Despite being often forgotten today, Henry J. Kaiser was one of the most unusual and diverse entrepreneurs in American history. Quitting school at the age of thirteen, Kaiser started out in the photography business in New York State. But like many others, he was drawn by the lure of the American West. First building roads in Washington State, he soon helped build the western infrastructure, including Hoover Dam and Grand Coulee Dam. He played a key role in America’s victory in World War II by building hundreds of warships at an unprecedented pace. He also created aluminum and steel industries on the West Coast, doing more to bring manufacturing to California than anyone else.

His breadth was impressive as he ventured into housing, Hawaiian resort development, and the automobile industry. His engineers designed huge projects worldwide. Throughout his long life, Kaiser was always full of ideas, looking for a new project, and usually saw the future more clearly than others. His most lasting monument is Kaiser Permanente, the health plan he developed to help his valued workers. Today, Kaiser Permanente has revenues of almost $80 billion. This is Henry Kaiser’s story.

Beginnings

Henry Kaiser was born May 9, 1882, in Sprout Brook in upstate New York, to Frank and Mary Kaiser, both of whom had migrated from Germany in the mid-nineteenth century. Frank Kaiser was a never-prosperous shoemaker and reportedly an alcoholic. The family’s limited income led Henry to drop out of school at thirteen to get a job and help his father, mother, and three older sisters. The country was still recovering from the financial crisis of 1893, so it took three weeks of searching to land a job as a clerk in a Utica Dry Goods store as a stockroom and delivery boy at $1.50 a week. His mother insisted he keep learning, however, and the two read books to each other each evening.

Utica was four miles from the family home: unable to afford trolley fare—Henry walked to and from work each day. Kaiser was a “lively” youth, fun to be around. He demonstrated tricks at parties and was a “natty” dresser. With three sisters, he was comfortable around girls and reports are that they were comfortable around him.

In the next three years, Henry was promoted to sales clerk and then to traveling salesman. He took a correspondence course in salesmanship and learned quickly. But after three years, he was tiring of the dry goods business. When Henry was sixteen or seventeen, he unsuccessfully sought work in New York City. Fortunately, he had another interest: photography. This began when, at age twelve, he acquired his first Kodak Camera (from nearby Rochester). He found work successively at two photography supply companies, traveling New York State selling for them. Kaiser was convinced that photography would be his life’s work.

In 1899, sixteen-year-old Henry’s mother died at the age of fifty-two. Legend has it that she died in his arms, and that he later blamed her death in part on poor healthcare. Since his father was going blind, her death put even more pressure on Henry to support his family. Well informed about the burgeoning photo industry in upstate New York, in 1901 he learned that a part interest in a photo studio in the beautiful, small New York resort town of Lake Placid was for sale. By some accounts, Henry offered to work for no pay for a year, just room and board. But if he tripled the studio’s business in a year, he would get a half-interest. Owner W. W. Brownell accepted Kaiser’s offer.

Henry Kaiser, as he did all his life, worked more hours than anyone else. He sold, he waited on customers, he touched up pictures. At the end of a year, he had earned his half-interest. After another year, he bought out Brownell. The shingle on his studio read, “Henry J. Kaiser: The Man With the Smile.” But he was not satisfied: Lake Placid had a relatively short summer season. Business dried up in the winter. So Henry opened a photo studio in Daytona Beach, Florida, the perfect winter destination. After an initial struggle there, he opened shops in Jacksonville, St. Augustine, and Palm Beach. Traveling between the cities, he often slept on hard train seats, later saying, “I haven’t liked railroads since then.”

Henry stayed at least one slow summer season in Florida. Scratching out a living, he worked as a tour guide on a boat, selling rolls of film to the visitors. Then he developed the film overnight and delivered the finished prints to the visitors’ hotels the next morning.

In 1905, pretty nineteen-year-old Bess Fosburgh, vacationing at Lake Placid, wandered into the twenty-three-year-old Kaiser’s photo studio. Henry soon asked her wealthy father, a Virginia lumberman, for permission to marry Bess. Edgar Fosburgh, leery of the embryonic photography business, said that he would permit no wedding until Henry had saved $1,000, earned at least $125 per month, and built a house for his daughter. He also suggested that Henry go west in pursuit of opportunities. Henry soon sold his photo studios, which continued in business for many years, to his employees and relatives.

