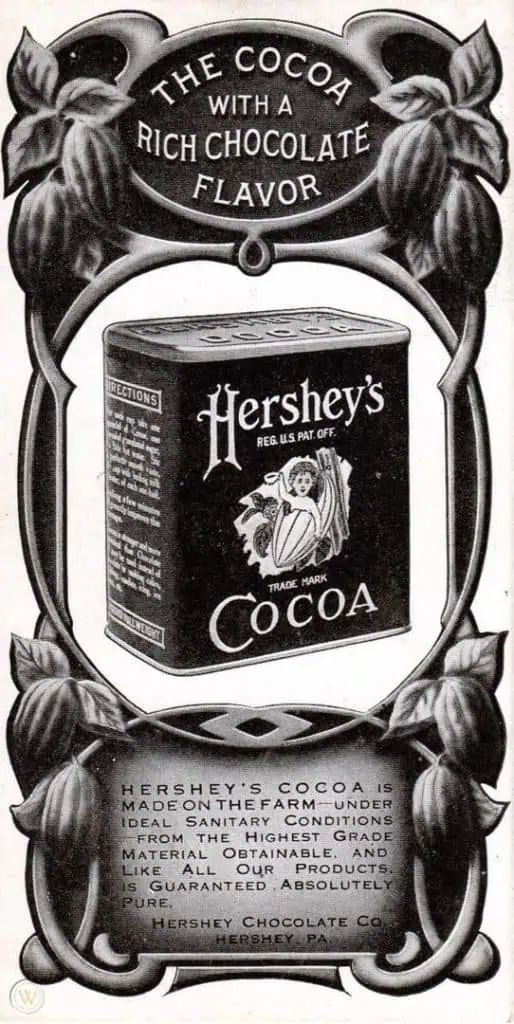

At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Hershey discovered and was in awe of J. M. Lehman’s chocolate producing machines. Continuously returning to study the machines in action, one family story tells that Hershey brought his Snavely cousin to the machines and said, “Caramels are a fad but chocolate is permanent. I am going to make chocolate.”

After the fair, Milton had all of the Lehmann chocolate machines shipped by rail car to Lancaster. Hershey did not want Lehmann to send new machines from Germany. He wanted the exact machines he had studied in Chicago.

By New Year’s Day of 1894, Milton was making cocoa powder for making hot chocolate, baking chocolate, and coatings for caramels.

When the Lancaster Caramel Company was formally incorporated in February of that year, the Hershey Chocolate Company was organized as a subsidiary. Milton owned the majority of the stock, and other holders included cousin William Blair and Uncle Snavely. To grow the chocolate subsidiary, Hershey brought workers from a Swiss chocolate factory to work for him and poached experienced men from other American chocolate mills.

Also in 1894, Aunt Mattie died of pneumonia, Milton bought himself a Lancaster home, and he re-purchased the family’s farmland in Derry Township. Putting an able man in charge of the farmland, he warned him of Henry Hershey, who soon returned and was drunkenly entertaining and annoying the neighborhood.

A wealthy Milton Hershey turned forty in 1897. He was remarkably an unmarried man. Many in the area believed he would spend the rest of his life working, living with his mother, and traveling. He enjoyed trips to New York, Chicago, and Europe to visit important customers.

On one sales trip, Milton and William Murrie stopped at a candy shop and soda fountain in Jamestown, New York. There Milton met Catherine “Kitty” Sweeney, a twenty-five-year-old daughter of Irish immigrants. For months he continued to make the trip to see Kitty. The two continued their courtship when she moved to New York City to work at a ribbon counter at Altman’s, a prestigious New York department store. Milton would regularly travel the four or five hours, presumably by the Pennsylvania Railroad, from Lancaster to see Kitty.

A little over a year after meeting Kitty, Milton stunned his mother when he told her he’d be getting married on his next trip to New York City. And like that, on May 25, 1898, Milton Hershey and Catherine Sweeney were wed in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, with no family in attendance.

Two days later, when the news made the front page of the local Lancaster newspaper, most everyone in and around town, Hershey employees included, were surprised. This was the first time they had heard of Catherine, now Mrs. Hershey.

