In this American Originals series, we’ve recounted the life stories of men and women who created great inventions and enterprises. None of them had more energy and drive than the shy Julius Rosenwald, a Jewish menswear merchant from Springfield, Illinois. A high school dropout, Rosenwald became a supplier to Chicago mail-order catalog company Sears, Roebuck. By 1900, Rosenwald had become a partner in Sears, eventually taking control of the company.

Over the thirty years of Rosenwald’s daily involvement, from 1897 to 1927, Sears’s annual sales grew one-hundred fold from $2.8 million to $277 million, and profits rose from $141,000 to $25 million. Rosenwald topped this performance by selecting as his successor the equally talented Robert Wood, the man who changed Sears from being a mail-order company into the world’s largest bricks-and-mortar retail chain. We published Wood’s biography here.

Yet Julius Rosenwald was not satisfied with this achievement. No individual we have studied had as much impact on their community: Rosenwald gave away his wealth as fast as he could, supporting cause after cause in Chicago, including the great Museum of Science and Industry. But Rosenwald’s contributions were not limited to cash. In every project, Rosenwald took an active interest, usually leading others to follow in his steps. He found ways to stretch his dollars, and almost always required others to pony up alongside his generous gifts, pioneering new approaches to philanthropy.

Today Julius Rosenwald is largely forgotten, despite his munificence, because he believed in spending his money now rather than leaving a permanent foundation. His most famous effort was his program to build over five thousand school houses and other buildings to educate black citizens in the American South, nicknamed “The Rosenwald Schools.” Today there is a movement to create a national historical park in his honor. This recognition of the great Julius Rosenwald is long overdue. We hope you find this unique man as inspiring as we do. Here is his story.

Beginnings

Julius’s father, Samuel Rosenwald, emigrated from Germany in 1854 at the age of twenty-six, landing in Baltimore. Within two years he had joined fellow German Jewish immigrants the Hammerslough brothers in their successful Baltimore menswear manufacturing business. In August 1857, Sam married their sister, Augusta Hammerslough. The Hammersloughs operated both retail and wholesale menswear businesses in various cities. Sam and Augusta were soon assigned to Peoria, Illinois, then Talladega, Alabama, and finally in 1860 to Evansville, Indiana, where Sam managed the Oak Hall Clothing House. In 1861, the Hammersloughs sent Sam to Springfield, Illinois, where he and Augusta bought a home a block from Abraham Lincoln’s house.

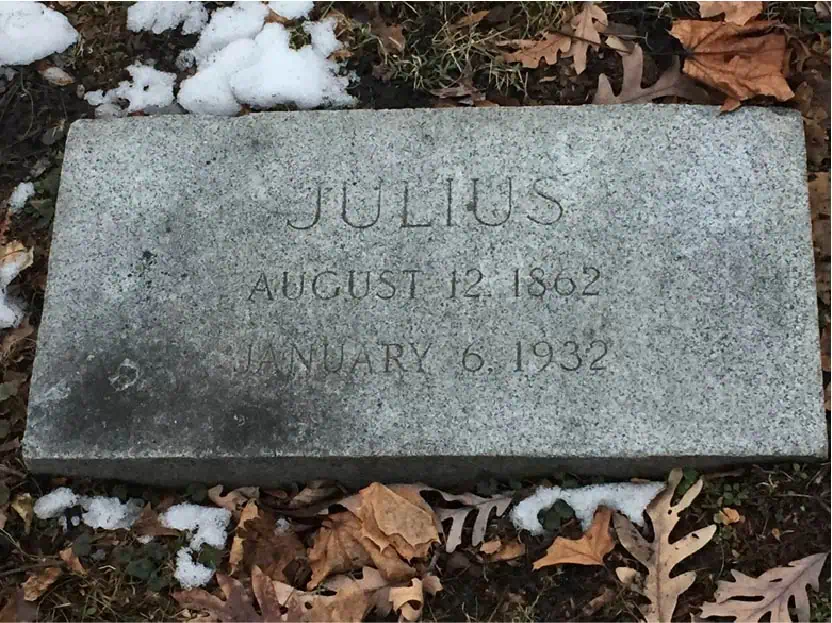

On August 12, 1862, Sam and Augusta welcomed their first child, Julius. He was followed by five surviving children: three brothers and two sisters. Young Julius worked in his father’s store, doing odd jobs and selling menswear. The onset of the Civil War created the need for military uniforms, and with it, the requirement for standardized sizes and mass production. “Ready-to-wear” off-the-shelf clothing became a reality, first in menswear and much later for women. The Hammerslough-Rosenwald businesses prospered.