In the summer of 1906, Henry Kaiser boarded a westbound train, looking for work in several cities before settling in Spokane, Washington. He marveled at the scenic beauty along the way, falling in love with the West. Henry used his finely-honed sales skills to convince someone to hire him. After being turned away by over one hundred businesses, he decided to focus on the place he most wanted to work: McGowan Brothers Hardware, which sold at both retail and wholesale. Henry proved himself to James McGowan after the store had a fire, leaving much inventory as rubble. Henry hired people to polish the remnants and make them saleable. He joined McGowan Brothers as a clerk at $7 dollars a week. Soon enough, he was promoted to store manager, then put in charge of wholesale sales for Spokane. After several raises, by the spring of 1907, he was on a train back east to marry Bess, having fulfilled his promises to her father. The newlyweds soon moved into a nice, new Spokane home that Henry helped build.

The twenty-six-year-old hardware salesman put in twelve- to fifteen-hour days. Whenever a major new construction project was announced, Henry acted quickly, grabbing the order for the needed hardware, steel, and other supplies. He was earning $250 per month.

On Saturday nights, Bess and the other wives would come down to help close the store, then socialize until the wee hours Sunday morning. Both Henry and Bess were known for their affability. Henry also turned to Bess for business advice, especially about personnel, throughout the years of their marriage. Son Edgar came along in 1908, followed by Henry Jr. in 1917. A baby daughter was lost at birth in the intervening years.

For most men, this would have been a comfortable life. But Henry saw opportunities all around him and was known throughout his life for acting fast. His customers included the leading construction companies of the area, and in 1911 he joined a paving and road contractor, the J. F. Hill Company. He was soon supervising construction projects around the Pacific Northwest. He learned to accurately but aggressively price bids for contracts. By 1913 he was making over $650 per month.

In an internal power struggle at the Hill Company, the emergent victors demanded that Kaiser fake some reports or be fired. He was incensed at the idea. His paychecks stopped coming, but he stayed on the job for four months anyway, to make sure his projects were finished and his customers satisfied. His integrity was impeccable.

Thus in 1914, Henry found himself without a job but with a family to support and a mortgage to pay. Nevertheless, his optimism never flagged.

Building a Construction Empire

Henry Kaiser then bid on a street paving project in Vancouver, British Columbia, besting the experienced competition. But he had no money to buy or rent the required equipment. He went to a Canadian banker and outlined his plans in detail, asking for a $25,000 loan. The banker leaned over his desk, and said, “You mean to sit there and inform me, young man, you want me to loan you $25,000 and you don’t even have a company, you don’t even have any equipment, you don’t have any men? All you have is a contract and an idea that you think might work, and it might make a profit and you want me, on that sort of a basis to loan you this sum of money?” The banker then leaned back and wrote a note on a piece of paper, telling Kaiser to show it to the head cashier of the bank. Henry thought it probably said to kick him out of the building, but instead it said to give him $25,000. Henry Kaiser was at his best as a salesman.

One of his first employees was construction foreman Alonzo Ordway. Ordway said that in their first meeting, Kaiser “applied his vacuum cleaner and learned more about me in the next hour than I knew about myself. . . . I went away amazed and starry-eyed.” Ordway, like many others, stayed with Henry for decades.

Working up to twenty hours a day, Henry got job and after job. His record of bidding low, beating budget, and finishing jobs ahead of schedule became well known. On big contracts, he partnered with other contractors he knew from his years of selling supplies. Some larger older firms provided capital for Kaiser’s projects. Many of these partners became friends for life and worked to help Henry win contracts. His business grew and grew.

Kaiser had always followed opportunity wherever he saw it—from New York to Florida to Spokane to Vancouver—never sitting still. Between 1916 and 1921, he and his family moved to Seattle, then Portland, and then to Oakland, California, which became the seat of his ever-expanding business interests.

