Today, the Estée Lauder Companies have become among the most important cosmetics companies in the world—against huge odds and well-established competitors. Estée Lauder was a very real person, born to an immigrant hardware store owner and his wife in Queens, New York. Perhaps no other woman has so single-handedly and single-mindedly created such a successful, lasting, billion-dollar enterprise from humble beginnings, overcoming all obstacles. Here is her story.

Beginnings

Josephine Esther (“Esty,” later Estée) Mentzer was born on July 1, 1908, to two immigrant Hungarian Jews, Rose and Max Mentzer. Rose had immigrated to the United States a few years earlier with her five children, following her first husband, Abraham Rosenthal. What became of Abraham is lost in the dust of history, but soon Rose remarried, this time to feed and grain dealer Max Mentzer. Esty was their second child, born at home in Corona, Queens, New York. Corona was a largely Italian community, most noted for being the “ash-heap of New York” in the era of coal-burning furnaces, with barges and truckloads of ashes creating mountains of dust.

Max Mentzer transitioned to owning a hardware store, and Esty gained her first exposure to merchandising, re-arranging the tools and supplies in the store’s front window. She also spent time at the nearby Plafker & Rosenthal department store, operated by the Leppel sisters. Fellow Jews, the Leppels were good merchants, becoming fluent in Italian, extending credit to the community, and serving everyone with respect. Both in the Leppels’ store and in her mother’s treasures from the old country, Esty was exposed to luxury goods and to style.

Uncle John’s Creams

But the little girl soon developed an obsession with beauty. Over and over, she combed her mother’s hair. Esty became attuned to every detail of a woman’s appearance, with a special focus on skin. In 1924, when Esty was sixteen, her uncle, chemist John Schotz, arrived from Hungary with his own facial creams and a few shampoos. Schotz established New Way Laboratories in Brooklyn to make the products. Esty studied everything her uncle created, worked up her own mixtures, and began peddling his mixtures at every opportunity. She said of Uncle John, “Do you know what it means for a young girl to suddenly have someone take their dreams quite seriously? Teach her secrets?” Years later, dermatologists who examined the ingredients of Esty and Uncle John admitted that while the products were not fragrant or elegant, they would have safely done wonders for most people’s skin.

Throughout her long life, Esty was obsessed with showing people how to improve their skin. She would run into strangers in elevators, on the streets—even a Salvation Army lady—and say, “I could make your skin look so much better” as she reached for her ever-present supply of creams. She’d dab a bit here, spread it around, wipe it off, and have the person look in a mirror to see the magic she’d accomplished. The ambitious young woman traveled to Wisconsin to visit relatives, and to Miami Beach, always promoting her uncle’s creams.

“People do make their luck by daring to follow their instincts, taking risks, and embracing every possibility.”

Learning about Love

In 1933, Esty married the handsome, affable Joseph Lauder. They had one son, Leonard, who was to play a key role in the future of Esty and her business. She began going by the name Estée Lauder. She also began what was to become a lifelong “social climb.” Estée knew that women with money were more likely to spend on the finest products, which she believed hers were. She knew they had influence on the opinions of others, and she used every opportunity to meet and hobnob with the elite but always believed her products were good for anyone, no matter their status or budget.

Joseph did not have the drive that Estée did. He’d rather be home with the family than out at society parties. His several business ventures found no success. In 1939, Estée divorced him. For three years, she pursued others, possibly having at least one serious lover. But she found no love there. Joe never gave up on her, never stopped loving her. Estée realized her mistake and her loss, and they remarried in 1942. Soon second son Ronald came along. Their second marriage lasted forty years, until Joe’s death in 1983. They were rarely apart, Joe playing the host to her parties and managing the business and manufacturing side of her future ventures.

Tackling the Market

By 1944, the thirty-six-year old Estée was selling her creams, mixed in their kitchen, in beauty parlors in New York City. Her products worked, customers told their friends, and the tiny business grew. Estée was the dreamer, the inventor, the chemist, the promoter, the salesperson, and above all else the demonstrator. She was tireless.