In 1879, after two years of high school, sixteen-year-old Julius dropped out and moved to New York City to learn the business from the Hammerslough operations there. He was paid five dollars a week as a stock boy, but also took on two other jobs selling menswear in retail stores. Though Julius always regretted not going to college, he learned a great deal in the city. Julius lived with his relatively wealthy uncle Hammerslough, in a wealthier environment than the simple Illinois home Julius came from. Julius attended vaudeville shows with his young friends Henry Goldman, Henry Morgenthau, and Moses Newborg. Goldman’s father founded Goldman, Sachs, a secondary investment firm in the age of J.P. Morgan. Morgenthau became a businessman, then diplomat, his son a well-known New York politician. Newborg was in the menswear business and later partnered with Julius.

After five years in the city, in 1884, twenty-two-year-old Julius and his younger brother Morris opened a retail menswear store in New York, but it was not successful. Julius heard that factories could not meet the demand for “summer clothing,” including seersucker suits, and decided to start a new company making summer clothing. His family and friends liked his idea, and in 1885 Julius, brother Morris, and a friend moved to Chicago where they established Rosenwald and Weil. The business was financed with $4,000 from the Rosenwald and Weil families. The three young men shared a room to save money. Later that year, father Sam sold his interest in the Springfield store and moved his family to Chicago to join his son’s business.

With rising prosperity, in 1890 Julius married Augusta Nusbaum, whom he always called “Gussie,” while she called him “Jule.” Julius was twenty-seven, Gussie seven years younger. Two children soon followed: son Lessing in 1891 and daughter Adele in 1892. Later two more daughters and one son came along, totaling five children.

Julius worked hard and traveled often—to New York on buying trips and throughout the West and Southwest selling his apparel. He pinched every penny, as he did throughout his life. One time, when he made a donation to a charity that stretched the family resources, he came home embarrassed. But Gussie told him she would never oppose any gift he might make to those in need. Thus began a life of philanthropy, despite his frugal nature.

Julius Rosenwald’s dream was to make an income of $15,000 a year: $5,000 to spend, $5,000 to save and invest, and $5,000 to donate to others and charitable causes he believed in. This dream, equivalent to making $500,000 in 2022, turned out to be far too modest.

In 1894, Julius formed a second company, Rosenwald & Company, with financial backing from his New York friend Moses Newborg and his menswear company. The Newborg interests owned half of Julius’s new company.

Meanwhile, Gussie’s brother, Aaron Nusbaum, also a clothing merchant, had gotten the soda water concession at the World’s Columbian Exposition, the world’s fair held in Chicago in 1893. Known as “The White City,” the fair was among history’s most successful and most-attended world’s fairs (relative to the population at the time). In just one long summer season, the concession earned Aaron Nusbaum a profit of $150,000, the equivalent of $5 million in 2022 dollars.

The year 1895, in which two pivotal meetings took place, was the most important single year in this story.

Enter Richard Sears and Sears, Roebuck

Richard Sears, a master advertising copyrighter, had built the second largest mail-order catalog company, following pioneer Aaron Montgomery Ward. Both companies were based in Chicago, the railroad hub of America. Both were growing rapidly as the nation’s farmers realized savings by ordering from the catalogs rather than buying from local merchants, whose merchandise cost more because it passed through wholesalers. In 1895, Sears placed a big order with Moses Newborg for $10 men’s suits (for which Sears paid $6 each). Newborg suggested that Sears buy the suits directly from the Chicago-based Rosenwald & Company, which led to the first meeting of Julius Rosenwald and Richard Sears. Julius, called “JR” in business, became an important supplier to Sears, Roebuck. That year, Sears, Roebuck made a profit of $49,000 on sales of $746,000.

At the same time, Sears’s partner, Alvah Roebuck, wanted to sell his share of the catalog company. Sears was a workaholic; the job stress was too much for the less energetic Roebuck. Seeking someone to buy out Roebuck, Richard Sears found the newly enriched Aaron Nusbaum, JR’s brother-in-law. Nusbaum agreed to buy half of Sears, Roebuck, for $75,000. But Nusbaum did not want to take on the entire investment risk himself, so he approached his friends about investing in Sears and taking part of the stock. At least two men turned him down, before JR, with backing from friends and family, agreed to take half of the shares.

