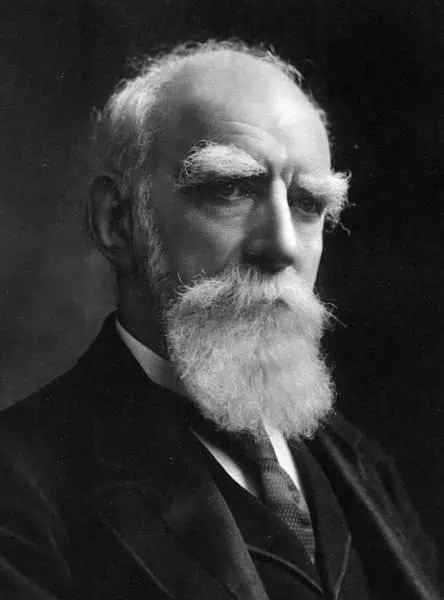

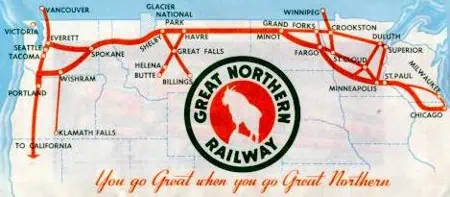

The American railroad system played a critical role in the growth and development of the United States, especially the opening of the western frontier. The western railroads, which continue to serve society today, were often built with massive land grants and government subsidies. But the most successful of the great transcontinental railroads, the Great Northern Railway, was built without such government help and grants. The Great Northern was the lifelong project of one man, James J. “Jim” Hill. Jim Hill left poverty in rural Ontario after his father died when the son was only fourteen years old. He landed in St. Paul, Minnesota, where over the next fifty years he did more to shape the northwestern United States than any other single person. This is his story.

Beginnings

Jim Hill’s parents, James Hill and Ann Dunbar Hill, were both born in Ireland but had emigrated to Canada and were married there in 1833, when Ann was twenty-eight and James twenty-two. They had been preceded by relatives who had received land grants in rural Ontario from the British government, usually for military service. James (the father) and Ann had a son named James who died as an infant. Daughter Mary came along in 1835. Their second son, also named James and the subject of this story, was born on September 16, 1838. One more son, Alexander, completed the family.

The family farmed in a then remote area of Ontario, near the town of Rockwood, not far from today’s city of Guelph. The father was a Baptist, the mother a Catholic, but the boys were raised with Quakers. Key to young Jim’s education was a Quaker teacher from England, William Wethereld, who insured that Jim learned practical skills like geometry and surveying. Wethereld encouraged the boy and was never forgotten by him. Jim also excelled at writing and loved to read literature, starting with his family’s volumes of Shakespeare. He played hooky from school to absorb Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe.

Jim became an expert fisherman and an excellent shot with a rifle, as befit life on the frontier. When he was nine, his handmade bow snapped and propelled the backend of the arrow into Jim’s right eye. Vision in that eye was lost forever, but most people never noticed. This handicap never slowed down Jim or his voracious reading and later continuous letter-writing.

When Jim was ten, his father gave up farming to open an inn and tavern in Rockwood, exposing the boys to song, dance, rough men, and rough women. But on Christmas day, 1852, when Jim was fourteen, his father died after a short illness. Jim, who had “a nervous drive to keep busy,” became the family breadwinner. His formal education ended. His first job was clerking in a general store in Rockwood for a dollar a week. Jim was an eager student of double-entry bookkeeping and became knowledgeable about trade, merchandise, and customer preferences.

At thirteen, Jim, impressed by the exploits of Napoleon, chose the middle name “Jerome” after Napoleon’s brother.

Jim’s mother gave up the inn and tavern in 1854 and moved the family to Guelph. Jim clerked in a grocery store, continuing his “real-world” education. By 1855, with his sister married and his brother taking care of his mother, seventeen-year-old Jim determined that rural Ontario did not hold the opportunities he sought. Jim had a lifelong passion for the possibilities of Asia and the Asian trade and hoped to get to the Orient. But first he needed to see America, where many Canadians were moving. He used his meager savings to board a train and head east to “see the world.” In his first stop, New York City, he had his pocket picked but had kept some money aside. He then proceeded to Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, Savannah, and Pittsburgh before returning to New York. By July of 1856, after stopping in Chicago, he found his way to St. Paul, a bustling city of ten thousand in the Minnesota Territory. (Minnesota became a state two years later; St. Paul its capital.) The business opportunities appealed to Jim, and the weather felt like home.

An Education in St. Paul

The great appeal of St. Paul was its position at the head of the Mississippi River on one side, and access to the valley of the “Red River of the North” on the other. As one of the few economically important north-flowing rivers in the world, along with Egypt’s Nile, the Red River of the North begins in Minnesota and the future North Dakota and flows through forest-covered rich soil into Winnipeg, in Canada’s Manitoba province. Before farmers began to settle the area, it was an important route of the fur trade and North America’s oldest company, the Hudson’s Bay Company (founded in 1670), which dominated the fur trade.

At this time, Canada above the Great Lakes—the far reaches of western Ontario—was nearly impassible, full of marshlands, winter snow and ice, and summer mud. Any trade coming from eastern Canada’s populous Toronto and Montreal that headed to emerging western Canada and the Pacific coast of British Columbia could only move west through Chicago and St. Paul, then up to Winnipeg. As Canada began to unify as a nation, and to subjugate the native Americans and French trappers of the west, even weapons and government officials moved along this path through the United States.

St. Paul was the key to all this trade, and Jim Hill knew it. Furs moved south while manufactured goods and commodities moved north through St. Paul. By 1856, 837 boats plied the Mississippi as far north as St. Paul, filling the riverfront docks. The season began in April after the river’s ice had thawed and lasted until the late fall.

Jim, age seventeen, quickly got a job with the established firm of Brunson, Lewis & White, passenger and freight agents for the Dubuque Packet (steamboat) Company on the Mississippi River. He was assigned increasing responsibilities due to his elegant handwriting (in the days before typewriters) and his skills at writing letters and keeping neat record books. But he was equally likely to use his strength to stop a fistfight on the docks or calm a drunken passenger.

Furs moving south from Canada and manufactured goods moving north from the United States and Europe traveled to and from Winnipeg by the Mississippi River to St. Paul when the river was open, by horse-drawn carts or sleds to the Red River, then again by boat on the Red River to Winnipeg.

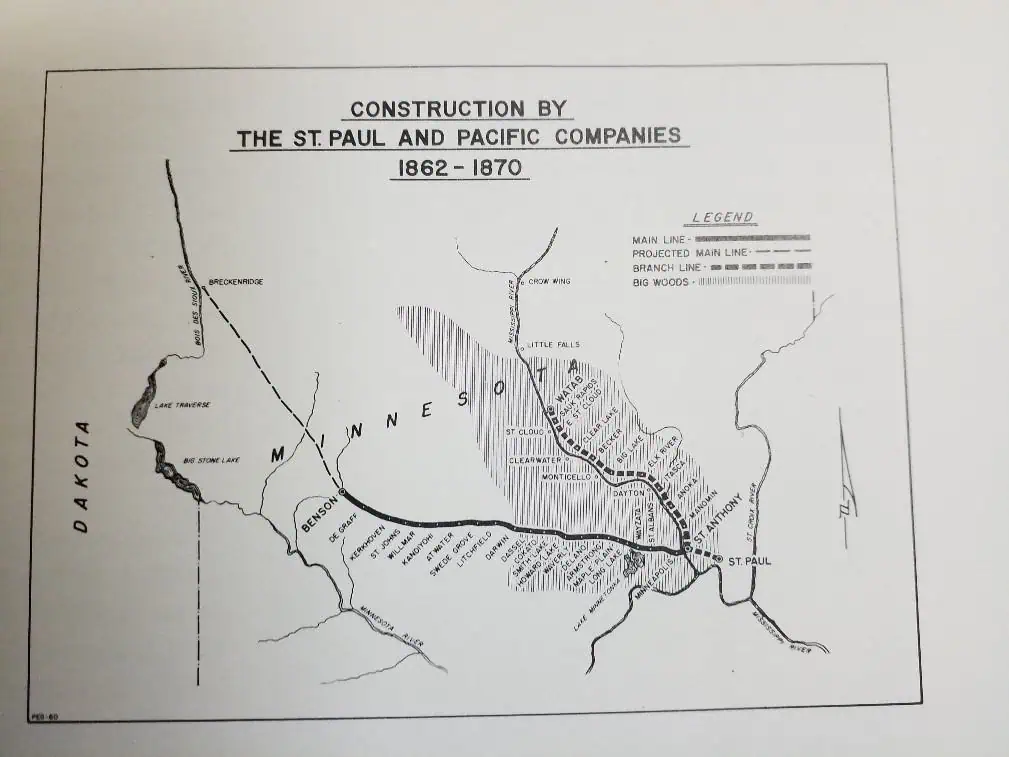

In 1856, the tiny and badly built St. Paul and Pacific Railroad began to build very gradually toward the Red River. Moving passengers and especially freight between the steamboats and the railroad and carts became a big, busy business.

