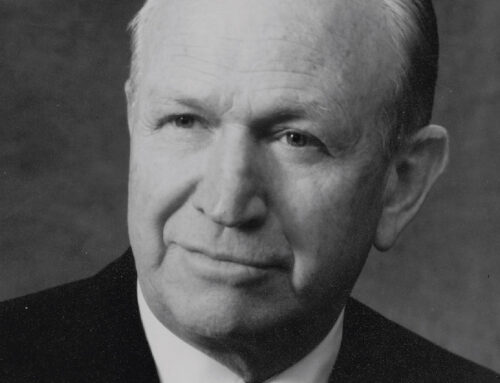

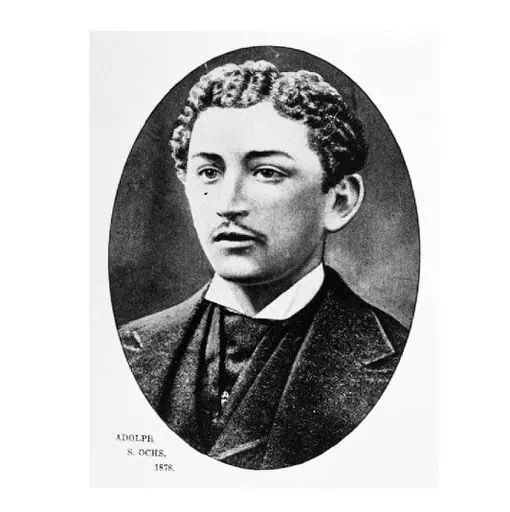

Along with five younger siblings, Adolph Ochs was raised in poverty in Knoxville, Tennessee, by his scholarly but financially unsuccessful father and inspirational mother. In 1869, at the age of eleven, he developed an interest in the newspaper business, delivering papers and then learning to set type. Over time the high school dropout’s ambitions grew. When he came into the business, most newspapers were primarily used to promote political propaganda for one side or the other, serving as outlets for outrage and opinion. Adolph Ochs changed all that, first in Chattanooga, then in New York City. Today his many descendants have absolute control of The New York Times, considered by many to be the greatest American newspaper, one that has led the world in journalistic innovations. Here is his remarkable story.

Beginnings

Adolph Simon Ochs was born March 12, 1858, in Cincinnati to Julius Ochs and Bertha Levy Ochs. Their first child died young; after that, Adolph and his five successive siblings came along. Julius had come from Germany at the age of nineteen, Bertha at sixteen, and they had met in Nashville. Julius was a thoughtful, educated man who spoke six languages and was a leader of the small Jewish community. He had been a drillmaster for the Union Army during the Civil War. But Julius was a repeated failure as a businessman, except for a brief success with a dry goods store in Knoxville right after the war where he and Bertha hoped to help “rebuild” the war-torn city. He bought a big house and the family had servants. But the war had caused merchandise shortages and high prices— soon prices fell and Julius’s inventory had to be sold at a loss.

Buried in debt, the family moved to an unpainted shack. Unlike Julius, Adolph’s mother, Bertha, was a real Southerner— she barely escaped arrest for trying to smuggle medicine to Confederate soldiers in Kentucky, across the river from Cincinnati. Adolph and his siblings thus grew up in an environment where their father debated the moral issues of the day, and in which both sides had to be heard, given their “Yankee” father and “Dixie” mother.

While Julius tried to support his family of eight on his $1–2 per day income as a justice of the peace, in 1869 eleven-year-old Adolph convinced his parents to let him get a job. Adolph became a paper boy for the Knoxville Chronicle, each morning staining his fingers with ink as he folded fifty copies of the paper as they came off the press, then walked four to five miles to deliver them. In a pun on his last name, pronounced “Ox” (and meaning that in German), he soon became known to the other boys as “Muley.” Muley Ochs contributed his $1.50 per week income to the family’s meager funds.

Young Adolph then spent three years trying other pursuits. First, he worked in a drug store, but the aromas did not compare with the pungent odor of printers’ ink. Then he ushered at the Opera House, developing a lifelong taste for the theater. After that, his parents sent him to Rhode Island to learn storekeeping and bookkeeping at the grocery store of a prosperous uncle. Showing his first signs of entrepreneurship, Adolph noticed all the thirsty people at a big political parade in Providence and sold hand-squeezed lemonade and orangeade to the crowd. But Adolph was homesick, and missed the newspaper business, returning to Knoxville at the age of fourteen.