Selling the Company

In his travels Hershey learned how chocolate was sweeping Europe and eating into Crystal A’s market share. He believed caramel had peaked.

When the American Caramel Company, a recently public company, offered to buy out Lancaster Caramel, Hershey held out. Anxious to sell, but on the advice of his lawyer, Milton continued to wait as American Caramel raised its bid from $500,000 to a mix of more stock and more cash all the way up to $1 million. As part of the deal, Milton Hershey kept the Hershey Chocolate Company subsidiary. On August 10, 1900, the deal was completed, making the American Caramel Company the largest caramel company in the world.

Only a few days later, Milton Hershey put up $150,000 ($4.5 million in 2019 dollars) to “make this chocolate business roll.”

The Hershey Chocolate Company

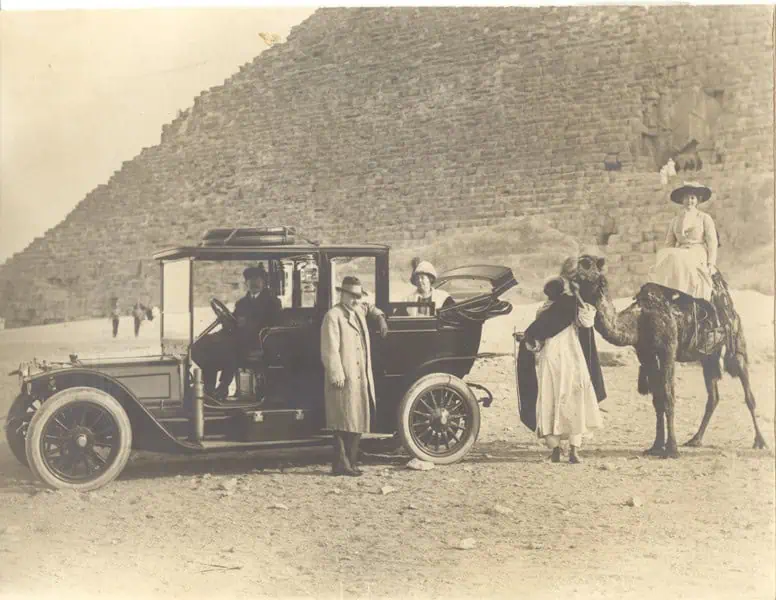

Not long after the sale of Lancaster Caramel, Catherine and Milton traveled to Europe and Egypt—in part to see the sights and in part to get treatment for Catherine’s poor health. Catherine had locomotor ataxia, a term describing nerve damage caused by later stages of syphilis.

In their European travel, with the help of supplier J. M. Lehmann, Milton was able to tour the facilities of a number of chocolate manufacturers. It was also rumored that in this time Hershey worked in European candy factories to better learn their processes.

Back in Lancaster, leasing space from the American Caramel Company, the Hershey Chocolate Company produced all sorts of chocolates: treats like chocolate cigars, cocoa powder, and many more items. Hershey hired trusted men to go work for some of his competitors so that he might learn their methods.

In fact, there was no American chocolate company successfully producing milk chocolate. Pre-milk chocolate, the largest chocolate companies in the United States were Walter Baker & Company in Massachusetts, and Ghirardelli in San Francisco. Only the Swiss knew how to produce milk chocolate and had managed to keep it a secret. But knowing it was possible, Hershey set up an experimental factory on his family farm and brought eighteen to twenty men to work to figure it out.