By year’s end of 1895, Julius Rosenwald and Aaron Nusbaum had each invested $37,500 in Sears, Roebuck. Nusbaum and Rosenwald each owned one quarter of the company; Sears owned the other half. Over the next two years, Sears and Nusbaum continued to expand the company, while JR focused his attention on his menswear businesses. Sears continued to write the hard-sell copy of the expanding catalog, while Nusbaum brought business discipline to the company. By 1897, when JR shifted his energies to the company, Sears, Roebuck’s sales had almost quadrupled to $2.8 million, earning profits of $141,000. The company was receiving two thousand orders a day and employed 200–300 workers. By 1898, the catalog was over 1,200 pages. By 1900, Sears, Roebuck was reporting more sales than the older Chicago arch-rival Montgomery Ward.

But Richard Sears was not happy. The man continually struggled with the company’s growth and worried about finances. He told JR and Nusbaum, “I’m going crazy. Here I’ve got the most wonderful business in the world, and it’s running away with me.” He also believed that catalog selling was a scheme that could collapse at any time. Rosenwald, on the other hand, believed in the long-term future of the business.

JR’s first task at Sears was to oversee their clothing business. He found that if the company was out of the size the customer ordered, they would just send the wrong size. Rosenwald sarcastically said, “So why didn’t you send them a watch?” Julius understood that unhappy customers would hurt the company in the long run.

Richard Sears was never focused on product quality, and the catalog included quack medicines and devices. Some catalog illustrations were misleading. The catalog sold a set of furniture that was very successful. The problem was that in fine print it said the furniture was “miniature,” which many customers did not discover until their order arrived. JR worked hard to change these policies, but was sometimes held back by his partners. He advocated for “satisfaction guaranteed or your money back.” As JR became more involved in running the company, Sears, Roebuck adopted these ideas and became nationally known as a trustworthy merchant.

While the company boomed, the three partners argued. Nusbaum was disciplined and business-like, very different from Sears. Rosenwald and Sears disagreed on the importance of product quality. According to JR’s first biographer, M. R. Werner, Rosenwald had “a quick business acumen, a shrewd judgment of the worth of other men and an acute appreciation of the value of their ideas.” The writer went on to say that “Sears was brilliant, Nusbaum was competent, and Rosenwald was a man of insight and diligence. He never lost faith in the business once he embarked in it and learned its possibilities, nor did he desire to dominate or to hamper the activities of other men.”

By 1901, Sears, Roebuck’s buildings covered adjoining city blocks, sales were $14.7 million, profits $776,000, and employment 2,500. But the conflicts between the three men came to a head. The biggest issue was that Sears and Nusbaum could not get along. Sears told the other two men that either Rosenwald and Nusbaum needed to buy him out, or he (Sears) and Rosenwald need to buy Nusbaum out. In what must have been a gut-wrenching decision, JR decided to stick with Sears rather than his brother-in-law Nusbaum. Rosenwald understood the important contribution of Sears’s selling skills.

The irate Nusbaum raised the price he wanted, until Sears and Rosenwald agreed to buy out his one-quarter interest for $1.25 million. He made 33 times his money in six years, a compound rate of return of 79 percent per year. In 2022 dollars, he got $45 million. Nusbaum and Rosenwald never reconciled, which must have been agonizing for Gussie Rosenwald, caught in the middle between husband and brother. But, as always, she stood by her husband.

In the Driver’s Seat at Sears, Roebuck As time passed, Sears became less active in the business while Julius Rosenwald took over active management of Sears, Roebuck. Under his leadership, the company grew, both rapidly and profitably—selling everything from one hundred thousand bicycles to 20 million rolls of wallpaper each year.

JR had an eye for talent, readily delegating responsibility to those he trusted. Otto Doering was in charge of operations, Max Adler managed the merchandise, and lawyer Albert Loeb oversaw administration. All three men contributed greatly to Sears’s success, though Loeb was especially revered by company employees and became JR’s “right-hand man.”

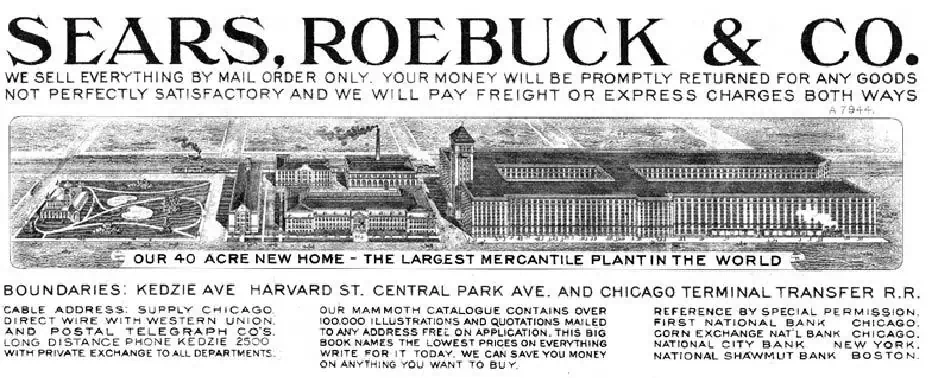

In 1904, Rosenwald and his management team decided they needed to consolidate their big Chicago operations into one giant facility, on Homan Avenue on the west side of Chicago. The massive undertaking was expected to cost about $5 million.