Upon his return to Knoxville, Adolph walked into the office of the Chronicle’s publisher, Captain William Rule, who didn’t recognize the former paper boy (writers and editors worked at night; delivery boys the next morning). Adolph asked him for a job, and the publisher asked what Adolph could do. “Well, I could sweep up some.” Rule found him a broom and hired him at $1.50 a week. Adolph listened to reporters and overheard attempts to sell advertising space. Within a few months, he was promoted to “printer’s devil,” one of those who ran to the telegraph office, picked up beer and sandwiches for the hard-drinking printers, and cleaned the press roller after each run of newspapers. Now known as “Ochsie,” he developed a reputation as a humble hard-worker. People liked him.

Against his parents’ wishes, he quit school soon after he turned fifteen, believing he could learn more working at the paper than going to school. In the same year, he began to learn how to set type by hand. His shift was finished at 11:30 each night, but Ochsie was afraid to walk past the cemetery on the way home. So he hung out with the press and printing foreman until 2 a.m., who then walked Ochsie home. By the age of sixteen, Adolph Ochs was an experienced printer, a valuable skill anywhere in America.

His confidence building, Ochsie dreamed of being a publisher, but one who would print both sides of every story, being fair even to those with whom he disagreed. His idea was a radical departure from the propaganda sheets of the day. His hero was Horace Greeley, the highly regarded and thoughtful publisher of the New York Tribune.

After two years perfecting his printing skills, in 1875 the seventeen-year-old Adolph decided to head west to California, where he could get in on the gold rush and make his fortune, securing a better life for his family. At the same time, he could purchase a newspaper and try his ideas. On his way to California, Adolph decided to get experience on a major paper, Henry Watterson’s Louisville Courier-Journal. His friends and bosses at the Chronicle threw a going-away party for him, and publisher William Rule wrote this in the paper:

Mr. Adolph Ochs, for some years past an attaché of the Chronicle office, leaves on the westbound train today, on a protracted visit to Louisville and other points. Mr. Ochs carries with him the well wishes of all connected with this office, and we would recommend him to all with whom he may come in contact, as a young man well worthy of their confidence and esteem.

At the Louisville Courier-Journal, Adolph was quickly hired, and within a month was promoted to assistant foreman of the composing room. Despite his age, he earned the respect of his workers because he wasn’t arrogant, he listened to them, and he knew how to have a good time, loving to dance and party. His father feared he was becoming too much of a “ladies’ man.” Now known to his colleagues as the more respectable “Dolph,” he asked for exposure to writing and editing— neither of which he was very good at. Nevertheless, the editors sent him to the courtroom to copy information, and his colorless reports were accurate and carefully spelled. When his parents wrote him that his siblings didn’t have the clothes to go to school, he sent home his entire savings of $56.

Homesick, at the age of eighteen he moved back to Knoxville to be with his beloved family. This time, he got a job as a printer at the Knoxville Tribune, and became fast friends with the editor, Colonel John MacGowan. MacGowan encouraged Dolph’s innovative ideas about what a newspaper should be, fair and unbiased. Dolph also befriended the paper’s business manager, Franc Paul, who had started and bought several newspapers around the South, and always had an itch to try it again.

The Newspaper Publisher

Franc Paul’s chance came in April of 1877 when word arrived that the Chattanooga Dispatch was in trouble and for sale. Colonel MacGowan agreed to go in with him on the purchase and management of the paper, but not without bringing young Dolph along. Paul and MacGowan put up the money; Dolph was to earn his share with sweat equity. The three men took the steamboat to Chattanooga, the site of the battle of Chickamauga, now a grim, ruined post-war village. The excited Dolph wrote this letter to his mother on her birthday, listing each of his five younger brothers and sisters:

May God spare you to see Nannie married to a millionaire; George President of the United States; Milton a Senator; Ada a famous author; and Mattie a successful merchant or a large-salaried Rabbi’s wife. As to myself, my prayer is that I may soon be able to make for you all a comfortable home where want is unknown and send my brothers and sisters on their different roads rejoicing.

But such an outcome was not to be—at least not yet. Within months, the Chattanooga Dispatch had floundered, and was deep in debt. Three bosses were two too many. Adolph learned that, in the future, he must be in total control of his destiny—and his newspaper. Dolph let his two partners go their own ways, telling them he would figure out how to pay off the paper’s debts, which he did by soliciting small print jobs for the paper’s dilapidated press.

Nevertheless, Dolph believed in the future of Chattanooga. It was a key center for both river traffic and the expanding railroads, and rumors abounded about iron ore in the nearby mountains. Newcomers poured into town, but only by asking around could they find a mill or blacksmith. Dolph came up with the idea of a city and business directory, and in 1877 the nineteen-year-old published a 126-page directory. His gathering of statistics reported a total of 11,448 residents, only 773 of whom were born in Tennessee—they came from thirty-two states and sixteen foreign countries, plus three who were born at sea. Proceeds from the directory allowed Dolph to eat for a few months, and to send $2–3 a week to his family in Knoxville.