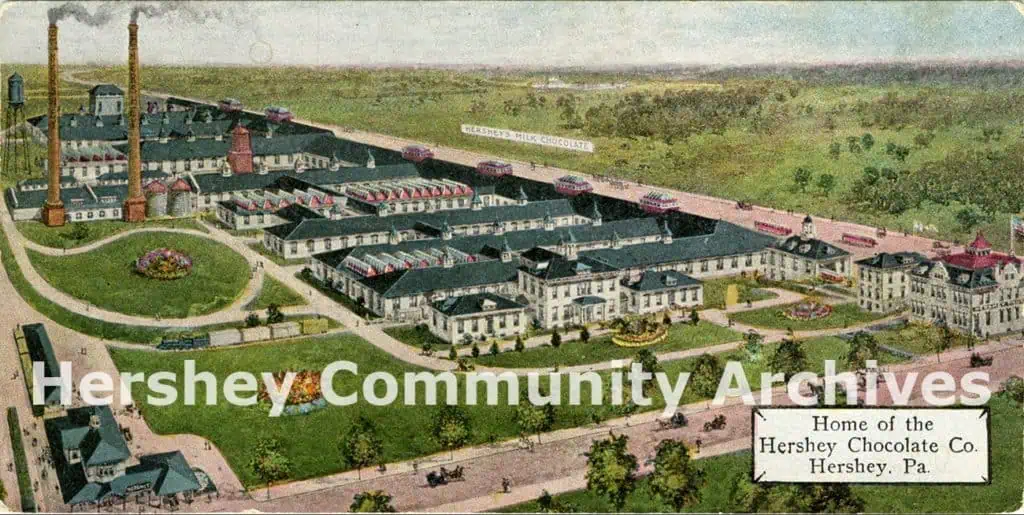

With political corruption on the rise in Lancaster, Hershey decided to move. He visited the nearby town of Palmyra and found a patchwork of family farms on unfertile soil. Within a few months, he had a local real estate agent buy options for over 1,200 acres for a little less than $200,000 ($6.2 million in 2019 dollars).

From the empty farmland, the idea to create a chocolate town was born: a giant chocolate factory, a grid of streets—the two main roads named Cocoa Avenue and Chocolate Avenue—trolley lines, sewer pipes, and more.

By the fall of 1903, the walls for the six-acre factory were beginning to rise. Yet, Hershey and his men still did not yet know how to mass-produce milk chocolate. All attempts had failed or turned rancid after a few days.

After a chemist Milton hired burned a batch, he brought in a worker from Lancaster, John Schmalbach. On his very first attempt, Schmalbach found a way to warm and condense the milk without burning it, creating a mild-tasting milk chocolate that melted in your mouth. Better yet, it could be stored for months without going bad. Unlike the Swiss, who used powdered milk, Schmalbach’s method used condensed milk, making Hershey’s Milk chocolate easier, faster, and cheaper to produce. For this breakthrough, Hershey rewarded him with a $100 bill. This $100 was one of the best investments Milton ever made.

That winter, Milton was traveling with Kitty in Florida when word came that Henry Hershey had died of a heart attack on the family farm. Three days later, the family held a cold February funeral for Henry. Fanny Hershey, who lived in a separate room on the homestead, was finally a widow. Family legend has it that, after the funeral, she wheelbarrowed all of Henry’s treasured books down to the boiler house and burned them.

Despite his father’s shortcomings Milton viewed him as a teacher. A phrase of Henry’s that stuck with Milton was, “If you want to make money, you must do things in a large way.” Milton threw himself into his work.

By the spring of 1904, workers were preparing the milk chocolate for mass production, rail spurs connected the factory to the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, and the village was slowly taking form. Hundreds of new workers came for jobs in building and working in the new factory. Milton was personally involved in everything—from street and shop design to planning the neighborhoods. Kitty would come to watch Milton.

By autumn, workers were able move in and rent modern ready-built homes, equipped with electricity, indoor plumbing, and central heating. Outside of the rental homes, Hershey sold additional lots for people to build their own houses—though the purchaser was subject to a number of restrictions on what they could or could not do. Residents could not build a fence without Hershey’s approval.

The company had a contest to find a name for the new town, with a prize of $100. A woman from Wilkes-Barre submitted the winning name: Hersheykoko. Not long after, the post master declared the name too commercial and the town was ultimately named Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Factory on the Rise

The factory in Lancaster continued to produce a wide range of chocolate products. From 1902 to 1903 sales grew 20 percent, reaching $862,000 in 1903. In 1904, as the company was busy moving to the Hershey factory, sales ended the year at $780,000. By June 1905, production had fully moved to the new factory.