Jim was at the heart of the freight forwarding activity in St. Paul. He moved from Brunson, Lewis & White to a wholesale merchant firm in 1859, then in 1860 to Borup and Champlin, wholesale grocers and forwarding and commission merchants. He was associated with these experienced traders for the next seven years, learning every aspect of “the trade.” Every inbound and outbound freight shipment had to be unloaded, tracked, and reloaded as it moved through St. Paul. Jim Hill excelled at this and impressed and befriended his elders and gradually became partners with them in various ventures. Most became friends for life, even when he was a competitor in one business or another.

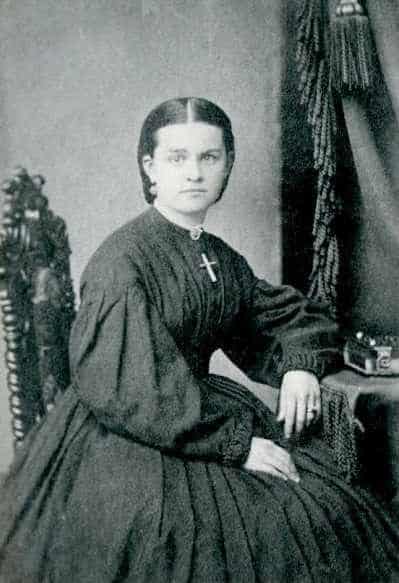

In 1864, Jim became engaged to Mary Mehegan, a devout Irish Catholic whose father had died when she was eight. On August 17, 1867, the twenty-nine-year-old James Jerome Hill married his twenty-one-year-old bride. The couple was prolific, producing three sons and five daughters.

Jim Hill built warehouses to hold the products of Minnesota’s burgeoning flour milling industry during the long winter until the Mississippi opened in the spring. He developed freight terminals. In 1872, with prominent Minnesota businessman and fur trader Norman Kittson, he started a steamboat business on the Red River, the Red River Transportation Company, which soon dominated that trade. Jim introduced the use of more expensive but efficient coal to replace wood for use in boats and locomotives, creating the very profitable Northwestern Fuel Company in 1875.

Hill was indefatigable. He continually talked to customers, learning the needs of shippers and recipients. He ventured by sled into Canada, one night surviving the subfreezing temperatures only by sleeping next to his sled dog—he took the dog home afterward out of appreciation. He set the broken leg of one of his scouts by rigging up a rope on a wagon wheel and sitting on the man’s chest while he pulled hard. The snow, the ice, and the extremes of weather never interfered with his quest to “know the land” and the opportunities it held. He did “whatever it took.” One of his stock phrases was that he wanted to be “where the money is being spent.”

Over time, Jim became enthused over the potential of railroads. He had an insight that no one else had. Others saw that trains would allow settlers to get to the Red River Valley a few days or weeks earlier than by trail and water. On the other hand, Jim realized that by opening the frontier all winter as railroads could do, settlers arriving in February could get in one more planting cycle than if they did not arrive until April when the rivers opened. So, in fact, they’d actually gain a year, not a few days or weeks, in their ability to produce grain and make a living. He knew that railroads would kill his highly profitable steamboat business, but also understood that railroads would better serve the people and “develop the territory.”

As rail connections were established from Chicago, the Mississippi’s seasonality was no longer a limiting factor for freight going to and coming from the east and south, but much was still left to be desired for traffic north to Winnipeg and west to the Dakotas and western Canada. As a freight agent, Jim became friendly with the key eastern railroads and their managers. He was a keen observer and asked many questions; he learned everything he could about the railroad business. Jim and his friends began to eye the flailing St. Paul and Pacific Railroad.

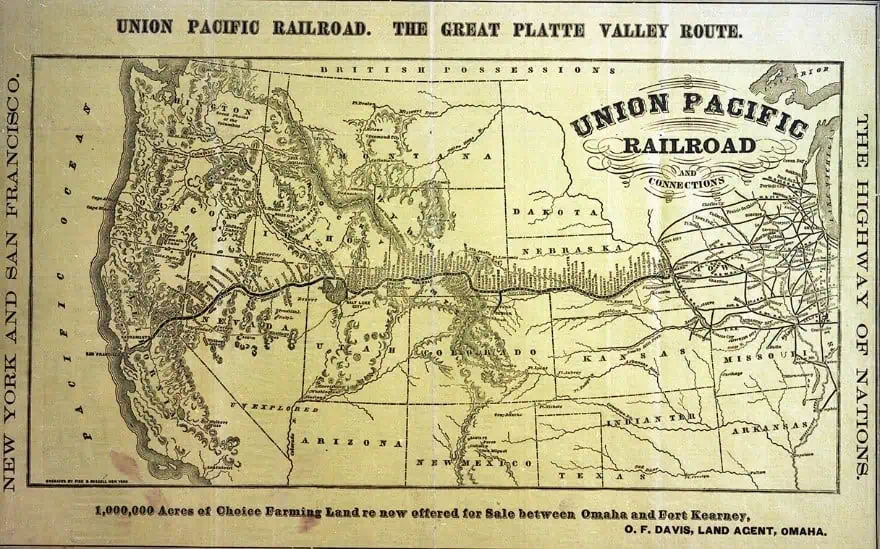

The Transcontinental Railroads

The life work of Jim Hill can only be understood in the context of western railroading. The federal government realized the importance of connecting the Pacific coast with the rest of America but believed this could only be accomplished with help from the government. This help came in the form of loans for each mile of track completed and massive land grants, land which the railroads could sell to settlers across the west. Over time, three transcontinental routes were selected: a central, southern, and northern route. The first to be completed was the central route, when the Union Pacific worked westward from the railhead at Omaha and the Central Pacific worked eastward from Sacramento, later extending to Oakland on San Francisco Bay. The two railroads met at the Golden Spike ceremony in Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869, which was heralded across the nation.

The Union Pacific builders had received land grants on alternating sides of the track totaling at least twelve million acres, the Central Pacific almost seven million acres. The Central Pacific’s sister railroad, the Southern Pacific, got fifteen million acres for the southern transcontinental, finished in 1883.

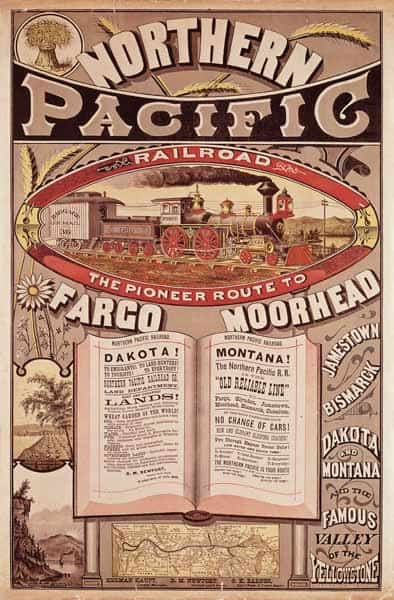

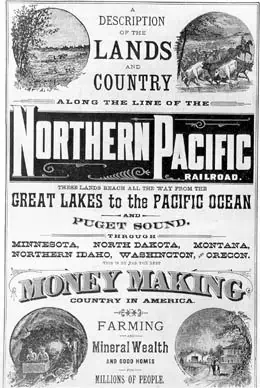

The largest grant, almost forty million acres, went to the Northern Pacific. This railroad, ultimately stretching from the port of Duluth on the Great Lakes to Seattle in 1883, was particularly troubled. Funded by Wall Street wheeler-dealers, it went bankrupt in 1873, as it was to do again twenty years later.

These subsidized railroads were not well-built. Sometimes the builders were in a hurry to make deadlines set by the government in order to earn their subsidies, and they built short routes that rose and fell with the terrain rather than minimizing the hills that are the bane of efficient train movement. At other times, when they were not up against deadlines, the transcontinentals built extra, needless mileage to get more loans and land grants, which were based on the number of miles built.