“Every day I touched fifty faces.” —Estée Lauder

But her customers had to pay cash, as this was the era before widespread use of credit cards, except for charge accounts at the big department stores of the era. Realizing credit would entice more impulse purchases, Estée decided she needed to get her products into those stores, and edged into the famous old high-end New York store Bonwit Teller. But her heart was set on the ultimate New York store, Saks Fifth Avenue. The cosmetics buyer there had no interest, no space, and no budget for the tiny product line. The powerhouses of cosmetics like Helena Rubinstein (one of the richest women in the world) and the arrogant Elizabeth Arden dominated cosmetics in all the big stores.

In 1946, Estée gave away eighty lipsticks at a charity event at the prestigious Waldorf-Astoria hotel. While metal was hard to get in the aftermath of wartime shortages, she made sure the lipsticks were all in attractive metal containers. When the event ended, Saks was mobbed with wealthy customers asking if they could buy Estée’s lipsticks. Saks quickly became and remained one of her most important customers, selling out their initial order in two days. Another important early success was Estée’s presence in the great Dallas-based Neiman-Marcus.

That same year, to the protests of their lawyers and accountants (“It will never work!”), Estée and Joe incorporated the Estée Lauder Companies and devoted all their resources to the venture. The fearful had good reasons—the cosmetics industry is brutally competitive, with companies rushing to copy any success of another company. Great brand names like Rubinstein, Arden, Coty, and others had been around for years. The industry was unregulated, a free-for-all. Women also had the choice of much less expensive products sold by drug stores and later discount stores. The risks were great.

Estée and Joe rented a former restaurant in Manhattan, where they cooked up their beauty recipes on the restaurant’s burners. By the age of fourteen, son Leonard was delivering the product to Saks on his bicycle. This was a true family business, though the Lauders surrounded themselves with well-paid “outside” talent, and they listened to their input.

“Testing a new fragrance … ask you how you like it. The truth is, I won’t pay too much attention to your answer. I’ll watch your eyes.”

Estée’s Methods and Innovations

“For me, teaching about beauty was and is an emotional experience.” —Estée Lauder

But Estée kept demonstrating and selling. Never fond of flying, she traveled America by train. Her son later reported that she was gone for twenty-five straight weeks at one time, while he and his father continued mixing the product. In department store after department store, she was turned away. But she never gave up, calling again and again. She never became angry or fought back, as she did not believe in “burning bridges.” And always—always—she pulled out her creams and other products, and worked on people’s faces. If the cosmetics buyer was a man, she would demonstrate on the back of his hand.

She also began to “work” the editors of the major New York-based fashion magazines. When she got in to see one of the most powerful editors, Carol Snow at Harper’s Bazaar, Snow’s assistants recoiled in horror when Estée touched her face and began working in her creams—no one ever touched the powerful woman! But soon enough Estée had a supporter in the shocked editor.

In the glory days of big department stores worldwide, cosmetics departments were huge traffic draws and often big money-makers. Cosmetics were usually at the front door of the stores, controlling up to half of the first floor, the most valuable “real estate” inside any big store. Cosmetics buyers were powerful people both inside their companies as well as to the multitude of potential suppliers. Many were women, and the most powerful had reigned over their realms for years. They were loyal to their longtime suppliers, and carefully guarded their valuable store real estate, rebuffing the many startups and fly-by-night suppliers. Estée would wait outside their offices all day, day after day if needed, until they finally gave in. Many times, they reacted like the magazine editor when she reached to touch their precious and isolated faces. Estée would go to great lengths, even to smaller cities if a store had a good reputation, once riding six hours in a bus to see a store in Corpus Christi, Texas.

Above all else, Estée Lauder was a learner. Her obsession with beauty led her to a lifelong love of anything beautiful, from Venetian glass to the finest silk fabrics. She had little money for a fancy wardrobe, so she bought few outfits but they were the best she could afford. She was always her best example.