The normal fee for a general contractor who built the structures was 5 percent of cost. But aggressive salesman Louis Horowitz of New York’s big Thompson-Starrett construction firm offered to do the job for one dollar plus cost of materials if Sears was not satisfied with the result. Horowitz’s bosses were unhappy, thinking they would never see more money. When the construction was finished on budget and on time, JR paid Thompson-Starrett the cost of construction and full 5 percent over cost, $250,000—plus a bonus check for $50,000! Within a few years, Horowitz had become president of the giant construction company.

The architects Rosenwald used for his large home and for Sears’s work, Nimmons and Fellows, trusted him so much that they never asked for a contract. The man was as good as his word and never went back on it, even if circumstances changed for the worse.

The company complex itself was massive. Seven thousand construction workers toiled away from January 1905 until the project was completed in early 1906. The floor space totaled 3 million square feet. The main merchandise building where orders were received and filled, usually within twenty-four hours, was three blocks long, one block wide, and nine stories tall. The administration building was topped with a graceful tower. Included inside the buildings was a 400-foot-long railway depot which could hold forty freight cars at a time. Including equipment, machinery, and furniture, the cost totaled $5.6 million, equivalent to $180 million in 2022. In 1906, the number of Sears employees passed nine thousand. The “catalog plant” was beautifully landscaped and had many innovative facilities for employee recreation and education.

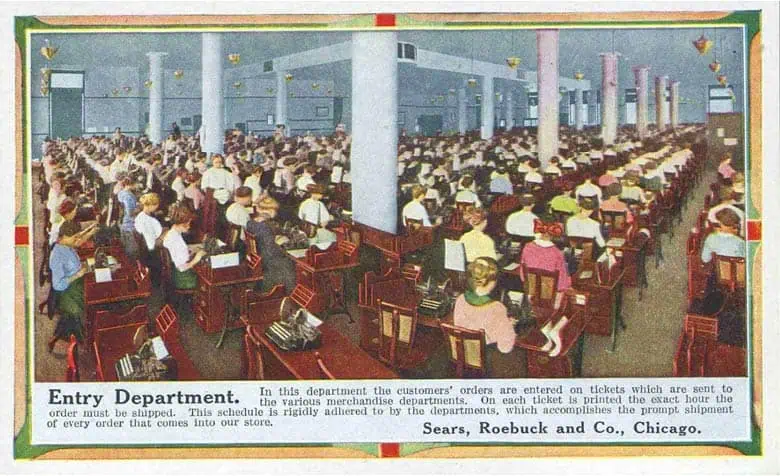

JR and his team innovated at every point in the process of filling orders, which came in at the rate of one hundred thousand per day during the peak Christmas season. Rather than counting orders to see how much work was to be done, each morning a group of workers came in early to weigh the mail, knowing that there were on average forty orders per pound of mail. Sears developed automatic letter openers that could open twenty-seven thousand letters an hour. New conveyor systems were added. Time studies were conducted for every task. When an order was opened, it was assigned a fifteen-minute time slot, later in the day, in which the order had to be completely filled and ready to ship.

After the enormous expense of building the new facilities, JR needed to shore up the company’s finances. He approached his old friend Henry Goldman of Goldman, Sachs to borrow $5 million. Instead, Goldman convinced Rosenwald to take the company public, selling stock to investors across the nation. At the time, it was rare for a retailer to sell stock: only railroads and a few non-railroad companies had public stock. Nevertheless, in 1906 Goldman, Sachs and their friendly competitor Lehman Brothers successfully sold $10 million worth of preferred stock and $30 million worth of common stock, the latter priced at $50 per share.

Rosenwald believed in the company and its stock so strongly that he loaned friends and relatives the money to buy the new shares. Thus began a long tradition of helping friends buy stock and giving stock to charities. Often, JR would guarantee to buy the stock back personally if the price dropped and cover any losses for those who bought the stock. He even gave his barber two shares of stock as a tip, which later were worth $600. Goldman, Sachs and Lehman Brothers rose to prominence among investment banks as they pioneered financing retail and other non-railroad companies. By 1928, before the 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression that followed, one of those original $50 shares had risen in value to $2,800. Rosenwald and his family, who owned about 40 percent of the company, became immensely wealthy. Yet JR remained personally frugal, staying in small hotel rooms. When he first agreed to the stock offering, Herb Lehman of Lehman Brothers visited him in his hotel, where the two men had to sit on the bed since there was no other furniture in the room.