During those years, Henry built road after road in the growing Pacific Northwest, including over eighty miles in Washington alone. Model T’s were selling fast and the “good roads movement” captured the attention of politicians everywhere. Known as an incredibly hard worker, Kaiser was also unafraid to jump in on any job. He grabbed a shovel or operated a bulldozer many times—whatever it took to beat deadlines and budgeted costs. Workers appreciated their boss (who developed his long tradition of treating them well), especially when compared to many others in the rough-and-tumble, highly competitive construction business. Once established in Oakland in 1921, Henry took on larger contracts, often in the range of $250,000 to $500,000 each. During the 1920s, his Kaiser Paving Company built over 150 miles of roads in California, including extensive sections of US highways 99 and 40. His focus on doing things fast and well led him to become an innovator, always trying new machines and techniques. He bought the patent rights on one of the first “earth movers” and invented equipment improvements himself. He replaced old-fashioned iron-rimmed wheelbarrows with more expensive ones with rubber tires to ease the effort required to move loads across rocky or muddy ground. Making life easier for his workers meant jobs were finished sooner, accidents were fewer, and workers were more loyal.

The man loved new challenges, new things to figure out. His most famous quote was, “Problems are only opportunities in work clothes.” In 1926, Henry took on his first dam building project, the small Philbrook Dam in Northern California. He continued to work with partners. Large paving company Warren Brothers invited Henry to join them in building a massive road project covering the length of Cuba. In 1927, he took on a subcontract for two hundred miles of road and about five hundred bridges. The almost-$20 million Cuban subcontract was worth more than all the work Kaiser had done since going into business for himself. But when he found bribes were required and suppliers cheated him, he vowed never to work overseas again, a promise he later had to break. His most important partner was likely Warren “Dad” Bechtel, founder of one of the world’s biggest construction and engineering firms. Bechtel was so impressed by the younger Kaiser that he began inviting him to share in big projects. Between 1930 and 1933, Bechtel and Kaiser laid almost one thousand miles of pipeline in contracts totaling about $4 million.

Over these years, Henry built an organization of trusted subordinates. He could not be at every project every day. He valued and rewarded their contributions. Those men found Henry’s work ethic and tireless energy hard to keep up with, but he continually inspired them to do more and do everything better and faster.

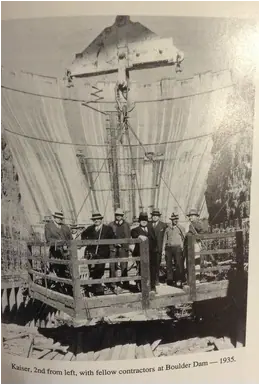

In 1931, Henry Kaiser and Dad Bechtel formed a partnership that joined five other big construction firms to form the “Six Companies” group to bid on the huge Hoover Dam project on the Colorado River. At $48.9 million (over $600 million in today’s money), the Six Companies’ bid was $5 million less than two other groups. This project was a breakthrough for Henry.

As part of a large team of experienced construction companies, he was assigned to be the project’s liaison in the nation’s capital. Thus began a long career of dealing with bureaucrats and politicians. He gradually learned the ins and outs of Washington: who had the power, who to pitch, who to curry favor with. Over his life, these skills earned him big jobs but also substantial criticism from his competitors who were less skilled or less fortunate in their dealings with Washington. He ultimately became the target of congressional investigations when his friends lost elections to the opposite party.

The Hoover Dam project was big news everywhere, one of the largest construction efforts in American history. Between March of 1931, when the contract was officially awarded, and the following December, the crew rose from 106 men to 2,745, eventually reaching 5,251. The enormous site was in the desert south of Las Vegas, where one-hundred-degree temperatures were the norm. With no housing or feeding facilities nearby, the Six Companies had to build Boulder City to hold the men and their families. Working conditions were brutal and dangerous. Enormous amounts of cement and concrete had to be produced and delivered as spillways were cut through the mountain rock. But the nation celebrated when the 726-foot high dam was completed in 1936, defeating flooding and delivering over 2 megawatts of power from the harnessed Colorado River.

Henry Kaiser, Dad Bechtel, and others formed another consortium to win the construction contract for the Bonneville Dam even before they had finished at Hoover. In 1938, another Kaiser-formed group bid $34 million to win the contract to build the massive Grand Coulee Dam (4,173 feet long, creating a lake 151 miles in length). Each project had different challenges. Each was a learning experience for Henry.