“You could make a thing wonderful by its outward appearance.” —Estée Lauder

Her appreciation of the visual led her to focus on packaging well before her larger competitors. When she decided to improve the color of her jars of cream, she tested colors against every possible wallpaper and background color in her friends’ bathrooms and bedrooms. She chose a light blue that was to serve her well. As success came along, she and her company invested more and more in packaging design and perfection. With enough observation and experience, she relied on her instincts, at times making the lives of her employees and suppliers difficult. Like most great entrepreneurs, Estée Lauder thought no detail of the customer experience was unimportant.

The most important thing in the company’s success was her selection of sales people. Estée would hand-pick only the prettiest and best women to work her counters in the department stores, which she also carefully designed. She would take on no “T&T salesgirls”—always on the telephone or the toilet. Her salespeople had to be ready to demonstrate the products; they had to be educated to evaluate each customer’s skin; they had to be ready to touch everyone who came along. Each had a daily sales goal, as did Estée. At the same time, they should never “oversell.” If Estée saw in her regular sales reports that a salesperson’s average sale was too high, they’d get called on the carpet. No customer should go home and say, “Why did I buy all this stuff that I did not need?” Estée was totally committed to making the lives of her customers better, even if it meant fewer dollars in the short run. She instinctively knew it would pay off in the long run.

A big breakthrough came when she began giving product away. While her facial creams worked wonders, they did not always drive demand. So she’d sell lipstick or a fragrance, and include a small sample of the cream. Thus began “gift with purchase.” The giants of the industry let her know she would never succeed, as she was “giving away everything.” Estée Lauder gift bags began to appear at charity ball after charity ball. Eventually, all of her “wiser” competitors were to adopt the “gift with purchase” pattern.

In all this learning and growth, Estée was ever-present. She never missed the opening of a counter in a new store, from the big cities to smaller towns. She arrived days early to train the salespeople herself; to make sure every detail was just right; to make sure that Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubinstein, or the rising Revlon did not have more space or a better location (to the right as you enter a store). She would talk to every reporter who would listen to her story.

“No one ever became a success without taking chances.”

Taking on the Big Companies

By the 1950s, Estée Lauder had a broad presence in many stores across America, but she was still a tiny player in the industry. Energetic Charles Revson of Revlon fame was the first to use television advertising for fragrances, with great success. Joe and Estée set aside $50,000 to try advertising, a great deal of money for their small business. When they met with ad agencies, they were told that was too small a budget to warrant their time. Frustrated, Estée thought of going to their loyal customers at Saks. Thus began inserts in Saks’ monthly charge card statement mailings, another innovation in the industry. Adding scents to her mailer inserts, her innovation became another big success imitated by her competitors.

Later, when they did have enough money for advertising, they didn’t have the funds for color print ads. So Estée found the finest black and white photographers and created stunning ads, also later copied by her competitors.

Revlon, Faberge, and other larger competitors began to tell Estée they would like to buy her company out, for as much as one million dollars. She would always reply, “Why don’t we buy you out?” They’d laugh in her face, and reconfirm that she would not last long in the rough-and-tumble industry. The head of Faberge, rebuffed in his offer, said to her, “Little girl, you don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Charles Revson was a particularly aggressive competitor, profane and without any of the niceties of the older competitors, copying the moves of Estée and the other companies at every opportunity, building the greatest cosmetic company of its era (outside Avon). Elizabeth Arden so despised him that she could not utter his name, only calling him “that man.” In response, Revson named a fragrance That Man.

Revson had made a big success in nail polish; when Estée’s associates urged her to follow, she asked, “Why tangle with him?” She wanted to wait until her company was bigger and stronger before going head-to-head with Revlon. Later, both the Estée Lauder Companies and Revlon were headquartered in the same building, the General Motors building, nicknamed the “general odors building.” But Charles Revson and Estée Lauder always took different elevators.

Over time, Estée realized that the first day sales of any new product were not a good indicator of how well it would do, as first day sales were driven by all her competitors buying her products and rushing them back to their labs.

