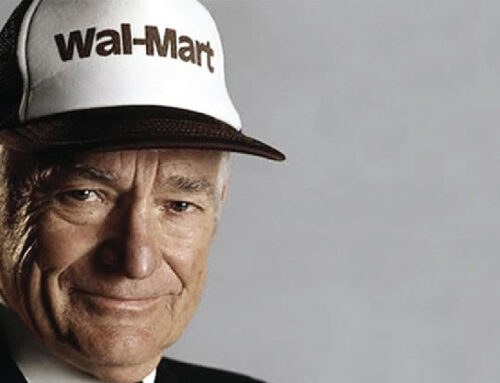

Growing up on a hardscrabble sheep and sugar beet farm in Utah, John Willard “Bill” Marriott sought opportunities beyond his humble Mormon beginnings. In 1927, the twenty-six-year-old Marriott opened an A&W root beer stand in Washington, DC, working around the clock with his wife, Alice. Forty years later, his company was the largest American restaurant company in annual revenue, with a toehold in hotels, which his son then expanded upon. Here is the story of this industry pioneer.

Beginnings

The Marriott family was steeped in the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, whose members are commonly known as the Mormons. According to church history, founder Joseph Smith was first visited by an angel in the 1820s. By the early 1840s, about thirty thousand people had joined the movement, including immigrants from Europe. Believing in polygamy and a story of Jesus that differed from most other Christians, they were continually persecuted being driven from state to state. Smith and his followers established Nauvoo, Illinois, which in the 1840s was about the same size as Chicago, with thirteen thousand people. In June 1844, Smith and his brother were killed when a mob broke into the jail where they were being held. Their friend Dr. Willard Richards survived, hence Bill Marriott’s middle name. Under leader Brigham Young, the Mormons fled to Utah where they established a new community.

Among those making the long trek was Bill Marriott’s grandmother Elizabeth, who had joined the church in her English homeland. In 1853, at the age of twenty-four, she walked the 1,600 miles from St. Louis to Utah barefooted. She became one of the multiple wives of Bill’s grandfather. Bill’s father, Hyrum, was one of thirty children, and Bill was one of 135 grandchildren. After the passing of a federal law banning polygamy in 1882, the Mormons “withdrew their endorsement of plural marriage” in 1890, excommunicating anyone who did not obey the new rule.

Hyrum Marriott was a leader in the Mormon community, along with his plentiful relatives. They created the small farming community of Marriott. Work on the family’s sugar beet and sheep farm was hard and only occasionally prosperous. Bill, born on September 17, 1900, only knew hard work. By the age of thirteen, he was growing his own lettuce and selling it in nearby Ogden, giving his parents the entire proceeds of $2,000 ($60,000 in 2023 money).

Each summer, Hyrum, Bill, and their Basque ranch hands would drive the family’s five hundred head of cattle and several thousand Merino sheep to better-grazing grounds, then in winter as far away as Nevada. Bill Marriott was soon put in charge of these long trips and endless cowboy nights, carrying his Winchester and his Smith and Wesson .38. Life was not easy, but Bill enjoyed the open range. He also remained a devout Mormon, becoming a deacon at the age of twelve. With little time for schooling, Bill educated himself, continually reading everything from Zane Grey’s Westerns to Hawthorne and Mark Twain. He grew to love the writings of Emerson.

The family also took some long trips in the family Buick. Bill soon became the driver, despite laws against someone his age driving a car. He developed a lifelong love of cars and a respect for the freedom that automobiles had brought to rural America.

In 1915, despite his wife’s hesitation, Hyrum let fourteen-year-old Bill take two or three thousand sheep to the Southern Pacific Railroad in Ogden and travel with them to the buyer in San Francisco. That city was the site of the Panama-Pacific Exposition, a World’s Fair. The trip was life-changing for the boy, opening his eyes to a broader world. The next year, Bill took another load of sheep east, to Omaha.