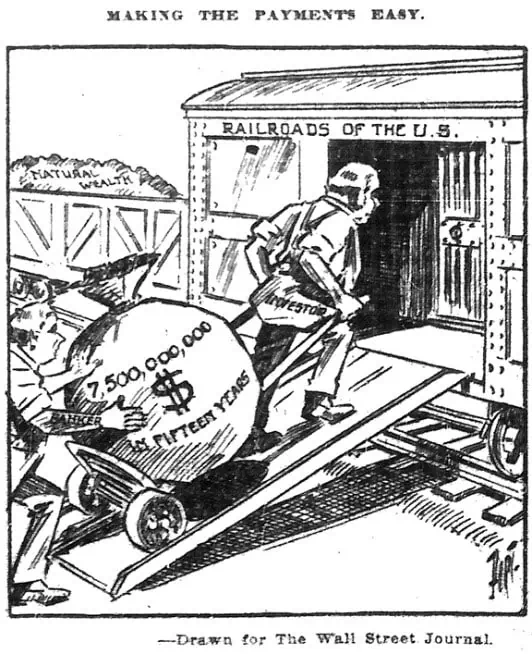

The promoters of the railroads created separate construction companies which they owned. They did not believe the railroads themselves could be profitable, so they tried to make all their money during the construction phase. These construction companies overcharged the railroads and used cheap rails and other materials. A national outcry resulted when it was revealed in 1867 that the Union Pacific’s supposedly independent construction company, the Credit Mobilier of America, was controlled by the railroad’s officers and had bribed congressmen to support the subsidies. Through financial games, the directors of the Credit Mobilier of America hid profits of over $20 million ($370 million in today’s money). These and other shenanigans gave the railroads and their builders a bad name, which would haunt James Hill (undeservedly) throughout his life. But it also gave Hill the opportunity to acquire railroads and “fix them up.”

The Great Northern Railway

Jim Hill saw the little St. Paul and Pacific as a golden opportunity, a railroad that could be profitable if managed right. Gradually building from St. Paul west toward the Red River and north toward Winnipeg, this small north-south line was beset by the same evils as the transcontinentals. Built slowly and poorly, with cheap iron (not more durable steel) rail, the line received about 2.5 million acres in land grants. Even with this gift, the railroad was not profitable and had not reached its planned destinations. By 1862 the company was bankrupt. A new owner came along, but by 1870 had made little progress. The Northern Pacific, working on building to Seattle, bought control of the St. Paul as a feeder railroad. Despite its huge land grants of almost forty million acres, the Northern Pacific also went bankrupt in the depression of 1873, losing control of the St. Paul. The St. Paul then went into receivership (bankruptcy, with an individual called a “receiver” assigned to work out the problems). Over these years, most of the railroad’s bonds, which took preference over stockholders who lost everything in bankruptcy, were bought by Dutch investors.

What Jim envisioned was the opportunity to tie together western Canada and the east, via St. Paul and Winnipeg, if the north-south line could be completed and run well. The Red River Valley could finally be opened to more settlers. Jim believed he could build and run the small railroad, but many obstacles were in his way. The Dutch bondholders were not eager to sell their bonds cheap. The contractor wanted more money, and the receiver and courts responsible for the company were slow to move. Most importantly, Jim did not have enough money to even buy the railroad on the cheap. But Jim Hill was nothing if not patient and persistent.

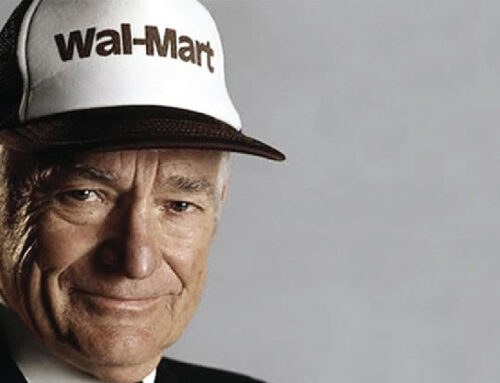

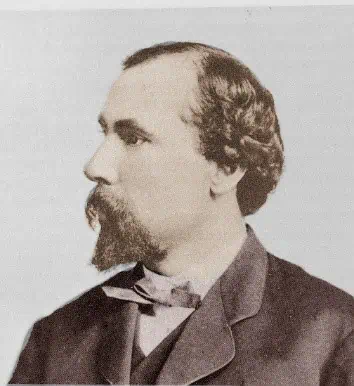

Given the opportunity to help unite Canada, he and steamboat partner Norman Kittson enlisted the support of wealthy Canadians George Stephen and Donald Smith. George Stephen was president of the Bank of Montreal and later named 1st Baron Mount Stephen. Donald Smith, later named 1st Baron Strathcona and Mont Royal, was Stephen’s first cousin. Smith was also at one time president of the Bank of Montreal as well as governor and the principal shareholder of the Hudson’s Bay Company. These powerful Canadians had gotten to know Jim Hill and appreciated his skills and energy. They also shared his vision of opening western Canada via Minnesota.

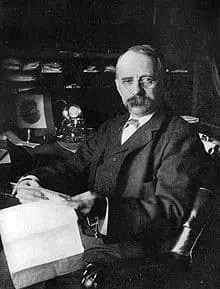

-

Norman Kittson -

George Stephen -

Donald Smith

Thus, Hill, Kittson, Stephen, and Smith, with the backing of the Bank of Montreal, began efforts to acquire and improve the little north-south railroad, the St. Paul and Pacific. The long, arduous process began by reaching out to the Dutch bondholders’ New York representative, railroad financier John P. Kennedy, who soon saw the advantages of Hill’s group taking over the railroad. Through a series of difficult negotiations with the contractors, the receiver, the courts, and the Dutch, the four men eventually achieved control of the railroad for $5.5 million in March of 1878. The cost was recouped by selling off the 2.5 million acres of the land grant, awarded long before Hill and his friends became involved in the railroad.

Nevertheless, more money was required to finish the railroad and to convert it from iron rails to steel rails, as Hill demanded. Despite the wealthy backers, Hill continually struggled to raise more money to get the job done. Over time, Hill succeeded, stretching to the Red River and north to Winnipeg. At the time, none of these men had an ambition to build their railroad further west.

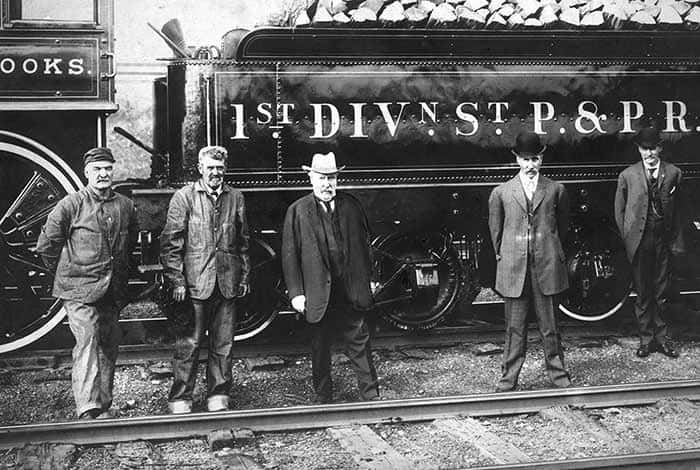

In 1879, these men renamed their St. Paul and Pacific as the St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Manitoba, commonly known as “the Manitoba,” still intending it to be only a regional railroad.

But the owners of the Manitoba did want a line across Canada, from Winnipeg west. They desired a line that they could feed traffic to and from, with their excellent connections south to Chicago and other American points. To that end, Hill, Stephen, and Smith were the driving forces behind the Canadian Pacific Railway in the early 1880s. The Canadian Pacific built west from Winnipeg to the city it created, Vancouver, British Columbia, finally reaching that goal in 1887. Hill convinced top American railroader Cornelius Van Horne to spearhead the project.

Hill believed the most efficient way for traffic to flow to and from western Canada was via his St. Paul and Pacific. Any route from eastern to western Canada that tried to cross the swamps north of the Great Lakes was foolhardy. Nevertheless, under political pressure in Canada, the Canadian Pacific did build that route, reducing the flow of Canadian trade over the St. Paul. Hill felt betrayed by his friend Van Horne but did not blame his friends and partners Stephen and Smith.