Focusing on creams and some lipsticks, Estée was conservative in expanding into unknown turf. But she did notice that women used perfume only sparingly, just for special occasions. It was expensive, and the scent soon wore off. So back she went to the mixing and testing, now with the help of others. By using the right oils, she developed a fragrance that would last for twenty-four hours. Less expensive than the perfumes from Paris, she thought women might use it every day, all day. Introduced in 1953 at $8.50 per bottle, “Youth Dew,” creatively named and packaged, was an immediate hit, soon selling five thousand a week. The company’s annual revenues reached $800,000 in 1957.

In 1958, twenty-four-year-old Leonard Lauder joined the company full-time, after learning management and leadership skills at Wharton, at Columbia University’s Graduate Business School, and in the navy. But long before that, he had been at his mother’s side in her many business dealings. A study of the company’s history demonstrates that this apple fell very near the tree, as Leonard took on a greater and greater role as his mother aged, and took the company to ever-greater heights based on his mother’s principles and beliefs. His younger brother, Ronald, also contributed to the company’s growth, but ultimately left for a life of international work in Washington, art collecting, philanthropy, and Jewish and political activism, unsuccessfully running as a Republican candidate for mayor of New York in 1989 (losing the primary to Rudy Giuliani).

“Business is always there if one looks for it.”

Bigger Ambitions

Gradually, after great thought and debate, often spurred by her sons, Estée expanded the offerings of the company. But when she placed her bets, she took big risks. After introducing Re-Nutriv European style skin cream in the 1960s, she expanded into Aramis for men, and continued to add fragrances. Over time, there were more reports of customers who were allergic to some cosmetic ingredients. Leonard advocated entering the emerging field of “hypoallergenic” cosmetics to serve this market. Estée balked, but finally relented, and in 1968 introduced the “Clinique” line. Clinique did not use the Estée Lauder name, establishing its own presence in department and specialty stores. Saleswomen wore white lab coats designed by Estée, the packaging was different, and the counters lit by clinical fluorescent lighting. Over the next few years, Clinique lost $3 million dollars, a big number for the growing company. But they hung in there, and Clinique went on to be highly successful and profitable.

Estée worked for months to get into the great London store Harrod’s, finally succeeding. But the biggest cosmetics department in the world was in Paris’s great Galeries Lafayette store, where the buyer refused to consider any time spent with the American upstart. That is, until one day, when Estée “accidentally” spilled Youth Dew on the main floor of the store, and customers demanded more of the wonderful fragrance.

By 1968, the Estée Lauder Companies were doing $40 million a year in revenue, still small potatoes compared to the other giants: Revlon generated $314 million that year, and soon enough hit one billion dollars.

Estée was committed to tightly controlling every aspect of the operation. Only family members knew the entire formula for each product, which often had up to twenty-five different ingredients. Estée mixed her own samples, and always tested each to the extreme. She was committed to keeping the company privately owned, avoiding the lucrative temptation of going public. She believed they could never risk the money on new innovations if Wall Street investors were watching their quarterly profit statements. Nevertheless, when she was much older, Leonard took the company public, but to this day the family retains effective voting control of the enterprise.

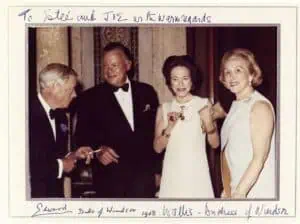

Throughout this period, Estée continued her rise in social circles. She and Joe bought the big old Lehman Mansion in the heart of Manhattan and filled it with the finest objects. They had homes on the ocean in Palm Beach and in the south of France. Estée did whatever it took to spend time with the rich and famous. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor were among the most famous people in the world, so Estée found out when their private railroad car was scheduled to head north from Florida to New York for the summer, and met them at the train station, making sure she was photographed with them. Estée’s autobiography Estée: A Success Story is full of pictures of her with presidents and first ladies, movie stars, and royalty including Princess Grace (nee Kelly) of Monaco. And you know that she touched every one of their faces, making them more beautiful.