Under JR and his team, the company continuously innovated. In 1906, they added full lists of ingredients to all their food products, before required by law. In 1912, the Post Office introduced parcel post services, and Sears was soon using the new service to send out twenty thousand parcels a day. That same year, the company introduced one of the nation’s first product-testing laboratories, to ensure the best products for the customer’s money.

Richard Sears gradually devoted less time to the company and finally resigned from the presidency and sold his shares in 1909. Because JR did not want to appear to profit from his partner’s departure, he refused to buy the stock, even though he bought more Sears stock at every other opportunity. Goldman, Sachs paid Sears $10 million for his shares. By 1928, those shares were worth $200 million. Julius Rosenwald was now in complete control of the company.

Also, in 1911, JR’s son Lessing joined the company in a menial role. Rosenwald was strongly opposed to nepotism and preferred to give friends and relatives Sears stock rather than give them jobs at the company. But Lessing proved talented and rose in the ranks. Sears gradually opened a series of regional “catalog plants,” starting in Dallas. Lessing Rosenwald ultimately moved to Philadelphia to run the large operation there. He stayed in Philadelphia even when he became chairman of the board of Sears after his father’s death and was a prominent art collector and philanthropist.

Sharing the Wealth

In 1916, Julius and Rosenwald and Albert Loeb developed one of their most important innovations. They introduced one of the first and most comprehensive corporate profit-sharing programs at Sears, covering every employee. Workers could put up to 5 percent of their pay into the program, up to a maximum of $150 per year, which meant that higher-paid executives did not have an advantage. The company added 5 percent of its net after-tax profits to the fund. All of the money was invested in Sears stock. After ten years in the fund, any employee could take out their entire amount, both their own contributions and the money contributed by Sears. If a woman left to get married, she could take her money out after five years. Workers could also borrow against their account, and in cases of extreme need, the company would let them have their money early. Ninety percent of Sears workers joined the profit-sharing program.

These rules and numbers were updated to keep up with changing times. In 1923, JR raised the company’s contribution to one-third of pre-tax profits after taking out preferred stock dividends and a 10 percent return on the par value of common stock. But no matter those numbers, the company contributed a minimum of 7 percent of its after-tax income. Rosenwald said, “Business is business, and what we do here is not charity or benevolence, but business. It is good business to treat people right.”

As an example, someone making $1,200 per year for twenty years could put $1,230 total into profit-sharing. At the end of twenty years, the average amount in their fund would be $17,000. Between 1916 and 1936, 65,000 Sears employees retired, quit, or died. They had put $10 million into profit sharing and taken out $45 million when they left the company. Over time, the Sears profit-sharing plan became the largest owner of Sears stock. The program continued throughout the twentieth century, with the daily stock price posted in the offices at every store and facility.

Troubled Times

World War I led to substantial inflation across the economy. Most commodities and ingredients shot up in price. Then, in 1920–21, prices dropped just as fast, leaving businesses with too much inventory that they had paid the high prices for, while consumer demand fell. Even giant General Motors skirted failure in the brief resulting recession.

Sears was not immune to the recession, having purchased heavy inventories. An unauthorized employee had placed one huge order at high prices, but JR honored the bill, as he felt “morally obligated” to pay it. As prices dropped and consumer demand collapsed, Sears’s sales dropped by one-third and the company posted its first loss, $16.4 million “in the red” in 1921. The stock price fell from $243 in 1920 to $54 in 1921.

Julius Rosenwald dove deep into his personal pocket to save the company. He gave the company back fifty thousand shares of stock, thus raising the value of the shares of others. He also bought the company’s real estate for $16 million, including $4 million in immediate cash. (The company repurchased the real estate in 1931.)

Sears survived the crisis and went on to record sales and profits. How many business leaders today would risk their own wealth to save their company and its investors and employees?

Tragedy struck the company in 1924, however, when Albert Loeb’s son, Richard, and Nathan Leopold, eighteen and nineteen years old respectively, kidnapped and killed fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks for the thrill of it. All three families were neighbors of the Rosenwald family. The incident was the “crime of the century,” later portrayed in print and film.