Given this new competition for the western Canada trade, the Manitoba began a westward thrust in 1886 from Devil’s Lake in the northeastern corner of the Dakota Territory. Hill also came to believe that small regional railroads like his would ultimately be bought up by the larger lines to secure inbound and outbound traffic. The Manitoba needed to grow to avoid that fate.

Unlike the far more famous transcontinentals, and competing with the heavily government-subsidized Northern Pacific, Hill’s road was built slowly and carefully. Instead of racing across the prairies as fast as possible, Hill methodically built many feeder lines to gather the products of the region, most of them reaching north of the main line into rich agricultural areas.

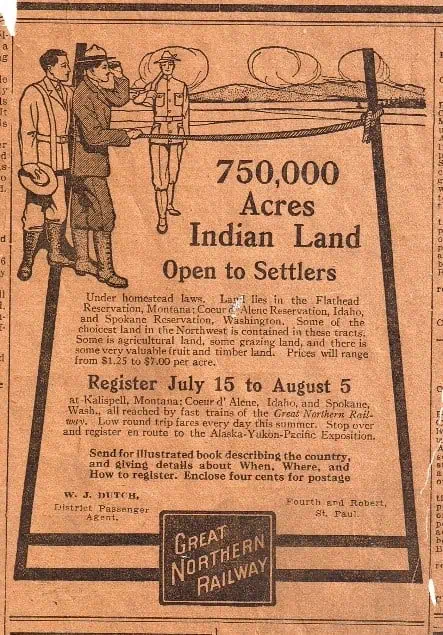

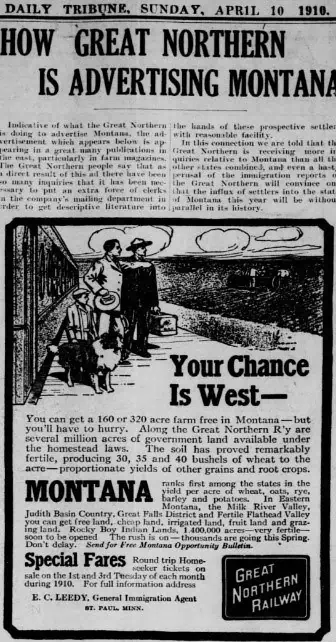

His obsession was to “develop the territory,” to create markets for and sources of freight traffic along the line as it was built. To achieve this, he took great steps to attract and then serve new settlers. Immigrant passenger fares were as low as $5 per seat or $10 for a boxcar holding all of a family’s possessions. In 1882 alone, forty-two thousand settlers arrived in the Red River Valley. Hill set up experimental farms to determine the best soils, seeds, and crop rotation methods. He gave away hundreds of carefully selected cattle from his own model farm. He continually made speeches at every county fair to promote his ideas for better agricultural methods.

In everything he touched, Jim Hill innovated and found better ways of doing things, whether changing from wood to coal fuel, changing from iron to steel rails, or building new terminals for freight and passengers.

Jim Hill was the ultimate hands-on manager. There was no aspect of the railroad business that he did not study and understand. He learned from the older lines in the East. He knew every inch, every hill and curve over which he built his railroad. Hill carefully planned the route, seeking the lowest grades (hills) and least curves, either of which would slow his trains. He checked the rails and equipment, walked the tracks, and wrote thousands of nagging letters to his managers and his investors. When workmen were digging in deep snow to allow trains to proceed, Hill began shoveling himself and had the workers warm up in his private railroad car.

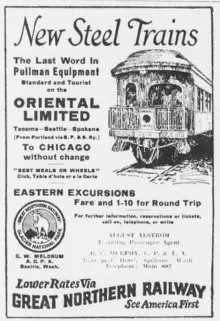

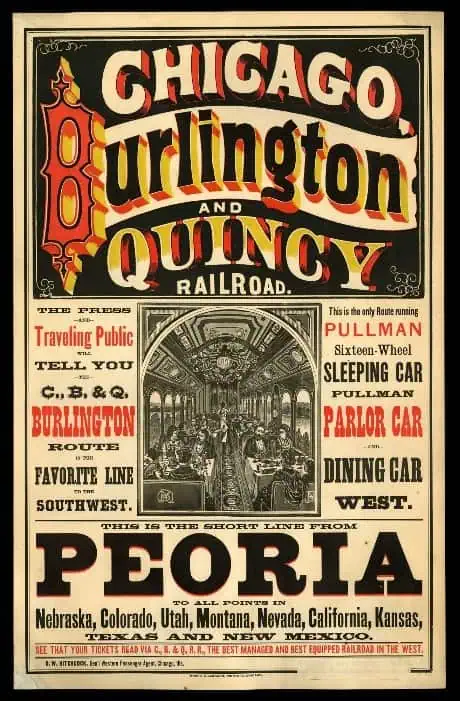

Unlike other railroads which charged high rates to maximize profits, Jim Hill told shippers, “What we want over our low grades is heavy tonnage, and the heavier it is, the lower we can make the rates.” His railroad hauled great quantities of grain and flour out of the northwest toward markets in the south and east, often handing the loads over to the very profitable Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad (“the Burlington”) which connected to Chicago. He hated hauling empties back from loaded trips and dropped rates on returning freight enough to fill his cars. Hill built large steamships to take his freight eastward on the Great Lakes from the port of Duluth.

As he built the railroad, Jim Hill demanded near perfection. He was able to attract talented people who later successfully ran other railroads using his principles, but they rarely stayed long with Hill given his demanding, opinionated leadership. At times, even his friends and investors complained that he worked too hard and tried to do too much. Through his efforts, the railroad became highly profitable, despite offering the lowest freight rates he could achieve.

In 1886, his Manitoba built over 120 miles west to the railhead at Minot, named after Hill’s young second vice president, Henry D. Minot, whom Hill was grooming to play a key leadership role on the railroad. Within five weeks, the town of Minot had a population of one thousand. Henry Minot was the nephew of John Murray Forbes, the Bostonian who controlled the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy. (Henry Minot died in 1890 at age thirty-one when the stopped sleeping car he was sleeping in was rear-ended by another train in Pennsylvania.)

West of Minot lay a vast expanse of less-productive land before reaching the booming Montana mining towns of Butte and Anaconda, followed by two challenging mountain ranges to cross, the Rockies and the Cascades, before reaching the Pacific at Puget Sound. In 1887, Hill built over 640 miles of track from Minot to Helena between April and November, the most track ever built in America in one stretch from the end of the line in one season.

The transcontinental Northern Pacific had been granted almost eleven million acres in the future state of North Dakota, about a quarter of the land area. But by 1888, Hill’s Manitoba railroad had almost 1,000 miles of track in North Dakota, with zero land grants, compared with 814 miles for the Northern Pacific. The next year, the two Dakotas became states. Settlers continued to pour into Hill’s territory. Forty-three percent of North Dakota’s population in the 1890 census was foreign-born, largely from Norway and other Scandinavian countries.

In September of 1889, Hill again renamed his railroad, this time to the Great Northern Railway, a fitting name for an emerging competitor to the Northern Pacific. He adopted a mountain goat as the railroad’s symbol.

Hill placed a high priority on finding the best pass through the Rockies, which had not been a priority for his transcontinental competitors. The fewer curves, hills, and tunnels, the better and more efficient his railroad would be. Indian legend told of a Marias Pass in northern Montana, but no one could find it. Hill hired renowned engineer John F. Stevens, who later planned the Panama Canal, to seek the mysterious pass. With his scout giving up during a blizzard, Stevens finally found the pass on December 11, 1889. The cold was so intense that Stevens walked back and forth all night, not even stopping to build a fire for fear of freezing. The Great Northern thus had one of the lowest and easiest paths through the Rockies.

Hill convinced his friend, Wisconsin timber magnate Frederick Weyerhaeuser, to seek timber in Washington state, resulting in more “heavy tonnage” for the Great Northern. The Weyerhaeuser Company remains the world’s largest private owner of timberlands to this day, controlling or managing over twenty-six million acres in the United States and Canada.