On the east side of the factory a rail spur delivered boxcars of cocoa beans and sugar. By wagon and trolley car, milk came from the local farms and was delivered to the north side of the factory. And on the west side, wrapped and boxed chocolate bars left by another rail spur. In the year ending June 1906, the Hershey Chocolate Company registered sales of over $1 million.

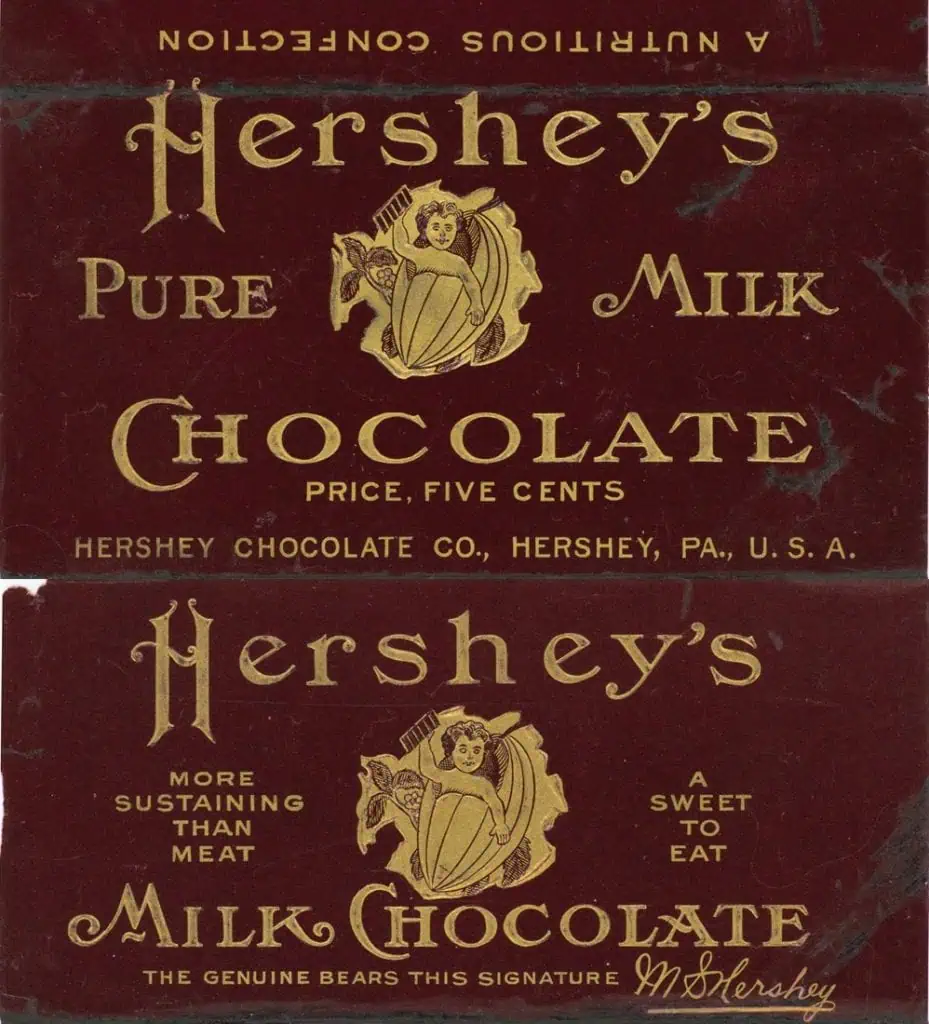

Hershey may have created the first US company to crack the code on mass produced milk chocolate, but it was his thinking behind the five-cent milk chocolate bar that truly set the factory into growth mode. He believed “a fortune could be made for the man who’d achieve mass production at a price everyone could pay.” In a model developed by William Murrie, the Hershey’s sales force called on store owners and bowling alleys, seeking any retail counter with enough space.

Milton was not much interested in the finances and math side of the business, and he let men like the brilliant William Murrie (who became president in 1908) and his executives handle this. Hershey’s focus was on improving the candies and finding and creating new products.