In that autobiography, which predictably skips most negatives (never revealing her age), Estée repeatedly admits that she was both “tough” and “aggressive.” Full of philosophies about family, life, relationships, and above all else, business, nothing in her book contradicts what one reads in the gossipy, tell-all “biography” of her, Estée Lauder: Beyond the Magic, by Lee Israel. From all sources, a consistent image emerges: an intensely driven, focused woman who believed in herself and held everyone around her to the highest and most elegant standards.

“Business itself was the purest romance for me.” —Estée Lauder

While her sons and grandchildren went on to become philanthropists and movers and shakers on many projects, Estée’s life was about one thing: making people look better and feel better about themselves. Every battle with her competitors, every fight to get in a department store, and every effort to connect with the leaders of society served one purpose: to demonstrate and sell her superior products.

Husband Joe died at age eighty in 1983; for months afterward, grieving Estée was unable to work, probably for the first time in her life. But eventually she bounced back and continued as the spokesperson for the company until her death in 2004. She was ninety-five years old.

“If you try to impress someone with your power or your wisdom, you will find it hard going. If you are sensitive to his needs, to what will bring him happiness … you will make him your friend.”

The Lessons and Legacy of Estée Lauder

So, what is the upshot of all this, what is her legacy? Son Leonard, now eighty-four years old, is the chairman emeritus of the Estée Lauder Companies. Grandson William is the executive chairman. The entire family still controls a huge block of the voting stock, worth billions—even her granddaughters are worth at least $2 billion each.

The cosmetics industry has changed dramatically. Much larger than it was in Estée’s heyday, corporate consumer product giants Procter & Gamble (Olay, Pantene), Unilever (Pond’s, Noxzema), and Johnson & Johnson (Roc, Neutrogena) are now major players, alongside older firms like L’Oréal of Paris (Ralph Lauren, Lancôme) and Coty (Max Factor, Cover Girl, Clairol). But Estée Lauder is always listed among the five or six largest competitors, depending on how one defines the cosmetics industry. Under Estée’s sons and grandsons, the company had made several acquisitions, including M.A.C. and Aveda. Old lines have sold out: Elizabeth Arden is now owned by Revlon; Helena Rubinstein by L’Oréal.

In fiscal 2017, the Estée Lauder Companies generated revenue of $11.8 billion, still 42 percent through the department stores that Estée first pioneered. Profits were $1.2 billion. Compare that to former industry giant Revlon, with revenues of $2.7 billion and losses exceeding $100 million per year. As of this writing, the market value (“capitalization”) of the Estée Lauder Companies—the amount it would take to buy the company—is $50 billion, a record high. Revlon would cost a “mere” $1 billion to buy; its stock sitting for years at a low.

Each of our stories in the American Originals Series has told of a dreamer who rose up from little or nothing. But Madam Walker’s empire is long gone, JC Penney is in troubled times, and George Eastman’s Kodak is only a shadow of its former self. On the other hand, Walt Disney’s company has exploded in size, now worth over $150 billion. But the Disney company of today is vastly different from the family movie company with one theme park that Walt left behind, and now includes the ABC TV network, ESPN, and is about to acquire much of the Fox Entertainment organization.

On the other hand, Estée Lauder’s passion, dream, and mission continues unabated and in principle unchanged in the Estée Lauder Companies of today, even if far bigger than she could have imagined. One can only stand in awe of the “momentum” that this one “little girl” created, starting from the ash-heap of Corona, Queens.

Sources: Getting one’s head around Estée and her life can be a challenge, as there is no serious or “academic” biography of her. Her own autobiography, Estée: A Success Story, published in 1985, is the best single source, but admittedly biased. On the other hand, Lee Israel’s Estée Lauder: Beyond the Magic, also published in 1985, gives only gossipy glimpses of the woman and her business sense. Harvard business historian Geoffrey Jones’ Beauty Imagined: A History of the Global Beauty Industry is an outstanding history which puts Estée’s accomplishments in a broader context. This history of the company, first written in 2000 for the excellent but expensive International Directory of Company Histories, Volume 30, is a good source of more concrete information on the enterprise. Additional information for this profile was gathered from the financial reports of the companies mentioned, Yahoo finance, and newspaper obituaries.

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.