In spite of the failure of the Dispatch, Dolph did not easily give up on his dreams. Word came around that the Chattanooga Times might be for sale. Considered “the only real newspaper in town,” the four-page Times had a daily circulation of 250 copies. It operated from a twenty-by-forty foot shed. Dolph Ochs began to bargain with the owner, who at first demanded $800 in cash for the paper. Relenting, he agreed to sell a half-interest (and operating control) of the paper to Dolph for $250. And he would sell the other half in two years, at a price then set by outside arbitrators based on the paper’s performance. Dolph had no money, but using his rising art of persuasion, talked a local banker into loaning him $300—and personally guaranteeing the loan!

On July 1, 1878, the twenty-year-old Dolph took over full control of the Chattanooga Times, though his father had to sign the papers, because Dolph was not yet twenty-one and could not sign contracts. His more-experienced friend Colonel MacGowan agreed to edit the paper for $1.50 a week, and four broke printers who had been laid off by the failure of the Dispatch signed on. The $300 bank loan was soon exhausted—$250 to buy the paper, $12.50 in legal fees, and $25 to keep the Associated Press from cutting off the indebted paper left only $12.50 in working capital, with the $24 per month room rental soon due.

Dolph worked daily to secure advertising, usually accepting credits for food and clothes from the advertising merchants. With no money to meet payroll, Dolph handed these credits to his staff. When presented with bills, he came up with the trick of saying, “It is our policy to audit all bills before payment; you will have your check tomorrow.” This gave him an extra day to come up with the money. Dolph frantically borrowed money overnight to pay off previous lenders and cover the accounts, often just in the nick of time. His ornate checks, printed on his own press, cleared the bank. Eventually, his creditors trusted him enough to let him pay bills at the end of the month.

Undaunted and proud, Dolph wrote this in the first issue of the Times under his management, July 2, 1878:

It will be the foremost purpose of the manager of this newspaper to make it the indispensable organ of the business, commercial and productive, of Chattanooga, and of the mineral and agricultural districts of Tennessee, North Georgia and Alabama. The paper will contain the latest news by telegraph, markets from all the leading centers of trade, and the freshest news by mail. The local news department shall be as near perfect as hard work and vigilance can make it. In the items of general, commercial and local information, it is proposed to leave nothing to be desired, and no room for home or foreign competition.

Dolph also began to improve the Times: he bought new type, making it easier to read; he redesigned the front page. Circulation and advertising began to grow, but there was soon another setback: yellow fever hit Chattanooga before 1878 came to an end. People thought the fever was caused by “bad hot, humid air.” No one knew until years later that mosquitoes were the source. People stayed away from the town—even steamboats refused to stop. Business dried up and hard times befell the newspaper. Some 366 people died in the city. But throughout the crisis, Dolph insured that the paper was published every day. By the time the cool weather of November had arrived and the epidemic had passed, the Times was $600 in debt.

Dolph Ochs had by now developed a knack for dealing with adversity. When things looked darkest, he often dreamed biggest. And so, instead of pulling back, he plowed ahead. Knowing he could not publish a good paper in the run-down facilities, he moved the Times to larger, two-room quarters. As the paper improved, Dolph borrowed again and again.

As he turned twenty-one, Dolph moved his family from Knoxville to Chattanooga, and even hired his father as the treasurer of the Times, a job he did well. Thus began a long history of hiring his own relatives.

In 1880, the time came for Dolph to buy out the other half-interest in the paper. The required outside arbitrators valued that half at $5,500, twenty-two times what it had been worth only two years earlier. Dolph scrambled to borrow the money and regretted not buying the whole company for $800 two years before. Never again would he leave the pricing of a deal so open-ended. Nevertheless, his indebtedness was now in the thousands, not hundreds, of dollars and he worried about it constantly.

By 1882, the twenty-four-year-old Dolph was free of debt and was running one of the best newspapers in the region. He installed his family in a big brick house in a good neighborhood of Chattanooga. Dolph became the leading booster of commerce in Chattanooga, and entertained visitors from around the nation. He was even briefly the president of the Chattanooga Medicine Company, later known for Gold Bond Powder, renamed the Chattem Company, and acquired by French pharmaceutical powerhouse Sanofi for $1.9 billion cash in 2010.

In 1882, he also met Iphigene “Effie” Wise of Cincinnati, daughter of Rabbi Isaac Wise, considered the founder of Reform Judaism and also the founder of the Hebrew Union College. In 1883, Dolph and Effie were married, and celebrated by going to Washington for their honeymoon, where they were treated to tea with President Chester Arthur. Effie began writing book reviews for the Times. Every evening, Dolph brought her flowers or a small gift before returning to the office to keep working.