In 1907, Milton introduced a foil-wrapped candy called the Sweetheart. Soon renamed Hershey’s Kisses, the product became a staple of American life and remains so today.

In 1908, Hershey’s Milk Chocolate with Almonds was a huge new hit. Moving from a wide range of chocolate products, Hershey’s strategy was to narrow the number of different products it produced to a few extremely successful ones, driving down unit production and distribution cost.

By 1910, sales topped $2 million as the company continued to grow at a blistering pace. In 1911 sales were $3.6 million and employee headcount reached 1,700. The factory had tripled in size to eighteen acres in floor space (784,000 square feet). Sales crossed $5 million in 1912, the year Milton Hershey paid each of his workers a 20 percent bonus, an unusual move for the time. Despite his occasional temper, Hershey cared for his workers. He’d jump into a production line to help out, willing to work the long twelve- to fourteen-hour days alongside his workers. By the end of the decade, annual sales would cross $20 million.

Trouble in Utopia

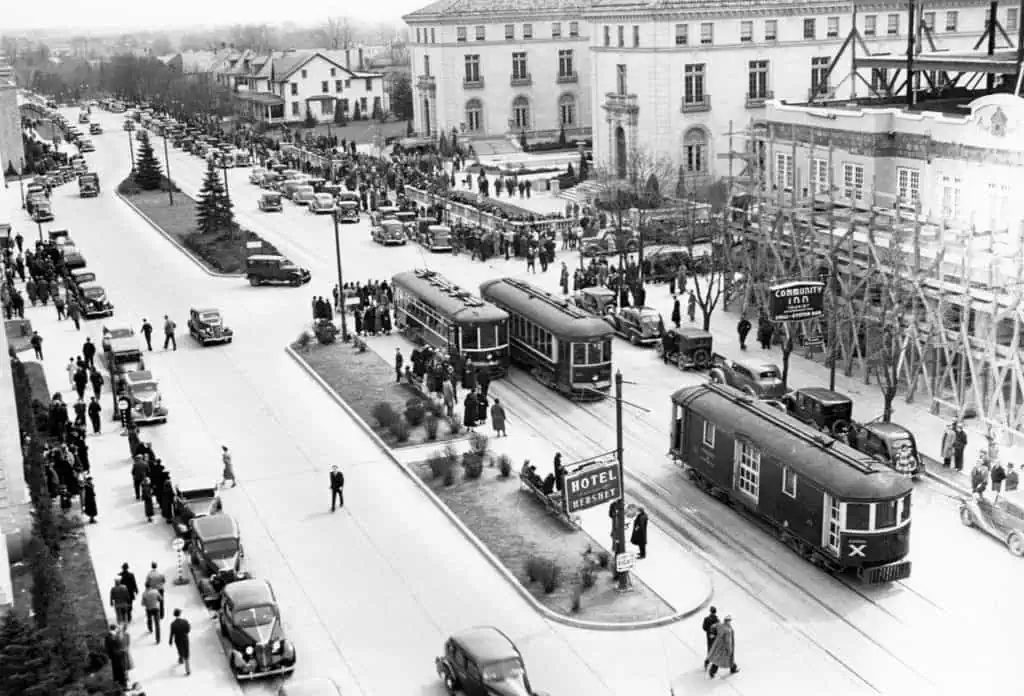

In Hershey, Pennsylvania, a company town, most everything—from the trolley to the department store—was owned or subsidized by the company. The company paid for the schools and the public library; residents, workers, and their families enjoyed these benefits. As a result of the company subsiding much of the town, property taxes were about half the rate of nearby towns.

Milton even built a large park called Hershey Park. Covering 150 acres, the park started as a nature park with landscaped gardens, a large swimming pool, and structures for roller skating. Then came the trolley, a carousel, band organ, and amphitheater. To celebrate the town’s twentieth anniversary, Milton ordered a roller coaster, setting the stage for the modern amusement park, Hersheypark.

Next to the chocolate company, tourism became the town’s second biggest industry. Company executives spurred attendance with post cards, distributed by churches and railroads.