While not nationally known to the general public, Henry J. Kaiser had become a major figure in the American heavy construction industry. In 1938, he was a wealthy fifty-six-year-old man. Many men would have slowed down or retired. Not Henry.

Beyond Roads and Dams, Master Shipbuilder

As an expert in every part of the construction process—from politicking and bidding to digging and moving earth—Kaiser saw other opportunities. Henry and his partners had to buy many materials from eastern suppliers, requiring long lead times and high shipping costs. Heavy industry was rare on the West Coast, but the needs were booming. Kaiser had purchased millions of barrels of cement from his suppliers but was not satisfied with the prices he paid. He drew surprised reactions when he bid on a big government cement project without having ever built or operated a cement plant. His first venture outside construction was a cement plant at Permanente near limestone deposits in Santa Clara County, south of San Francisco. Permanente Cement won the $6.9 million contract to provide the cement for the large Shasta Dam project, beating out several established cement companies, which had tried to keep Kaiser out of “their” industry. The first bag of cement came out of the plant on Christmas Day 1939. (Kaiser became well known for ignoring holidays, weekends, and vacations.)

Henry had been a boating enthusiast since his days near the Erie Canal and at Lake Placid. But few could have predicted his next move. As the nation moved toward war, even before Pearl Harbor, he saw the need for more ships for the navy. The big eastern shipbuilders told Washington that they could meet any need the military might have, but they were slow to expand. There were no shipyards on the West Coast. Henry saw an opportunity, but forces aligned against him: the existing shipbuilders and established politicians and military leaders in Washington. He had never built a ship or operated beyond construction and cement. The odds were against him.

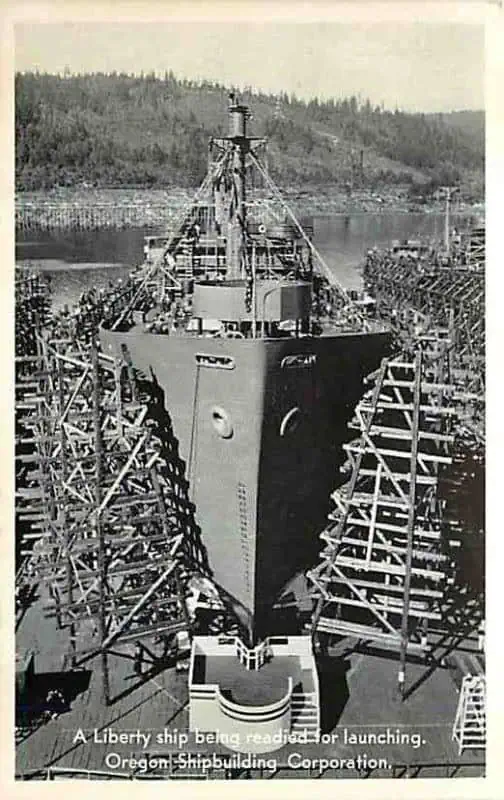

Though the United States had not entered the war, the British had a problem: German submarines were sinking their ships as fast as the Brits could build them. Henry formed a partnership with Todd Shipyards, one of the rare industry participants willing to give Kaiser a chance. In December 1940, the partnership got a British contract to build thirty ships on the West Coast at cost plus $160,000 per ship. The idea was that Kaiser would build the new shipyards at Richmond, California, near Oakland, and Todd would operate them. But Henry soon found Todd unprepared to work as hard and fast as Henry did, and within a year Todd was out and Kaiser was on his own.

Henry soon proved, as he had in construction, that he could work faster, better, and cheaper than anyone thought possible. As the war ramped up, he ramped up. Richmond was completely transformed with the new shipyards, with thousands of workers pouring in from across the country. Housing and schools were built; a credit union for workers was formed.

Finding healthcare inadequate for his workers, leading to too many absences, Kaiser partnered with Dr. Sidney Garfield to create a system of hospitals and affordable services to take care of them. This was the nation’s first big Health Maintenance Organization (HMO). Established doctors and the American Medical Association fought this development at every turn, as it threatened lucrative private practices. Never a fan of government health plans, Henry thought his private approach could help other employers and workers across the nation.