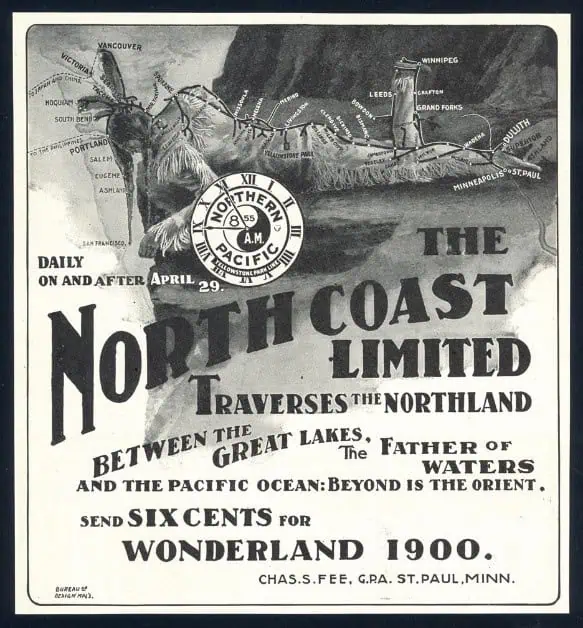

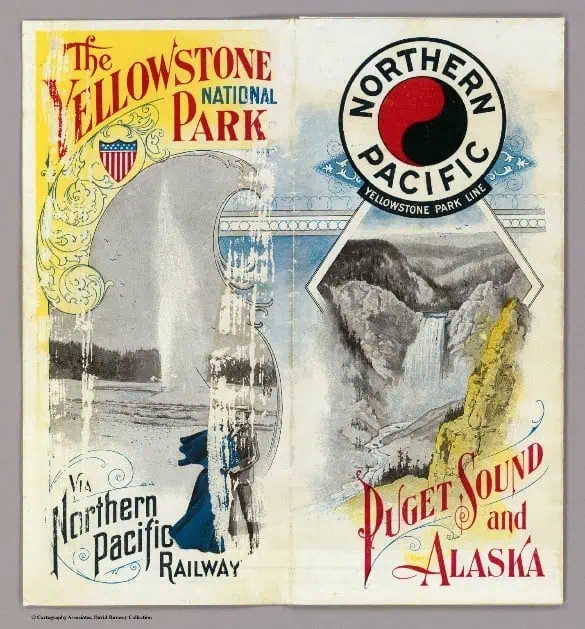

In 1893, the Great Northern finally reached Puget Sound on the West Coast, paralleling the Northern Pacific. Jim Hill began operating freighters from Seattle to Japan and Hong Kong, fulfilling his longtime dream of serving the Oriental trade. The Great Northern was one of the most profitable railroads in America.

But 1893 also brought other opportunities, because in that year the nation was cast into yet another depression.

The Empire Builder

While the well-built and efficiently run Great Northern could still be profitable at even lower freight rates, the poorly built and badly run transcontinentals could not. In 1893, the Northern Pacific, Santa Fe, and Union Pacific all went bankrupt. Their millions of free acres and huge government loans had not saved them from ineptitude.

The same year, Fargo, North Dakota, suffered a massive fire. The city was saved and rebuilt largely through the efforts of Jim Hill, always watching over “his territory.”

In the process of building the Great Northern, Hill had raised more and more money to get the job done. He became an expert in finance as he raised money in England and worked with the most powerful forces on Wall Street, including railroad financiers J. P. Morgan and Jacob Schiff. Jim believed that the bankrupt Northern Pacific, if rebuilt and run right, could also become a profitable railroad. While his efforts to merge the Northern Pacific with the Great Northern were stopped by the federal government, by 1896 he and J. P. Morgan bought enough stock to control the Northern Pacific. They soon had the railroad making money. Hill over time earned the sobriquet “the empire builder” as he remade the entire northwestern quadrant of America.

In 1897, Jim’s sons Louis and James convinced him to purchase a large parcel of cut-over timberland in northern Minnesota for four million dollars, under which lay potential iron deposits. This land in the famous Mesabi Iron range proved fruitful, and to avoid any appearances of a conflict between his own interests and those of his fellow shareholders, Hill sold the land to the Great Northern for his $4 million cost, not making a penny. Over the next several years, the Great Northern and its stockholders (including the Hills) made an estimated $425 million in royalties off these lands. These profits also ensured that principal and interest payments to the Great Northern’s bondholders were also more secure. When later testifying before Congress, Hill’s interrogators had trouble believing he actually made this deal, of which he was very proud. Jim Hill was always aggressive in his defense of the interest of his shareholders and partners. Wall Street financier Jacob Schiff called this dedication to stockholders “a fetish with Hill.”

-

Great Northern Headquarters -

St. Paul Great Northern Station, Minneapolis

The year 1901 proved to be the most ambitious and contentious year of all for the sixty-three-year-old Hill.

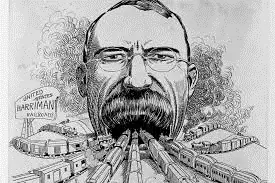

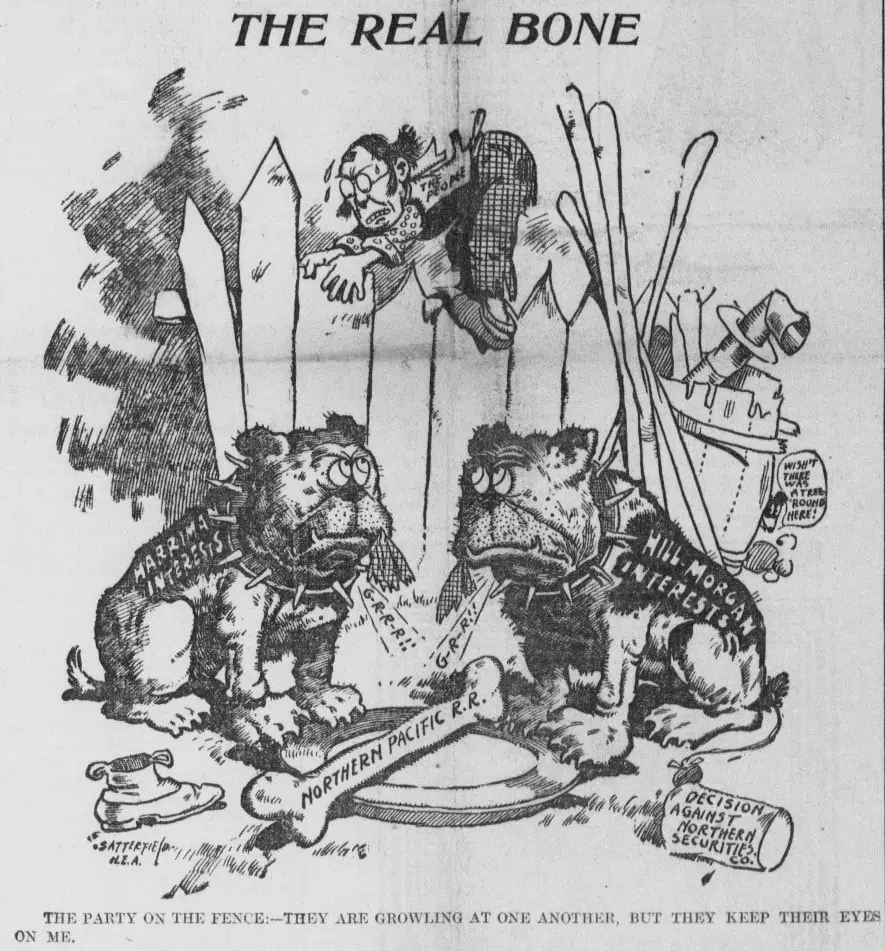

He had long lusted after the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy. The Burlington was one of the most profitable railroads and most reliable dividend-paying companies in America. Its strategic location serving the rich lands from Denver to Chicago, down to Iowa and beyond, and up to Minneapolis and St. Paul made it a tempting target for all the big connecting railroads. Among those was the formerly bankrupt Union Pacific, now rebuilt and effectively run by railroad wizard Edward H. Harriman. Harriman was one of the few who, like Hill, knew how to rebuild and efficiently run a railroad, but he was no friend of competitor Hill’s.

A battle over the Burlington ensued, with Hill and Harriman jockeying for control of the most stock. One group of New Yorkers led by Jacob Schiff and including the Rockefellers backed Harriman; the other led by J. P. Morgan backed Hill. The Burlington’s largest stockholder, Forbes, and its management believed Hill was the better railroader. Morgan and Hill, buying stock on behalf of the Great Northern and the Northern Pacific, won. Jim Hill finally had a line running directly into Chicago, the nation’s most important railroad hub. The Burlington went on to become Hill’s most valuable railroad.