By seventeen, Bill was a priest in the Mormon system and at nineteen, an elder. This was the age at which Mormons were expected to go on their “mission”—generally two years going door-to-door proselytizing their religion, encouraging converts to “their truth.” His father urged him to stay home and help on the farm, but ultimately gave in to the young man’s desire to honor his faith. For the next two years, Bill traveled with another young missionary through Vermont and Connecticut. On one occasion, a mob ran them out of town. Persecution was part of life. All of these experiences were recorded in Bill’s daily diary, a habit he kept up his entire life.

This period also took Bill to New York City, where skyscrapers like the Flatiron and Woolworth buildings amazed him. There he connected with his Utah cousin, Laura Bushnell, whose husband, George, had risen to be the financial vice president of the big J.C. Penney retail chain. Bill rode around town in their chauffeur-driven limousine and spent time in their big Manhattan apartment. He hadn’t realized anyone could afford to live that way.

By 1921, his missionary term finished, Bill headed home by way of Washington, DC. There, he met with Utah’s powerful Senator Reed Smoot, a Mormon apostle (one of the highest levels) who had represented the state since 1903. Thus began Bill’s lifelong involvement in Republican politics.

In Washington, he visited all the important sights, walking around the city in the sweltering humidity. Bill couldn’t help but notice the equally sweaty crowds buying up all the soft drinks and ice cream as fast as the pushcart peddlers could sell it.

When Bill got back to the family farm, he discovered that his father had borrowed $50,000 from the bank to buy more sheep, which were selling at a depressed price. With his dad always hoping to strike it rich, Bill realized that he needed to get away from all this. He wanted to be educated, and he wanted to be more like the Bushnells in New York. With only four dollars in his pocket, he had no money for college, but a former teacher of his took pity on him and let him into junior college. Bill took jobs selling newspaper ads and working in the college bookstore to pay the tuition. At twenty-three, he graduated from junior college.

The Entrepreneur

Since the Marriotts lived in sheep country, Bill knew the owners of the local woolen mills. He and a friend began peddling the long underwear and sweaters they produced, going door-to-door in California. They worked their way into lumberjack country in northern California and southern Oregon. By the end of the 1923 summer, they had sold $12,000 worth of goods, and Bill had $3,000 in his pocket, enough to pay his way into the University of Utah to continue his education.

After a year of college, Bill spent another summer traveling west, selling more woolen clothing. But when he returned to attend another year of college, his father had “better” plans for him: pick up three thousand Merino sheep 250 miles west of the farm and drive them home. Bill felt trapped but decided he had to help his family out. It turned out to be a grueling task, caught in heavy snowfalls, the sheep almost starving as they sought winter feeding grounds. Five hundred sheep were lost along the way.

Bill wanted to finish his final year at the university, but first, he needed money. He joined one of the woolen mills as a sales manager, overseeing forty-five salesmen covering seven states. He made $5,000 and went back to the university. There he met and fell in love with Alice “Allie” Sheets, the daughter of a Mormon bishop who had passed away. Bill finally graduated in the class of 1926 at the age of twenty-six. Meanwhile, he continued in various jobs, working for the woolen mill and teaching theology and English at his old junior college.

Yet one thing stood out in Bill’s observations about business: the A&W root beer stand in Salt Lake City. Only open in the summer, the always-busy stand sold ice-cold root beer in frosty glass mugs, which car hops brought out to your car. He and Allie loved the root beer and stopped there often. Bill’s cousin owned an A&W stand in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and was doing well.

Roy Allen had bought a root beer stand in Lodi, California, in 1919, and in the early 1920s joined with Frank Wright to create A&W. Allen bought out Wright as A&W opened locations in Stockton and Sacramento. He also franchised locations to independent owners in other cities, giving them city-wide rights for $500 to $2,000. The company was a pioneer in franchising as well as “curb service,” recognizing the rising importance of the automobile.