The Richmond shipyard laid its first keel in December 1941. Between then and the end of the war, 747 ships were built there. Moving fast, Henry added shipyards in the Portland area in early 1942, which built another 743 ships. The total cost of these ships was about $4 billion. The most famous of the thirteen types of ships Kaiser built were 821 ten-thousand-ton “Liberty Ship” merchant vessels. Henry urged the yards to compete with each other in speed and efficiency. In November 1942, the Portland yard, under Henry’s son Edgar, built a ship in four days, fifteen hours, and twenty-six minutes. All together, the Kaiser shipyards employed almost two hundred thousand people at the war’s peak.

Sixty-year-old Henry Kaiser was now among the most famous men in America, with the press calling him “The Miracle Man.” Few businessmen had contributed more to America’s victories in the war.

Next Moves, More Opportunities in Old Industries

Henry continued to be frustrated by the lack of manufacturing on the West Coast. Always a student of trends, he came to believe that the US economy would boom after the war. His friends said he had “a preoccupation with the future.” Henry urged American steelmakers to expand their plants, but they and the government experts said they had plenty of capacity to meet post-war needs. After the Depression of the thirties and the war boom, they were more short-sighted in their projections of demand than Kaiser. But Henry turned out to be right.

Not willing to wait for the war to end, Henry moved ahead. In 1941, he opened a magnesium plant at Permanente. Against major industry opposition, he borrowed over $100 million from the federal government to build a steel plant at Fontana, California. Operations there began in December 30, 1942. The Kaiser Steel Company gradually became a moderate-sized steel producer but an important factor in western industrialization. He also created new businesses in gypsum and in sand and gravel.

On April 1, 1946, Henry entered the aluminum business. Industry insiders were sure he would fail, as he had no experience in this industry, which required specialized skills, advanced technologies, expensive factories, and enormous amounts of electrical power. Experts thought April Fool’s Day was the perfect day to begin, before his “assured failure.” When a colleague told Henry that Rome wasn’t built in a day, Kaiser replied, “I don’t know about that; I wasn’t working on that job.” During the first year, his aluminum plant in Mead, Washington, turned out almost 110 million pounds. He went on to open a massive plant at Chalmette, near New Orleans, and to acquire the required bauxite sources in Jamaica. Kaiser Aluminum went on to become America’s third-largest aluminum producer and the most profitable of all the Kaiser companies; in 1966 generating $59 million in profits on revenues of $781 million.

In all these industries, Kaiser’s reputation for taking care of his workers served him well. He generally paid higher wages than his competitors. Henry also became an increasingly familiar face in Washington, gaining the ear of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Unlike most business leaders, Kaiser supported many New Deal initiatives. These moves did not earn him friends in the established business community or among Republican leaders. Corporate executives accused him of being too friendly with the government, the beneficiary of powerful friends in the capital. Some labeled him “the dimpled darling of the New Deal.” While a distraction, none of this slowed Henry down or stopped him from seeking new opportunities.

Henry Kaiser was a master delegator and leader of men. While he trained and developed trusted lieutenants, including his son Edgar, he was always involved in major decisions in every industry and around the globe. He was in continual communication, generating “tons” of telegrams. In 1942 alone, his telephone bill was $250,000. No one was surprised by a phone call from him at 3 a.m. Some believed that he never slept. He would entertain until the wee hours, then be back at his desk before eight the next morning.

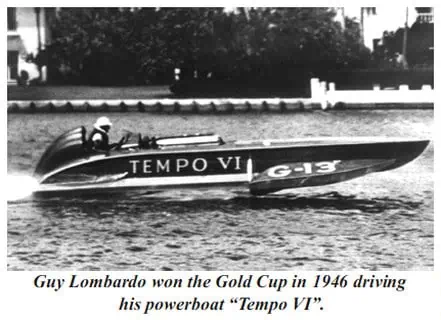

It was said that Kaiser had about twenty new ideas a day, and always had talented associates to evaluate each opportunity. He listened to everyone, but made the final decisions, sometimes overriding his own experts. He had little patience for bureaucracy and long meetings. He did believe in thinking and planning, but where most big companies would do months of study, he’d tell his teams to “get back to me with the answer in three or four days.” Two days later, he was pressing them for their analysis. He was always in motion, as were his key people. One top executive claimed he moved forty times while working for Henry. It appears that the only major hobby Kaiser had was speedboat racing, where he designed and built boats which broke several speed records. Famed bandleader Guy Lombardo was sometimes at the helm.