All the growth and success for the company felt a little empty for Milton. At home, Kitty’s illness continued to worsen. By age thirty-seven, she needed a cane to get around. All the money in the world, and all the world’s doctors, could not help her.

Nevertheless, the couple continued to adventure throughout Germany, Italy, France, and Egypt, leaving Murrie to manage the company. For a year and a half, they traveled throughout Europe enjoying their wealth amongst other rich and famous, including J. P. Morgan, and William Wrigley Jr.

By 1912, forty-two-year-old Kitty would need a wheelchair and could no longer cut her own food. Three years later, she could no longer leave the home. Winter of 1915 things took a turn for the worse. Kitty got pneumonia and was taken to Bellevue Stratford Hospital in Philadelphia. The doctor expected things to get better.

At her bedside, Milton asked if he could get Kitty anything. She asked for a glass of champagne. When he returned to her side, Kitty’s appearance was changed. “I think she’s gone,” a nurse said. Milton fell to her side, distraught.

The Later Years at the Hershey Chocolate Company

After Kitty died, Hershey left the day-to-day management of his company to William Murrie and his executives. Milton focused on creating: be it a department store, a zoo for the company town, or an entirely new town and sugar plantation in Cuba.

In Cuba, he wanted a tropical version of his Pennsylvania utopia. After buying up plantations, the town of Central Hershey, Cuba, became established as a reliable source of sugar. Milton had the Hershey Cuban railway built: 120 miles of track connecting his property to ports in Havana and Matanzas. He later built an orphanage in Cuba. And in the late 1920s, the company sold sugar to Coca-Cola.

Sales crossed $20 million in 1918. In 1921, the company took a large loss after Milton made a bad bet on the future price of sugar.

Hershey’s smaller competitors and others in the food industry were spending heavily on advertising; to not do so was considered extremely crazy. Yet the company succeeded without advertising heavily to consumers. Hershey did spend to promote new Hershey products to stores that would sell them. And the company also spent to promote the town and facilities, thereby increasing the brand recognition of the Hershey name.

In the 1920s, Hershey was unchallenged in the solid chocolate bar business. The closest they came to a competitor was when the Uihleins, the Milwaukee family behind Schlitz beer, created Eline’s Chocolate during Prohibition and hired away Hershey salesmen but later gave it up. That decade, Hershey released Mr. Goodbar (1925) and Hershey’s Syrup (1926).

Even as other companies picked up market share in the late 1920s by spending heavily on ads—Baby Ruth (Curtiss Candy Company), Milky Way (Mars Company)—Hershey’s sales continued to soar. Most of the growth came from bulk chocolate sold to bakers and other candy makers, including to Mars for its Milky Way, Williamson Candy for its Oh! Henry, and the Reese Company for its peanut butter cups.

In 1927, the company was restructured into three parts: Hershey Chocolate Corporation, which created and marketed Hershey consumer products; Hershey Estates, which operated the town’s Hersheypark, lands, lumber mills, and quarries; and the Hershey Corporation, which held all Cuban holdings. Hershey Chocolate Corporation became a publicly held company in October 1927, with an offering of common and preferred stock. The company had sales of $41 million in 1929, dipping to $38 million in 1930.

Milton Hershey was glad that a deal to sell the company in 1929 fell through. Stanley Russell at National City Bank of New York had the idea to create the Quality Products Corporation, a food conglomerate including Hershey, Campbell, Heinz, Swift, and others, not unlike General Foods. He had pieced together agreements with Colgate-Palmolive and Kraft and paid for a six-month option on Hershey shares but was suddenly unable to raise the money when the market collapsed that fall.

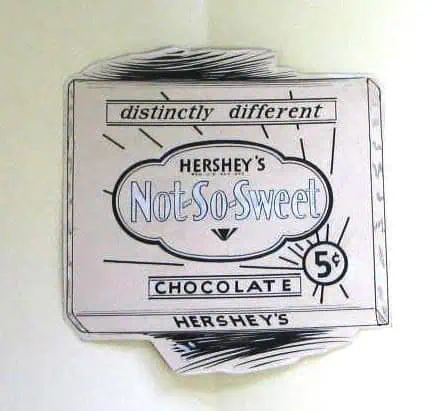

In the Great Depression, sales declined by half, but profits remained strong as raw material prices fell. The Mild and Mellow bar was released in 1933, and the Not So Sweet bar in 1934. The Not So Sweet bar did not sell so well and was discontinued in 1937.