-

Jacob Schiff -

J.P. Morgan -

Edward H. Harriman

Disappointed that he had lost the Burlington, Harriman then tried to gain voting control of the Northern Pacific as a backdoor way to have influence on the Burlington. Some of Hill’s friends had sold their Northern Pacific shares at a profit as the railroad became profitable under Hill’s management. These stock sales, unknown to Hill, meant that his group no longer had voting control of the Northern Pacific. Hill was furious when he discovered the stock sales, and furiously began buying Northern Pacific stock, which Harriman was also doing. The stock’s price shot up. Many traders on Wall Street believed the stock would come back down, and bet against it by “selling short,” which means they would make money if the stock fell. But it kept going up and threatened to bankrupt the many short sellers. Ultimately, Hill and Morgan got back control of the Northern Pacific, bettering Harriman. A Wall Street panic was averted by a last-minute “peace agreement.” Hill and his associates gave Harriman a seat on the board of directors of the Northern Pacific as part of the agreement, but he had no real power over the management of the line.

In an effort to consolidate his three great railroads, the Great Northern, the Northern Pacific, and the Burlington, in 1901 Hill established the Northern Securities Company to hold the stocks of all three. While antitrust laws were rising in importance, the courts had let mergers proceed if there was no proven danger to the public. Given this pattern, Hill and his lawyers thought they were safe to proceed, given his history of lowering rates and serving the territory. But this time, the courts decided that being big was alone enough to stop the deal, and in 1904 the Supreme Court ruled five-to-four that the Northern Securities Company had to be dissolved. This had little impact, as Hill and his friends remained in voting control of all three railroads and insured that they continued to feed traffic to and cooperate with each other.

In 1908, Hill’s railroads gained access to the Gulf of Mexico, via the Burlington’s purchase of the Fort Worth and Denver Railroad and a joint-venture extending through Houston to Galveston. With links to the Pacific, the Great Lakes, and the Gulf of Mexico, the “Hill lines” had become one of the strongest and most profitable transportation systems in America.

The Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central Railroads, powerful older lines that connected Chicago with New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, were concerned that “the empire builder” would now try to acquire eastern roads, building a true coast-to-coast railroad. But Hill reassured them that he had no interest in owning lines in the east. Even today, an invisible line through Chicago, St. Louis, Memphis, and New Orleans, with few exceptions, divides America’s eastern railroads from those of the west.

All was not easy for Hill and his companies. In February of 1910, the most fatal avalanche in US history, a half-mile long by a quarter-mile wide, rolled over a standing train and depot at Wellington, Washington, killing ninety-six Great Northern employees and passengers.

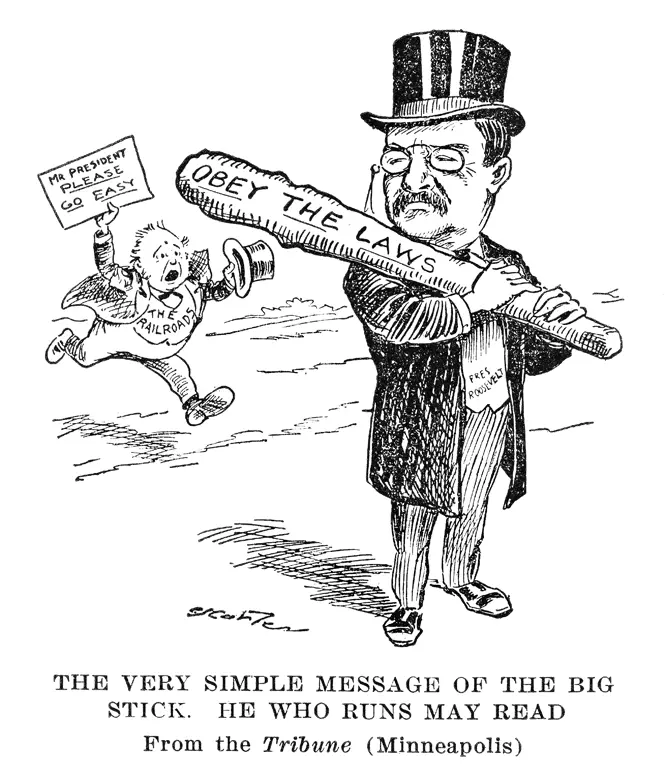

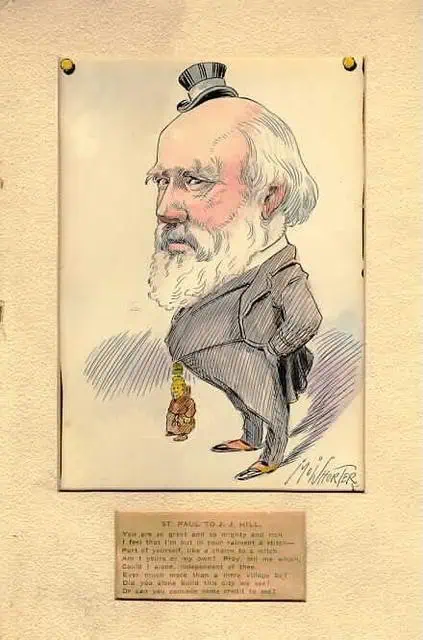

Throughout these years, despite their role in building up America, the big railroads became widely hated. Railroads were the first giant industry in America. Their stocks dominated the stock markets. The Credit Mobilier and other scandals had created major headlines, costing politicians their careers. The railroads had to pick routes which served some communities well but by-passed others. Often the railroad promoters were also backers of selected townsite developments. Shippers and farmers complained about freight rates, and felt they had no control. The railroads were the target of reformers of every stripe, especially Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Taft. In spite of his own efforts to clean up the railroad system and run it in the best interests of his territory, Jim Hill was often lumped in with the other, more rapacious railroad men. One journalist blasted him for taking “eighty million acres in land grants,” when in fact he had taken none.

Begun in 1887, the Interstate Commerce Commission in Washington regulated the railroads. Congress gave it more and more power, ultimately including the authority to approve each freight rate. Months of hearings and the publication of rates a month before they became effective became standard procedure. Jim Hill railed against these developments. When he had been free to compete, he could change his rates daily if needed to meet the competition. In Hill’s view, a month’s notice made effective rate-setting impossible. Hill had offered different rates eastbound and westbound based on the amount of traffic available, but this became harder.

Hill accurately forecast that the heavy hand of regulation would do great harm to the nation’s railroads. By holding rates down, the government did not allow the railroads to make enough money to maintain their tracks and terminals, and to invest to meet the rising traffic levels which Hill foresaw. The fortunes of America’s rail system went into decline. By the 1950s, the industry was a mess, with many lines losing money or making inadequate returns to attract the required capital. A full rebound in the industry did not happen until after President Jimmy Carter and Alfred Kahn deregulated the American transportation industries in the 1970s.

Nevertheless, those in the railroad industry saw James J. Hill as the greatest builder and operator of them all, rivaled only by Harriman (who controlled both the Union Pacific and the giant Southern Pacific, California’s largest landowner). Having made four to five hundred round trips to the East Coast in search of financing and business, he rode different lines to inspect and sometimes get new ideas from each one. Once his reputation was established, even these powerful companies turned to him for advice. The New York Central got new leaders who studied Hill. Alexander Cassatt of the most prestigious Pennsylvania Railroad listened to Hill, who convinced Cassatt to build a Union terminal in Washington, shared with other railroads, rather than going it alone. The Baltimore and Ohio and even lines in Texas took Hill’s advice and thereby improved their performance.

As the twentieth century proceeded, Jim Hill gradually turned over leadership of his railroads to his son Louis, but the “old man” still had the final say.

James Hill the Public Figure and Private Man

Jim Hill was without question the most famous man in his territory, stretching from Minnesota to Portland and Seattle. To the many Scandinavians, he was “Yam Hill.” He was both revered and reviled.

Like others of his era, he could be tough and wily in his dealings. When people at the Minnetonka lakeside resort complained that trains blocked their view of the lake and made noise at night, he moved the railroad two miles away, hurting the resort’s business. But when he found out he had ruined a friend’s boat rental business, he put him back in business at a new location along the relocated railroad line.