Looking more deeply into the business, Bill discovered that the Salt Lake City stand sold five thousand mugs of root beer a day at a nickel each. The franchisees were making enough money in four months of operation ($7,500 in sales) to take the rest of the year off. Bill knew that A&W’s home turf of central California had hot summers, but he knew a place that was equally sweaty: Washington, DC.

By March 1927, Bill Marriott had secured the A&W rights to Washington, Baltimore, and Richmond. He joined a partnership with his friend Hugh Colton, whose brother was a Utah congressman. Hugh was already in Washington, working for the government and studying law at George Washington University. Bill invested his $1,500 savings plus $1,500 he borrowed from a bank in the business, matching Hugh’s $3,000. The franchise rights cost $1,000; the root beer concentrate bought from A&W cost $2,000, and the rest went for rent, building alterations, furniture and fixtures, and advertising.

Bill and Hugh found an eight-foot frontage for rent on Fourteenth Street, NW, an area with foot traffic from local residents and workers. (Today, Taco Bell and Chick-fil-A are nearby.) They worked around the clock to prepare the site for their stand, squeezing in the required refrigeration equipment. Bill printed up one thousand tickets that said, “This ticket good for one free A&W Root Beer” and had them passed out by high school girls to pedestrians and cars stopped at stoplights.

The “store” opened on May 20, 1927. On the same day, Charles Lindbergh left New York on his history-making solo transatlantic flight. Bill put a radio on the counter so his patrons could keep up with news of the flight, drawing more crowds to the root beer stand. The stand was a success from the outset, but it is doubtful that anyone, except possibly Bill Marriott, expected much to grow out of the tiny business.

Shortly after the opening, Bill flew back to Salt Lake City to marry Allie, then they drove across the country to their new home in Washington, where they rented a tiny apartment. Bill and Hugh worked at their stand from nine in the morning until they closed at midnight, and soon they opened a second A&W stand in Washington. Allie counted the money and kept the books.

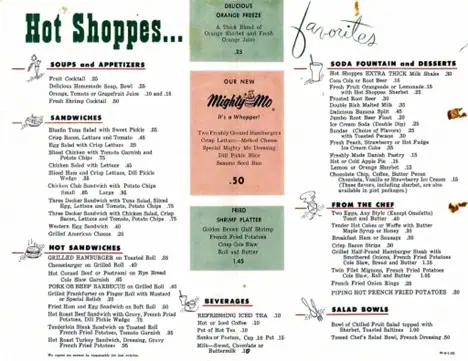

As winter approached, the partners did not want to close down like other root beer stands. Demand for the beverage dropped off as cold weather approached. In Utah, they loved Mexican food: tacos and chili, hot and tasty. They wanted to add those to their stand, but the A&W franchise agreement prohibited the sale of food. So, Bill called Roy Allen and got special permission for his franchise to add food. The chef at the Mexican embassy in Washington generously shared his recipes. He also told them of a food supplier in San Antonio, Texas, since no Washington store carried what they needed. The partners pulled together their nickels and built a small kitchen into their small spaces.