Not all of Kaiser’s dreams succeeded. He wanted to be “the Henry Ford of housing,” mass-producing ten thousand homes a month, but between 1946 and 1950 Kaiser Community Homes built less than ten thousand homes in total. He considered creating a shipping line to Asia, where he saw great opportunity. Henry was interested in aviation and worked briefly with Howard Hughes on the giant “Spruce Goose” project. He proposed building five thousand cargo planes for the military during the war, to no avail (although one of his companies made some cargo planes for the air force after the war). Another plan to build six thousand airports for small planes across America failed to attract government support. He dabbled in fiberglass and geodesic domes (with Buckminster Fuller). His research and development laboratory in Emeryville, California, tested an “endless stream” of his ideas—including dishwashers, air-conditioners, washers, dryers, lawn mowers, and vacuum cleaners. But Kaiser never achieved the success in consumer-oriented products that he did in heavy industry.

Despite his consumer failures, even his big construction projects worked toward his avowed goal of raising “everybody’s standard of living,” whether it was via cheap hydroelectric power or better housing and healthcare for workers.

His biggest failure was his attempt to enter the auto industry. As in housing, Henry thought he could build a better, cheaper car. He leased the huge former defense plant at Willow Run, Michigan, for five years from the federal government. He partnered with Joseph Frazer, who had led the Willys–Overland Motors company to moderate success. In 1946, the Kaiser-Frazer company launched its first cars, which were well designed and met with some early success. However, post-war inflation prevented them from being as inexpensive as Henry had hoped. Kaiser-Frazer sold stock to the public and it soon hit a high.

As the “Big Three” car makers gradually retooled from war production to consumer needs, and spent heavily on new models, Kaiser-Frazer could not keep up. Henry’s relationship with the slower-moving Frazer ended in 1951. In 1953, the company bought Willys-Overland, the company which produced Jeeps. A major plant was opened in Argentina, with local majority ownership. Plants in Mexico, Japan, Israel, and the Netherlands followed. Despite valiant efforts, including creating the highly regarded Kaiser Darrin sports car and selling the smaller Henry J as the Allstate auto at Sears stores, the company could not achieve enough sales to be profitable. By 1956, Kaiser made only Jeeps, and folded Kaiser-Frazer into a new company, Kaiser Industries, so that the shareholders would not lose everything. (Kaiser Jeep was later sold to American Motors in 1970; the Jeep line continues to be successful today as part of the Fiat Chrysler organization.)

Henry also developed a major engineering operation, Kaiser Engineers, which planned and designed major projects in fifty nations. These projects included the expansion of the Panama Canal, training thousands of engineers and equipment operators in India, a hydroelectric project in Ghana, and one of the world’s largest water development projects in Australia.

By the mid-1960s, Kaiser had three companies: Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical, Kaiser Industries, and Kaiser Steel. Their combined revenues exceeded a billion dollars, which would rank their combined size among the fifty largest American companies, larger than such familiar names as Eastman Kodak and Coca-Cola. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson turned to Kaiser for advice on economic issues. But with the decline of America’s industrial advantages in global markets, most of his empire went into decline in the 1970s and 1980s. Today, Kaiser Aluminum is the only remaining public company, with annual revenues of less than $100 million.

Henry Kaiser Slowing Down? Never!

As the aging Kaiser turned over his companies to son Edgar, one would think he might have slowed down and relaxed. But there is no indication that Henry knew how to do that.

In March 1951, his wife, Bess, died after a long illness. Within a month, the sixty-eight-year-old Kaiser married Bess’s thirty-four-year-old nurse, Alyce “Ale” Chester. This quick marriage sent tongues wagging, but Henry was never held back by convention or by what more conservative people said about him. The new marriage lasted happily until Kaiser’s death sixteen years later.