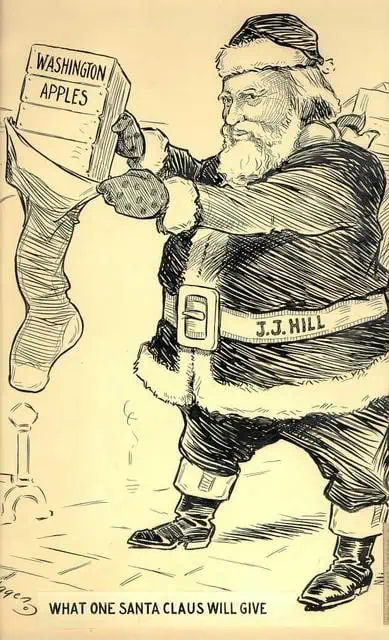

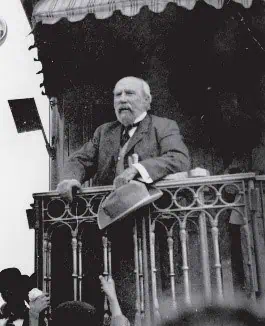

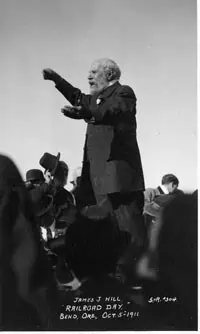

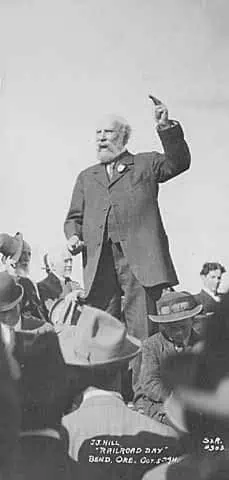

Newspapers filled with cartoons of him, good and bad:

His hundreds of speeches were reprinted, praised or condemned. He wrote articles for national magazines, later combined into his book, Highways of Progress. He always spoke his mind.

Hill was most outspoken about agriculture, about the best soils, seeds, and livestock. He invested his own funds in finding these and then sharing them with the many farmers and ranchers in his territory. A conservationist, he engaged in conferences set up by his foe Teddy Roosevelt, until he found such conferences to be a waste of time, coming to naught. Hill was a man of action.

Hill’s lifelong love of language and literature also seeped into his talks. Despite only having about an eighth-grade formal education, he taught the importance of literature and art. He became a major art collector, especially of the Barbizon School but also buying at least one Renoir.

At the same time, he was a thinker, a visionary. A voracious reader, he loved data and information. He preached free trade and encouraged better relationships with Canada and Asia. His forecast that the United States population would reach 150 million by 1930 shocked people. (It actually took until the mid-1940s to reach that level.)

An extreme workaholic, his loving wife’s efforts to get him to relax and slow down were of no avail.

Hale, hearty, and of massive build, Jim Hill loved to tell stories and jokes and to sing old songs. He seems to have been friends—or competitors—with every important person of America’s Gilded Age. His friends threw big birthday parties for him, attended by such figures as meatpacking king Philip Armour, Chicago merchant Marshall Field, and sleeping car baron George Pullman. His friendships from his earliest days in St. Paul and with his Canadian connections Stephen and Smith lasted as long as they lived, and he wept as they gradually died off. He did not appear to bear grudges, doing business with former enemies when it served his purposes.

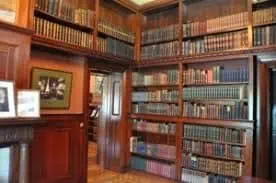

A believer in reading and research, Hill established a reference library in St. Paul, and a few years after his death, his widow, Mary, built a business reference library in his honor, still in operation.

Hill of course became very wealthy and St. Paul’s leading citizen, living in a mansion that is today a historical site.

A billionaire in today’s money, he had a yacht, a home in Manhattan, and one on Jekyll Island, Georgia. He invested in everything from banks to newspapers.

Outside of railroading, above all else he loved his huge family and his annual fishing trips to Quebec with friends.

James J. Hill remained active and outspoken until almost the very end. In 1916, at the age of seventy-seven, he died of hemorrhoids that had become infected. He had been too busy and distracted to have them taken care of earlier.

The Legacy

Many books have been written about Jim Hill, his companies, and what happened to them after his death. His son Louis emerged as a solid successor, greatly aided by railroader Ralph Budd, whom Louis’s father had hand-picked as the son’s business partner.

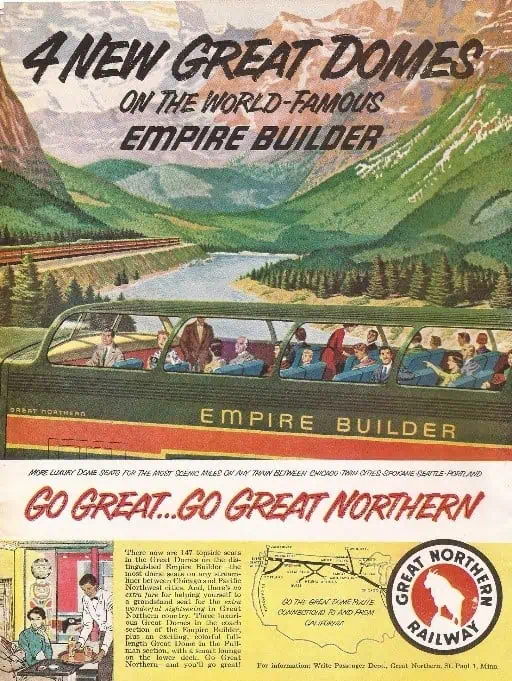

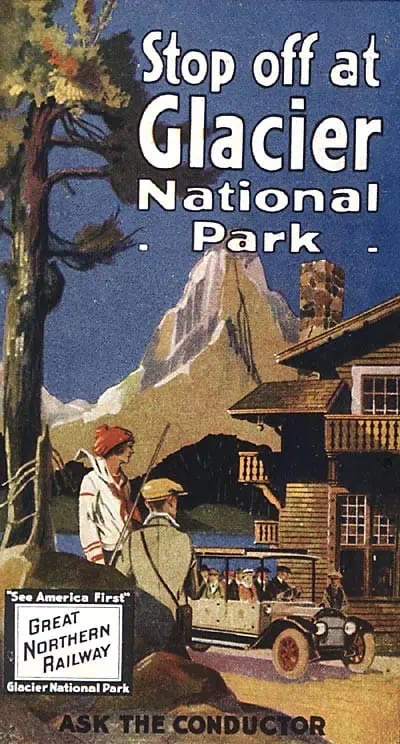

Together, Louis Hill and Ralph Budd continued to build the three railroads. Among their most important achievements was the promotion of Glacier National Park, along the Canadian border in Montana, and the building of sumptuous hotels and lodges in that area. The Great Northern became an important tourist railroad, its most important train named “The Empire Builder.”