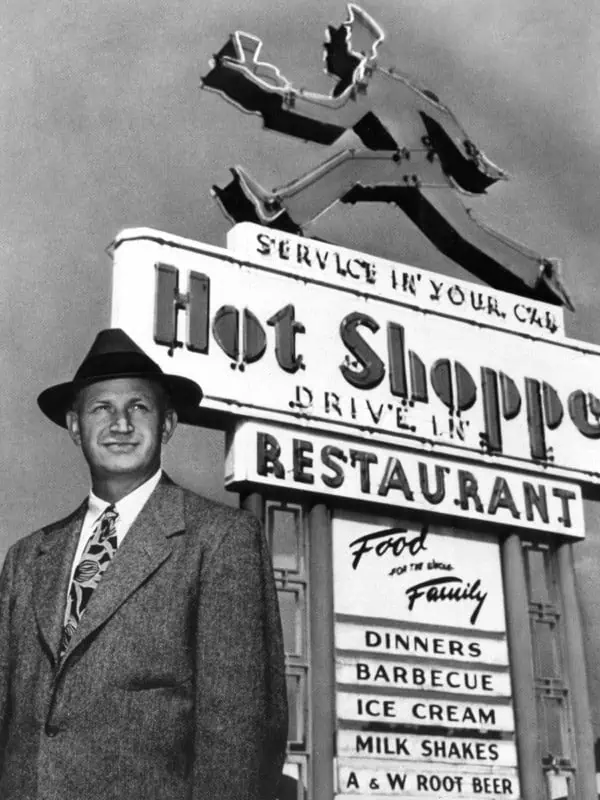

As they were converting the stores, another friend from Salt Lake City dropped by and said, “Hey, Bill, when’re you and Allie going to open this hot shop that I’ve been hearing about?” They liked the idea of naming their place “The Hot Shop,” but thought it too plain so “classed it up” by using “The Hot Shoppe.” In addition to Mexican food, the stores offered “Bar-B-Q” and later hot dogs. More success followed. In the first year in business, their revenues totaled $16,000. Bill was able to draw a salary of $200 a month.

Hugh Colton wanted to focus his energies on applying his law degree, so Bill and Allie bought out his half-interest for $5,000, borrowed from a bank, to become the sole owners of the business. The two soon sought a third location, this time with parking, so they could offer curb service. The new Hot Shoppe used the recently invented folding trays that fit on a car’s rolled-down window. At the time, drive-in restaurants were new with a reputation for “petting” and underage drinking. Bill and Allie had to jump through hoops to get local authorities to allow their new store to open.

The new location, at the corner of Georgia Avenue and Gallatin Street, NW, was an instant success, soon doing $18,000 a month. While it retained a large, revolving A&W root beer barrel on the counter, a chef in a tall white hat carving meat was added. Most items were ten cents, sandwiches fifteen, drinks a nickel. The building was painted orange and black to stand out. This store became the model for future Hot Shoppes.

Through this process, Bill Marriott proved his lifelong commitment to expansion, to growing the business. He also came to realize that he was not really a pure restaurateur; he didn’t cook or have any desire to. What Bill loved was the restaurant business, picking locations and figuring out ways to improve. He soon hired others to stand at corners around the city and count the traffic going in each direction, as well as the number of pedestrians. He accepted the traditional hotel and retail mantra, “location, location, location” as the three keys to success.

Bill also developed a family feeling among his employees, joking with them and getting to know them. He talked to customers all the time. He gradually brought his brothers into the business, making it a true family affair.

In 1929, Marriott opened his fourth store, and his fifth followed in 1930. Number five, at 4340 Connecticut Avenue, was much bigger, likely the largest drive-in restaurant in America, with one hundred carhops.

In the midst of all this, Allie’s widowed mother came from Utah to visit them. There, she met the powerful fellow Mormon Senator Reed Smoot. The two soon fell in love and were married. This led Bill and Allie to engage with the Hoover administration, including dinners at the White House. Both Bill and Allie became more heavily involved in Republican politics.

When Herbert Hoover lost the 1932 election to Franklin Roosevelt, Smoot also lost, ending thirty years in the Senate. Smoot wanted to sell his Washington mansion, but not at Depression prices, so he asked Bill, Allie, and their newborn son J.W. Marriott Junior (“Bill Jr.”) to house-sit until the price rose. Ultimately, the family had enough money to buy the house and stayed there.

Through these events and the rise of their popular eateries, the Marriotts became “movers and shakers” on the Washington scene. They also remained devout Mormons. When Bill became ill and doctors gave him six months to a year to live, he called on church elders to anoint him, and he went on to live another fifty years.

Building a Foodservice Empire

Bill Marriott was joined by his brother, Paul, who opened Hot Shoppes in Baltimore. Bill became a student of the restaurant business, developing new ways to save on costs and innovative methods to analyze each item on the menu. He realized he needed a top food expert and hired the food advisor to New York and Boston’s big forty-store restaurant chain, Schrafft’s, to improve his menus.