As the years went by, Julius Rosenwald spent more and more of his time and bountiful energy on his charitable causes, leaving day-to-day management to his talented associates. In 1927, his talented successor, Robert Wood, took over the presidency of the company. JR remained chairman of the board and very interested in the company until his death five years later.

In his leadership of Sears, it’s clear that Julius Rosenwald was an exceptional businessman and leader. Both at Sears and in the many causes enumerated in the following paragraphs, JR had a passion for the succinct and the factual. He was known as a great listener, seeking ideas from everyone. People said he was “refreshingly direct and honest.” He believed that the keys to business success were “energy, imagination, and courage,” all attributes he personified. Above all else, Rosenwald, like other successful merchants, was able to “put himself in the shoes of others.” He said, “I am always selling merchandise to myself. I would stand on both sides of the counter.”

His Gifts Overfloweth

Julius Rosenwald said, “It is unselfish effort, helpfulness to others that ennobles life, not because of what it does for others, but more what it does for ourselves.” Few men or women have lived their beliefs, “walked the talk,” or “put their money where their mouth is,” as much as this man did. The level and diversity of his philanthropy was remarkable. The following paragraphs only scratch the surface of Rosenwald’s contributions and donations.

JR was never a passive donor. He took on leadership roles and committee positions in every cause he bought into. He thought long and hard about every issue and traveled the country promoting those causes. And everywhere, he leveraged his money, requiring others to contribute alongside him. He did not want any charity to become wholly dependent upon him. He wanted others to have “skin in the game.”

Rosenwald’s donations were triggered by the people he met. Reformed Jewish Rabbi Emil Hirsch introduced him to many of Chicago’s needs, as did Mrs. Rosenwald (Gussie). JR helped finance Jane Addams’s famous Hull House and Grace Abbott’s Immigrant Protection League in Chicago. Like many American Jewish leaders, Rosenwald was not a Zionist, but he still donated to the Jewish needy in Russia and in Palestine.

Rosenwald cared deeply about the city of Chicago and its future. He was the largest single taxpayer in Cook County and supported many educational institutions. When city leaders developed a long-term plan for the city in 1909, JR was one of the leaders and most active businessmen. He believed in better government, heading the Bureau of Public Efficiency to investigate government spending and corruption. He backed reform candidates for mayor of Chicago. This caused many politicians to come out against him, but that never stopped JR. At the same time, he could work even with those who fought him, if it helped his causes. Rosenwald was not a man to burn bridges.

Julius Rosenwald was not fond of giving speeches, but he made them anyway to support his ideals. He wrote newspaper opinion pieces and spoke on national radio networks. He urged others to follow his lead, and donate alongside him, with great success. Despite being a high school dropout, JR’s words were concise, articulate, and to the point.

For his fiftieth birthday in 1912, JR gave away $687,000. From that year on, his annual donations averaged $500,000 ($16 million in 2022 money). Included in the 1912 gifts was $250,000 for a building at the University of Chicago, not far from his home. The University named the building Rosenwald Hall while JR was overseas. But JR did not like his name on monuments and would have stopped it had he been in Chicago. Upon his return, he decided not to fight the naming, as that would embarrass the university. JR had a special interest in the work of the university’s Egyptologist, James Breasted, visiting him at the archaeological digs in Luxor, Egypt. He joined the university’s board of trustees in 1912 and was one of the most active members for twenty years, until his death. By that time, his contributions to the university totaled $4.5 million, including $2 million for the Burton-Judson dormitories.

Crossing Color Lines

Rosenwald became very concerned about the poverty of the American South and the plight of American blacks. In 1916, he donated $100,000 to the Tuskegee Institute, run by his friend Booker T. Washington. The same year, he financed the building of eighty schools for poor blacks in the South. As word of these schools spread, Rosenwald wanted to do more, at first backing another three hundred schools. But he only put up one-third of the cost, requiring the state put up one-third, and the local community one-third (which could include land, labor, and materials contributed by locals). Local blacks contributed millions to this program. At the time of his death, over five thousand schools had been built in fifteen states, with a capacity of more than six hundred thousand students. The schools were colloquially called “Rosenwald Schools” and the students and teachers called him “Cap’n Julius.” He became a folk hero and his picture was on the wall in each school, alongside those of Abraham Lincoln and Booker T. Washington. Millions of lives were improved by this program.

JR also donated $1.25 million to black colleges and universities in Washington, D.C., Atlanta, Nashville, and New Orleans. He helped fund twenty-four YMCAs in black neighborhoods. One of JR’s favorite projects was the Michigan Boulevard Garden Apartments, an all-black residential complex with modest rents, and retail and banking facilities, foreshadowing more recent developments. The complex, with over four hundred apartments, was also called “Rosenwald Courts.”