The later 1930s were a time of unionization in America. In 1937, not long after the Communist Party of Hershey, Pennsylvania, circulated a leaflet at the factory accusing the company of slave-driving methods, the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) attempted to unionize Hershey workers and demanded a ten percent increase in pay. The company offered five percent. Milton was shocked by the anger of workers, whom he had treated fairly and created everything in the town for.

In April, close to six hundred workers seized the chocolate factory and began to strike. After five days without progress, farmers who were losing sales of 800,000 pounds of milk a day, along with loyalist workers and army veterans enraged by the strikers running the CIO flag above the American flag, staged a march. Some eight thousand people marched in support of the company. The following day, frustrated farmers and workers gave the strikers an ultimatum: leave the factory by noon or suffer. When no response came, hundreds of farmers stormed the factory with hammers, lead pipes, and fire hoses to beat and haul out the strikers.

For Milton Hershey the violence was the end of the utopian Hershey, Pennsylvania. The company settled on and signed an agreement with a worker’s union by 1939.

On September 14, 1937, Milton Hershey had a minor heart attack. At the age of eighty, he had relinquished the day-to-day management and authority to Murrie, who remained the company’s president. Hershey spent his time inventing and experimenting; most creations were terrible tasting, such as combinations of fruits and veggies and candies. Those who had to try these creations speculated he’d lost his taste buds from years of cigar smoking and did not realize it. At other times Hershey came up with interesting new products, such as victory whip, a non-dairy substitute for ice cream, which he killed off after the dairy industry complained.

Sales at Hershey Chocolate reached $44 million in 1940, and the company was estimated to be producing 75 percent of the chocolate consumed in the United States. Sales nearly doubled to about $80 million in 1944. During the war, Hershey Chocolate Company produced the D Ration for the American armed forces, a chocolate bar that could survive in every possible climate. This gave Hershey access to sugar and supplies, which were rationed during the war. By the end of the war, the Hershey Chocolate Corporation had sent over one billion chocolate bars overseas to support the war effort.

Then, in October of 1945, after suffering from a cough and strain, Milton Hershey died at the age of eighty-eight. Over ten thousand people came to his viewing from surrounding areas to pay homage.

Milton Hershey the Man

According to one of his drivers, Milton was a completely different person when he left Hershey to travel with Kitty. In Kitty, he had found love and was forever changed after her death. He always felt he had been robbed of her.

At the Hershey Industrial School, Milton enjoyed spending time, often breakfasts, with the boys. He took great joy in interacting with the youth.

When it came to business, Hershey had a temper and could turn on a dime when he saw something he didn’t like. Many times, he would catch an experienced worker in a mistake and would have that worker fired. Hershey had little patience, and always wanted the best man for the job. When building the town of Hershey, he quickly removed his friend and longest worker, Lebkicher, from the job of designing the houses after he saw Lebkicher make poor decisions.

He was honest and straightforward in his dealings. After discussions, he would take the time to hear what the other party had to offer, would think about it for a few minutes and accept. There was no haggling at the final deal.

In Hershey, some thought him to be a benevolent dictator. They would recall him in the back of his car touring the town in late 1930s, making notes of unkempt lawns or overturned garbage pails.

He cared for the people and his town. When the Great Depression hit, he put on programs of his own, funding and helping design the beautiful Hotel Hershey in 1933, and the Hershey Sports Arena in 1936, the largest monolithic structure (a single concrete dome) in the United States in which every seat had a clear view. During the Great Depression, residents and workers in Hershey fared better than most of the country.

Legends abound about the wealthy man who paid school custodians to not pick up the Hershey candy wrappers. Yet, having already given away his fortune, Milton Hershey died with little to his name. His longtime friend and colleague Murrie would jokingly offer to pay for his lunch, noting that Hershey’s balance sheet was empty. Hershey’d reply, “I still have my name, and that ought to be worth something.”