At the same time, Bill and the family, now with a daughter and another son as well as Bill Jr., began to vacation with George Bushnell, the J.C. Penney executive, at his lakeside retreat on Lake Winnipesaukee in New Hampshire. Bushnell’s neighbor there was Earl Sams, who had succeeded J.C. Penney as president of the company in 1917. Bill and Earl spent a great deal of time together, and Bill, like Sam Walton, learned the “Golden Rule” ideals of Mr. Penney and his company, including excellent treatment of employees.

In 1937, Marriott’s eighth Hot Shoppe was built on busy highway U.S. 1 on the Virginia side of the Fourteenth Street bridge, on the way to the Hoover airport (which was on land later used for the Pentagon). Bigger and busier than ever, this location became a popular destination to “drive out to” for Washington youth. Bill’s belief in the importance of the automobile continued to pay off.

That year, the company’s revenues were almost $3 million, generated by two thousand employees. Marriott had paid off his debts and developed a lifelong hatred of debt. (His father’s farm had gone bankrupt years before.) Bill and Allie had come a long way from one little root beer stand in just ten years, but they had no desire to stop learning and growing.

Bill noticed that Eastern Airlines flight crews would stop at the new Hot Shoppe and get a meal to go, enroute to their flights at Hoover Airport. Soon passengers were doing the same. All the food served on those early flights was small and of low quality. Marriott started delivering box lunches made at the Hot Shoppe to the airline at planeside. Soon, American Airlines joined Eastern in buying the service, and Bill was providing meals for the twenty-two flights a day in and out of the airport.

By 1941, the company operated fourteen Hot Shoppes in the Washington area, two in Philadelphia, and two in Baltimore. To supply all the stores economically, Bill built a central kitchen—a “commissary,” again leading the industry in innovation.

As World War II came about, Bill observed new government buildings, new defense plants, and thousands of new workers—all of whom needed to be fed. This led him to operate restaurants and cafeterias in industrial and office facilities, maximizing the use of his commissary. The company focused on buying the highest quality ingredients, thus offering far better meals than most office and factory workers were accustomed to.

After the war, Bill announced major expansion plans. The company was far from small—in 1948, they had used ten thousand head of cattle and eighty-five thousand pounds of butter in serving twenty million meals a year. Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower, FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover, and Eleanor Roosevelt were regular customers.

With their increasing wealth, Bill and Allie bought a place on Lake Winnipesaukee in New Hampshire and a 4,500-acre farm in Virginia, which they also used for employee events.

Ever seeking new foodservice opportunities, Marriott built a facility to provide airline meals and added service at airports beyond Washington, serving a dozen airlines. He operated onsite feeding facilities (“institutional foodservice”) at offices and factories in Miami, Atlanta, and Chicago. In 1952, these operations plus his forty-five restaurants in nine states and DC generated $19.7 million in sales.

This rapid growth consumed capital and Bill hated borrowing, so in 1953, Hot Shoppes, Inc., went public and listed on the stock exchange at $10.25 per share, raising $2.5 million for a one-third interest. The Marriott family retained two-thirds of the company stock.

In 1955, Bill announced that he was building a 370-room hotel in Arlington, Virginia, near Washington, the largest and finest “motor hotel” in the world. Amenities would include a Hot Shoppe restaurant, a large swimming pool, air conditioning, soundproof walls, king-size beds, twenty-one-inch televisions in every room, wall-to-wall carpeting, babysitters on call, and a rooftop observation deck.