In backing the schools and many other causes, Rosenwald was roundly criticized. The experts said, “Negroes cannot be educated,” but JR did not buy it. In both business and philanthropy, he had firm beliefs, was ready to fight, and stood his ground. It was said that he actually enjoyed a good fight when he knew he was right.

Beginning in 1928, one of JR’s funds handed out over $400,000 in $1,000 and $2,000 “fellowships,” which went to rising stars in music, art, literature, science, and academia. The vast majority were black Americans. These grants helped propel many to success, including James Weldon Johnson, Marian Anderson, Ralph Bunche, W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, and John Hope Franklin.

Broad Visions JR also loved his country. In World War I, President Wilson asked him to serve on the Commission of the Council of National Defense. In this role, he was assigned to secure the food and supplies for the nation and the military. He oversaw the spending of over $700 million. Sears had a long tradition of helping its suppliers by buying commodities in quantity on their behalf. For example, the company bought rubber for its tire suppliers or fabric for the clothing companies, at low prices in huge quantities. JR applied this same idea to government purchases, saving $1.5 million on the cost of shoes alone, buying leather up front. He traveled to France to meet the troops, where he shook their hands and wrote down their names. If they were from Chicago, he wrote letters to their parents upon his return home.

Rosenwald backed an immense variety of ideas. He helped finance Admiral Byrd’s Antarctic expedition, financed newspapers and the magazine Harper’s Weekly, and invested in the first true American “motion picture palace,” built by Sam Katz and A.J. Balaban not far from Sears’s headquarters. JR funded six free dental clinics in Chicago’s public schools. He was often ahead of his time, joining the Committee on the Costs of Medical Care, studying a problem that still plagues America. He spent hundreds of thousands of dollars supporting hospitals and nursing education. (The American Medical Association called some of his ideas “socialist,” but Rosenwald did not back down.)

Julius and younger son William had visited Munich, Germany, in 1911, where the eight-year-old was absorbed by the Deutsches Museum. This great museum showed how industry and machines worked and had many exhibits that today would be called “interactive.” JR was most impressed, and determined that the United States, especially Chicago, needed such a facility to educate the public. By 1926, he had convinced Chicago leaders of his idea and work began on what became the Museum of Science and Industry, in the old Fine Arts building from the 1893 fair. JR resisted all efforts to name the place the Rosenwald Museum and donated $3 million towards the exhibits. For decades admission was free, thanks in part to dividends on the Sears stock he donated. Still one of the most-attended museums in the world, it inspired many other American cities to build science and technology museums.

In 1929, the will of Conrad Hubert called for his executors to name three “eminent men” to dole out $4.5 million. Hubert was the inventor of the flashlight among other things, and the founder of Eveready batteries (now called Energizer). His executors picked former President Calvin Coolidge, former Governor of New York and Presidential Candidate Al Smith, and Julius Rosenwald. Applying JR’s beliefs, the bequest was leveraged up (by requiring others to also contribute) to have a philanthropic impact of over $15 million.

Today we might say that Julius Rosenwald had “a sense of urgency.” He wanted to make a difference now. He often required his money be spent soon, not put into a long-term endowment where only the interest income could be spent. He urged endowments to spend both interest and part of the principal. JR detested the idea that he would leave a foundation where his “dead hand” spent the money. When he died, all his money was required to be spent within twenty-five years, and the people who ran his funds spent it all within sixteen years of his death, which would have made him happy. Rosenwald was always outspoken about these and other ideas about philanthropy. In 1929 and 1930, he wrote two widely circulated articles for the Atlantic Monthly magazine full of his sometimes contrarian thoughts. JR said he did not like “sob stories” or giving for giving’s sake.

His own philanthropy was intended to cause lasting change, to fundamentally alter society for the better.

Julius Rosenwald the Man

Nothing in JR’s life was as important as his family. When on the road, he would call, write, or wire both his wife and mother every day. Every morning when he was in Chicago, he would walk his children to school, then stop by his mother’s home before going to work. He was always home for dinner, leading a lively conversation with his children and his many visitors from around the world. Those visitors included bankers, writers, singers, actresses, social workers, and rabbis. At Christmas, he and his family hand-packed hundreds of gift packages filled with candy for poor children. While he was concerned that being rich would spoil his own children, he nevertheless showered them with toys from Sears.

Rosenwald’s wife, Gussie, was always at his side, probably the most important influence in his decision-making. Like her husband, Gussie had no use for prestige or ostentation. But she did believe in charity, both JR’s causes and her own.