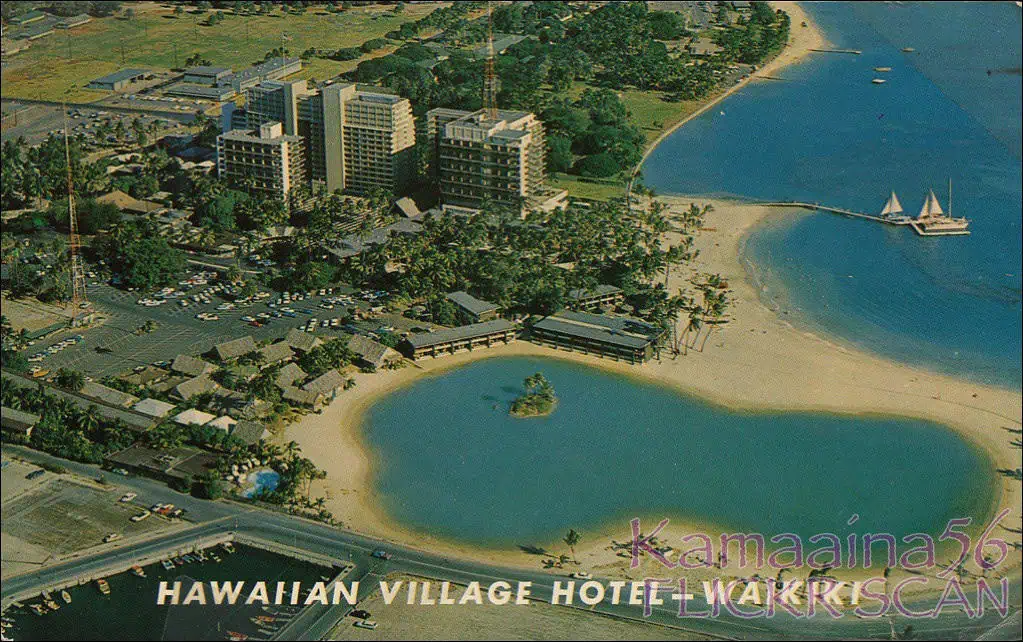

With Ale at his side, Henry took a great interest in Hawaii. He built a large home there and believed that Hawaii had great tourism potential. In 1955, he dug out new lagoons and beaches near Honolulu to create a large resort, Hawaiian Village. In 1959, the new state attracted only 250,000 tourists. Henry thought that number could rise to a million in ten years, but the actual number of 1969 visitors was 1.5 million (and over 4 million twenty years after that). He worked hard to convince the airlines to offer better service and promote Hawaiian tourism. He personally visited American travel agencies with a slide projector in hand to show off Hawaii.

Kaiser spent $7 million backing the #1 television show Maverick with James Garner, where Hawaiian tourism was advertised. While the Hawaiian Village took off slowly and was not profitable for Kaiser, it contributed to the rise of Hawaii as a tourist destination. He later sold it to Hilton and it served as the setting for the Elvis Presley movie Blue Hawaii. Kaiser also tried to develop a six-thousand-acre community in Hawaii, but met with mixed success. He operated television and radio stations there, which not only succeeded but led to more TV stations in Boston, Detroit, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles.

Despite being overweight (up to three hundred pounds) and having multiple heart attacks, Henry Kaiser continued to work twelve-hour days into his eighties. By late 1966, at the age of eighty-four, he was confined to a wheelchair. Yet he told a visitor, “My, aren’t you lucky—you’ve got so many problems!” On August 24, 1967, eighty-five-year-old Henry J. Kaiser died in his sleep.

Few businesspeople in American history have been as diversified in their interests as Henry Kaiser. While others bought out existing companies to create “conglomerates,” he dreamed up and created every business in his empire. Few have matched Kaiser in their passionate visions of the future. Few have done more for their workers. And few are as little-known today.

Over time, his healthcare plan expanded to all his companies, and later opened to the public. Kaiser Permanente became one of the largest healthcare organizations in America. Long separated from the Kaiser companies, in 2018 the giant healthcare consortium generated $79.7 billion in revenues. Henry Kaiser also endowed the Kaiser Family Foundation beginning in 1948, which continues to fund research on healthcare in America today. Despite building so much and helping win the war, Henry’s efforts in healthcare are his most visible remaining legacy.

Source: This short biography is based on the excellent detailed biographical book Henry J. Kaiser: Builder in the Modern American West, by Mark S. Foster, published in 1989.

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.