The Hershey Industrial School

Established by Milton and Kitty in 1909, the Hershey Industrial School was Kitty’s idea. When she realized she was unable to bear children, the two decided to help kids in need, initially male orphans between the ages of eight and eighteen. With the gift of 485 acres of farmland, including the Hershey Farm, the orphanage was able to take in boys from the surrounding counties, and eventually the entire United States.

The Hersheys took in boys to give the children a good education and stability, something Milton had lacked in his childhood. The first class had ten students. By 1914, there were forty.

Two years after Kitty died, in 1918, Milton Hershey donated his entire fortune which included his ownership interest in the Hershey Company (then valued at $60 million) to the Hershey Trust, the administrator of the school trust. There were no formal announcements, and it was five years before the public learned that Hershey had given nearly everything he owned to the trust. He held controlling seats of the trust until 1944.

Life after Hershey

The Cuban holdings were sold in 1946 to the Cuban Atlantic Sugar Company. The town of Central Hershey, Cuba, was renamed Camilo Cienfuegos in 1959.

Murrie stepped down in 1947. In an interesting bit of history, when William Murrie was president of Hershey in 1940, Forrest Mars teamed up with Murrie’s son, Bruce, to create M&Ms (Mars & Murrie). This move ensured that M&Ms could get a supply of Hershey’s scarce chocolate during the war years. Mars later became Hershey’s largest competitor, passing the Hershey Company up in candy sales in 1973.

In 1963, Hershey acquired the H. B. Reese Candy Company, maker of the popular Reese’s Peanut butter cups, and later Reese’s Pieces, introduced in 1978, and gaining fame in the 1982 smash-hit film E.T., a spot which had initially been offered to Mars. Reese’s remains the top selling candy brand in the United States to this day.

The company acquired Twizzlers in 1977, and under license from British candy giant Rowntree, produces candies such as Kit Kat and Rolo.

The Hershey Trust and the Hershey Industrial School, renamed the Milton Hershey School, live on with over 2,100 students and, as of 2015, a $13.7 billion endowment. The Milton Hershey School Trust owns a controlling interest in the Hershey Company and owns the Hershey Entertainment and Resorts Company. The school is now a private boarding school that has expanded to serve students of all backgrounds. The trust is not without controversy, which includes toxic board battles, compensation issues, and protests over child labor in the chocolate company’s supply chains.

In 2016, an attempt to sell Hershey to Mondelez International (makers of Oreos, owners of Cadbury) was quashed by the trust. As of 2018, the trust owns 3.8 million shares of the Hershey Company common stock, and sixty million shares of B stock, giving it 80 percent of the total shareholder votes.

In 2012, the original Hershey Chocolate Factory closed after 107 years in operation. The company moved to a new facility in West Hershey.

In 2015, the company stepped outside of the confectionary market, acquiring Krave Beef Jerky. In 2017, Hershey acquired Amplify Snack Brands, maker of SkinnyPop popcorn for $1.6 billion, followed the next year by Pirate Brands, best known for Pirate’s Booty puffed rice and corn puffs.

The Hershey Company did $7.9 billion in sales in 2019, generating an after-tax income of $1.14 billion. The town of Hershey, Pennsylvania, has continued to grow, with population reaching 14,257 in the 2010 census.

And so, the creations of the never-satisfied candy man continue to live on. Hershey’s conceptions for Hershey, Pennsylvania, have grown into a town that now sees over three million visitors a year for its Hersheypark. The Milton Hershey School has become one of the wealthiest in the world. And the Hershey Company endures, as it experiments with new candies and foods all while his sweet milk chocolate continues to delight.

Sources

This article was largely based on two books and multiple online sources. The book Hershey by Michael D’Antonio gives a wide range and depth of Milton Hershey and the company he created. The Emperors of Chocolate by Joel Glenn Brenner tells the epic tales of candy giants Milton Hershey and Forrest Mars. And HersheyArchive.org is filled with many great stories of the characters and ideas in this article.