Julius Rosenwald’s door was always open to any Sears employee who wanted to talk to him. Most days when he was in Chicago, he bought lunch in the Sears dining hall for ten people from around the company. He loved meeting people, whether presidents and kings or the “guy on the street.” His car was always filled with all the Chicago newspapers and his pockets full of clippings, because “they tell the stories of people.” He stayed at the White House in the presidencies of both William Taft and Herbert Hoover, a friend he admired for his humanitarian work. JR was adamant that being rich was no indicator of character or quality, that he had been fortunate in life while others with great talent were just unlucky. He said, “Do not be fooled into believing that because a man is rich, he is necessarily smart.”

Two of the most striking aspects of JR’s personality were his humility and his passion for life and sense of humor.

Rosenwald never seemed to take credit for any of his many accomplishments. In later years, he said, “To say that I had vision and insight in going into Sears is nonsense. . . . I saw a good chance. . . . It was simply a lucky chance that the business developed along such a scale. . . . We ran it efficiently and worked hard and it made money . . . the subsequent economic developments of the country have made it into what it is.” Throughout his life, in every word he spoke or wrote, Julius Rosenwald denied that he was anything special. He went so far as to say, “I really feel ashamed to have so much money.”

JR lived life to the fullest. He loved football and attended every game he could. His “eyes glowed” as he showed people through “the store,” as he called the giant Chicago facilities the company built. Each evening over the family dinner table, JR entertained his growing family by reading letters from customers. When it was reported that the Amir of Afghanistan read the catalog daily, JR had a copy leather-bound and sent to the Amir, who had died two years before it arrived. The Rosenwald home welcomed visitors from around the world.

JR was always ready with a joke and loved to laugh. When a prominent author handed JR his latest book, JR gave him a Sears catalog, saying, “I am prolific, too, in a way. You may find my book a trifle disconnected, but there is some good stuff in it.” When a distinguished visitor from Europe mentioned that he had never seen a catalog, JR went around the home to find one. The only one he found was a Montgomery Ward catalog, a story he loved to repeat. When touring the front in World War I, JR was in full military garb, but without rank. He was lined up in the midst of several generals who introduced themselves one by one. When it came JR’s turn, he introduced himself as “General Merchandise.”

Rosenwald was “congenitally optimistic,” a common trait among successful entrepreneurs. He shook worry off quickly and did not waste time and energy fretting over past decisions or things he could not control.

Julius Rosenwald was above all else a man in motion, “radiating vitality.” He hated “rest resorts,” even when the doctors prescribed them. He just wanted to get back to Chicago and into action. He arose early each day to play tennis. While he enjoyed driving (and apparently drove fast), he normally was chauffeured. Most days, he made several trips from his west side office to downtown Chicago, working on his many projects and meeting with city leaders. JR would jump out of the car before it came to a stop, running to his next appointment. He was not tall, but still climbed stairs two steps at a time. Between meetings, he would change clothes in the backseat to save time. He reportedly loved to catch trains at the last minute.

Rosenwald’s frugality was legendary. He had “an abhorrence of waste or extravagance.” He worried that his money might make him soft and dependent on others for personal services. He kept his cars until they fell apart. In everything he did, Julius Rosenwald wasted no time, no effort, and no money.

End of the Road

In May 1929, JR’s wife of thirty-nine years, Gussie, died—a terrible blow to him. Yet he carried on. The next year he married Adelaide Goodkind, mother-in-law of his son Lessing. But not much time was left: by the end of 1930, the sixty-eight-year-old Rosenwald was effectively an invalid.

As JR approached the end of his life, he did not slow down. His impatience intensified, as he worried about the “lack of time to accomplish the largest possible number of important things.”

Julius Rosenwald’s fortune shriveled in the stock market crash and Depression as Sears’s stock fell from $200 per share in 1928 to $30 by the end of 1931. Yet, in his rush to do good, he gave away hundreds more thousands of dollars in 1930 and 1931.

In January 1932, Julius Rosenwald departed this world, the world he loved so much and tried to make better.

Despite the fall in his wealth, JR’s will set aside millions more, so the organizations he supported would not be “embarrassed by his death.” Due to the Depression and the drop in Sears’s stock, his estate had a net worth of only $17 million—$48 million in assets minus $31 million in debts, including obligations to charities. His executors were smart enough not to sell Sears stock at the depressed prices, instead borrowing millions to cover Rosenwald’s obligations until the Sears stock rebounded.

During his lifetime, Julius Rosenwald gave away an estimated $63 million, not including gifts to friends and family. He only wished that he could have done more.

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.