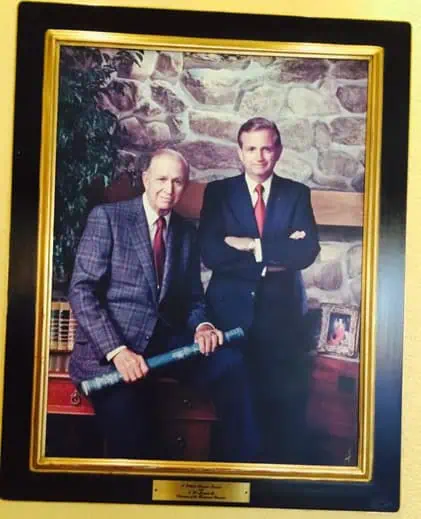

Bill Jr. had graduated from the University of Utah, served as a navy officer, and gotten experience in the Hot Shoppes. In 1958, at twenty-six, he was made vice president in charge of the new hotel division. He quickly made plans to add hotels in Philadelphia and Dallas. The restaurant, airline, and institutional foodservice operations had all grown and now included restaurants along the nation’s emerging toll-road system. Company sales crossed $40 million, almost double the $21 million of five years previously.

By 1968, the company generated over $300 million in sales and was America’s largest restaurant company, edging out Kentucky Fried Chicken, Howard Johnson’s, Dairy Queen, McDonald’s, and their former partner, A&W (in that order).

The family remained politically active, friends of the Eisenhowers and backers of their Mormon friend George Romney for president in 1968. Allie served on the Republican National Committee from 1965 to 1976 and was the honorary chairperson for Richard Nixon’s 1973 inauguration. Their company was one of the largest headquartered in the Washington area, and Bill served on the boards of a major bank and the electric company. They were integral to Washington social life.

In 1964, Bill elevated Bill Jr. to the presidency of the company, then to chief executive officer in 1972. Over time, the company expanded all its operations, becoming the largest airline-feeding company in the world, one of the largest institutional foodservice operators in the nation, and started or acquired other restaurant groups, including Farrell’s Ice Cream, Roy Rogers Roast Beef, and Big Boy Hamburgers (mainly franchised). Marriott even dabbled briefly in cruise ships and in amusement parks entitled “Great America.”

In 1976, with Bill still serving as chairman of the board, sales reached $890 million and net after-tax profits of $30 million, with the family still owning 19% of the company. The 421 owned and 846 franchised restaurants generated 34% of revenues and 32% of profits. The sixty-three flight kitchens at fifty-four airports, 167 institutional foodservice locations, eleven airport terminal restaurants, and eight toll road restaurants produced 31% of both sales and profits. The thirty-five hotels in twenty-nine cities generated 30% of sales and 34% of profits. Bill Marriott and his son had truly created an empire of dining, along with an emerging chain of hotels, though still far smaller than industry leaders Holiday Inns, Hilton, Best Western, and Sheraton.

In the ensuing years, the company took on more debt, often against the wishes of the elder Marriott. But Bill Jr. was bent on expanding the hotel business that he loved as fast as possible.

J.W. Marriott Sr. passed away in 1985, and his beloved wife, Allie, followed him in 2000.

Epilogue

By the late 1980s, Bill Jr. faced increasing competition from larger restaurant organizations, led by McDonald’s. Profitability declined, while the hotel industry offered higher returns on the company’s capital. Under his leadership, the Marriott company sold off or closed its restaurant and other food service operations. Today, airline feeding is dominated by the German airline Lufthansa, and the institutional food service industry is led by the British Compass Group, the French Sodexo, and the American Aramark.

On the other hand, the Marriott company found profits in the managing of hotels, spinning off the real estate but retaining management contracts. The 2016 acquisition of Starwood, owners of the Westin, The W, Sheraton, and other brands, propelled the company to the top of the hotel industry, now significantly larger than Hilton and its other competitors. As of year-end 2022, the Marriott Corporation operated 2,053 hotels with 576,000 rooms and had 6,122 franchised and licensed hotels with 937,000 rooms around the world.

Under father and son, from the most modest of beginnings, has arisen one of America’s greatest and most global companies. With 377,000 employees, the company is also consistently rated as one of the best places to work, the continuation of a tradition started long ago.

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.