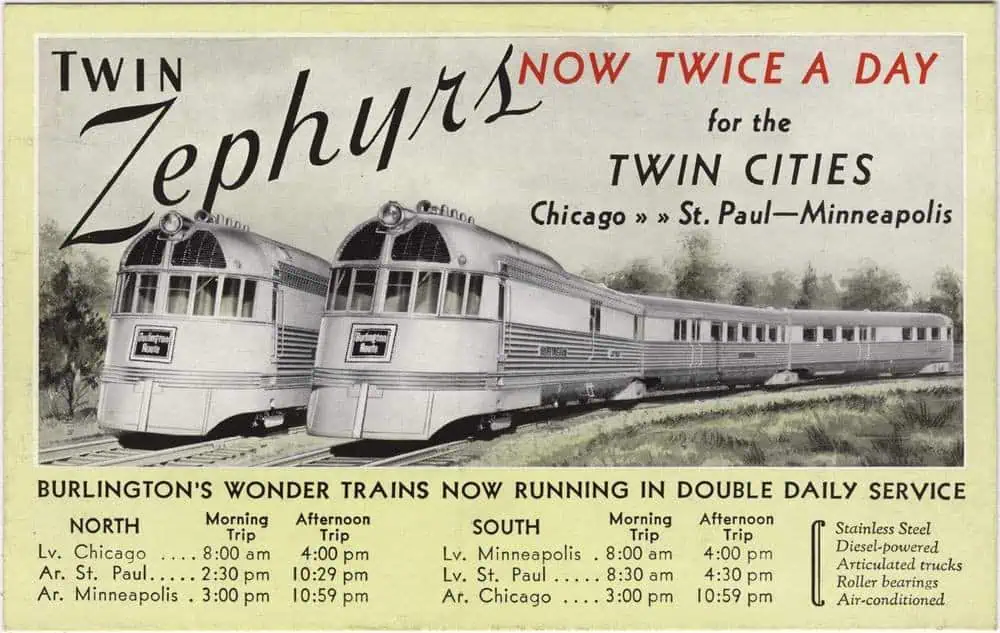

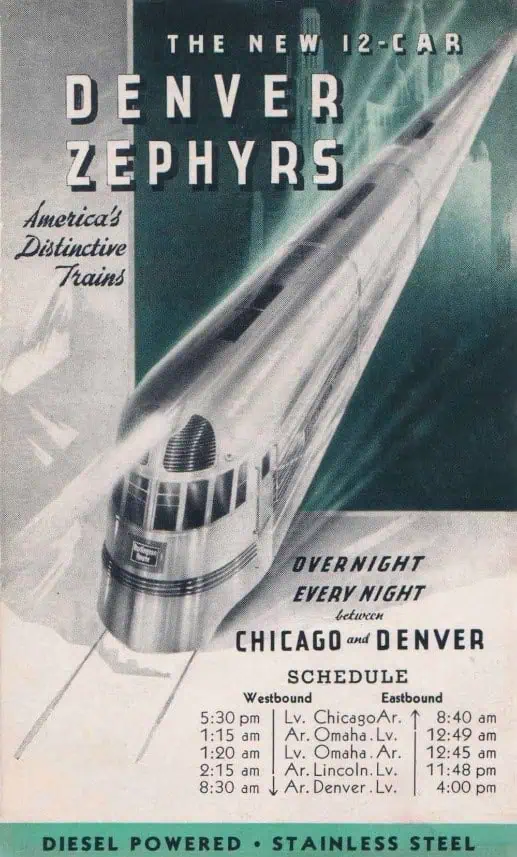

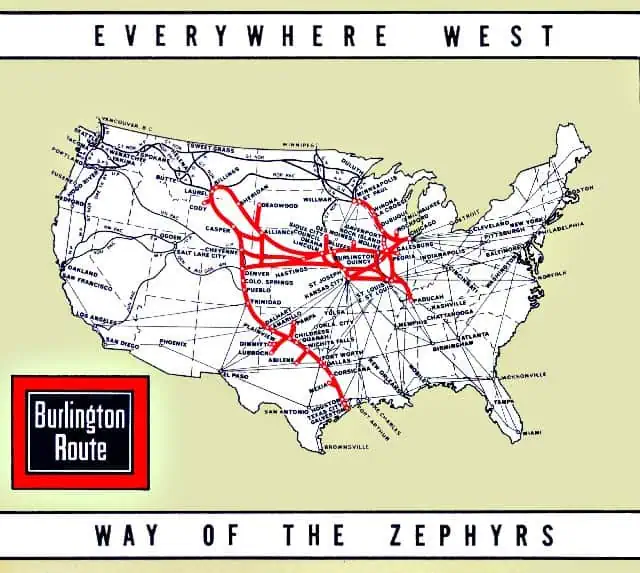

The Burlington under Ralph and his son John Budd was among the first to try diesel locomotives, and was famous for its beautiful streamlined Zephyr trains, one of which can be seen at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry.

Early diesel locomotives of the Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and Burlington:

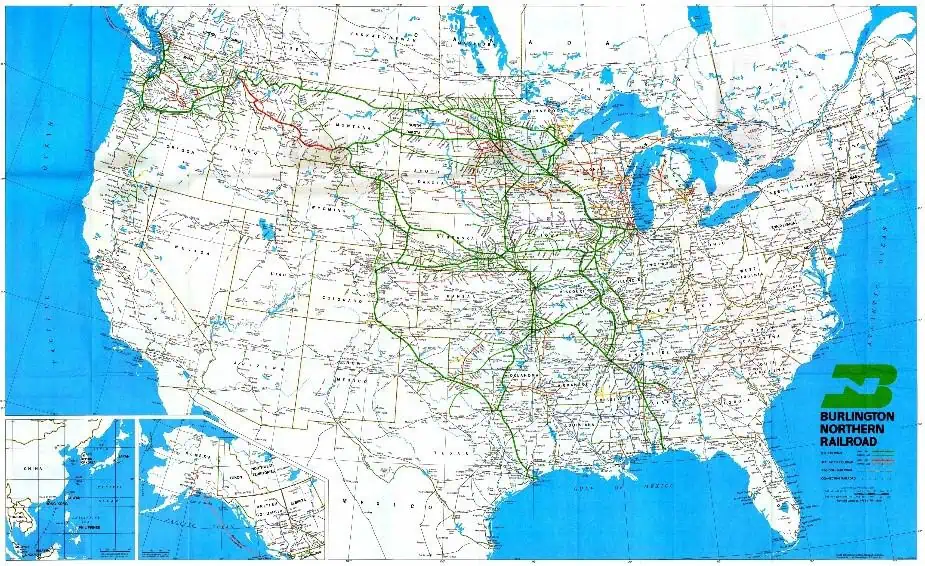

In a twist of fate, in 1970 the Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and Burlington finally were allowed to merge and fulfill Hill’s dream, creating the Burlington Northern Railroad.

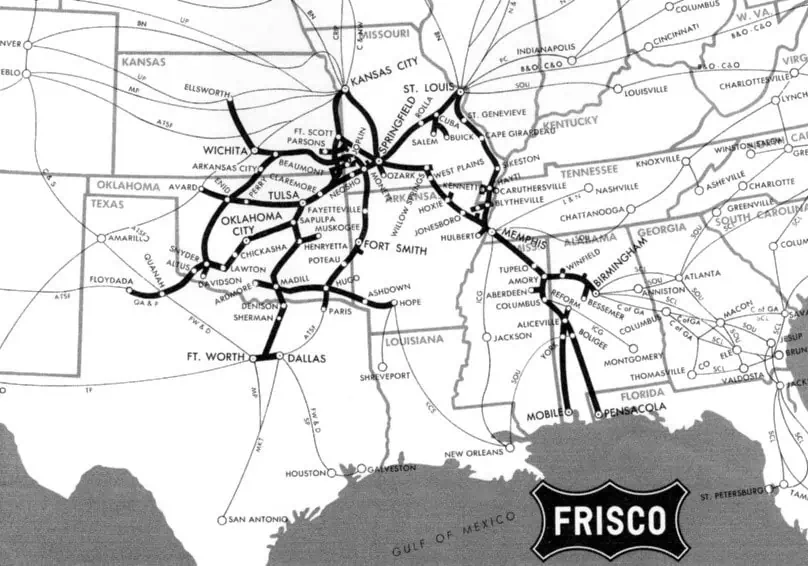

In 1980, the Burlington Northern bought the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad (the “Frisco”), giving it additional access to the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1995, the Burlington Northern acquired the “Santa Fe,” technically the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe, historic route of the famous Super Chief trains between Chicago and Los Angeles. The combined railroad was renamed the BNSF Railway company in 2005. The BNSF was in turn purchased by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Company in 2009. The BNSF is the largest railroad in America, with over 32,000 miles of track in twenty-eight states. It shares the freight business of the western United States with the Union Pacific, which acquired the Southern Pacific in 1998, fulfilling Hill archrival Harriman’s dreams.

Men like Jim Hill opened up America to prosperity and trade. The tracks they laid reshaped the continent, determined where cities would be created, and remain in place and full of “heavy tonnage” to this day, serving all Americans.

Gary Hoover

Sources: Railroad history books could fill several libraries, and because of their importance, James J. Hill and “the Hill lines” have had their share of coverage. The most complete and detailed story of his life, used heavily in writing this biographical article, is the excellent James J. Hill & The Opening of the Northwest by Albro Martin (1976). Michael P. Malone’s James J. Hill: Empire Builder of the Northwest (1996) is shorter and also very good. The definitive, fully illustrated history of the Great Northern is The Great Northern Railway: A History (1988) by renowned business historians Ralph W. Hidy, Muriel Hidy, Roy V. Scott, and Don L. Hofsommer. Charles R. Wood’s The Northern Pacific: Main Street of the Northwest (1968) is one of many books on that railroad. The definitive history of the Burlington is Burlington Route: A History of the Burlington Lines, by Richard C. Overton (1965). The BNSF backed a good book on its history, Leaders Count: The Story of the BNSF Railway, by Lawrence H. Kaufman (2005). There are also many books on the story of the Canadian Pacific and the other roads mentioned in this article. Harriman vs. Hill: Wall Street’s Great Railroad War, by Larry Haeg (2013), delves into those battles. Also helpful in preparing this article were the outstanding The Myth of the Robber Barons: A New Look at the Rise of Big Business in America, by Burton W. Folsom, Jr. (1991 edition) and Chapter XXVI (on Hill) of the Casebook in American Business History, by N.S.B. Gras and Henrietta M. Larson (1939). Hill’s own articles can be found in Highways of Progress (1909, republished 1962).

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.