Adolph Ochs, twenty-five years old, was now financially comfortable, had made a home for his large family, and was respected by editors and political figures throughout the South and beyond. He befriended President Grover Cleveland when the president visited Chattanooga. Dolph had every reason to sit back and rest on his laurels. But that would not have satisfied him.

Chattanooga was now booming. Iron ore was nearby. A group of citizens, including Dolph, agreed to buy 20,000 acres for a large development for $103,000. But the seller would not sell to the group, only an individual, so Dolph signed for the whole $103,000. Hopes died down when higher quality ore was found near Birmingham, and the development stalled. Although his partners in the deal had agreed to the land purchase, only Dolph’s name was on the contract, so he sold off all his investments except the Times to pay off the debt. He was broke again. In this same period, he and Effie’s first child died at birth, and in 1888, his father, Julius, died at the age of sixty and was buried with full Union Army honors.

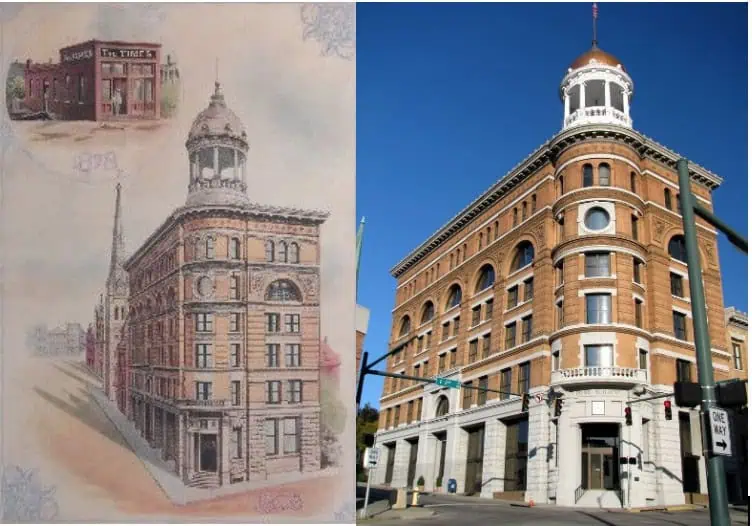

How did Adolph Ochs react to such challenges? He decided to build a big new building for the Times in the heart of Chattanooga, six stories of granite, topped by a gold dome, filled with brand new presses. As the construction bills piled up, Dolph sunk deeper and deeper into debt. He borrowed more money to pay even the interest on the money he had already borrowed. Around the clock, he worried that he would have to declare bankruptcy, costing him his most precious asset—his reputation.

Throughout his life, Dolph went to great lengths to appear prosperous. He carried with him letters of recommendation from his prior colleagues and dressed well, even if he stayed in cheap hotels to save every penny. Only Effie knew what bad shape he was in. And in 1892, their only surviving child, Iphigene, arrived—named after her mother. The same year, the new Chattanooga Times building, known today as the “Dome Building,” opened for business. Dolph had made his mark on the city, despite his financial woes.

The Big Deal in the Big Apple

Dolph Ochs could only see one way out of his predicament: buy a bigger newspaper and make it even more profitable than the Chattanooga Times. While continuing to borrow money and manage the Times, he spent the next few years looking for a candidate. Ever-confident in the future, he set his sights on New York City, where he was barely known and would be considered a country bumpkin. He negotiated to buy the struggling New York Mercury, but when the owners required any buyer to continue their political editorials, he backed out of the deal. Dolph was never willing to yield control or abandon his dedication to being fair to all sides. He was a “Conservative Democrat” and his opinions were expressed on the editorial page, but never bled over into the news pages or the front page.

Then, in March 1896, just as he turned thirty-eight, Dolph received a telegram, informing him that The New York Times might be purchased for a reasonable price. Founded in 1851, this Times had once been considered one of the city’s leading newspapers under editors and owners Henry Raymond and George Jones. But after Jones died in 1891, the paper was sold to the editor and other employees in 1893 and fell on hard times under weak business management.

The New York Times had reached a daily circulation of at least 40,000 in its glory days. But by 1896, that figure was down to 9,000, ranking thirteenth among New York newspapers. Joseph Pulitzer’s flashy and ever-innovative Evening World was number one at 400,000, followed closely by William Randolph Hearst’s Morning Journal at 300,000 and the Morning World at 200,000. While Pulitzer and Hearst engaged in sensational “yellow journalism”—so named after the Yellow Kid comic that both papers carried—more serious papers included the Herald, Sun, and Tribune. The Times wasn’t profitable—it was losing over $100,000 a year. The New York newspaper field was crowded with ambitious men. Some, like Pulitzer and Hearst, had very deep pockets to fund their ideas and hire large numbers of reporters.

Adolph Ochs had nothing but indebtedness and his dream of publishing a great newspaper. In The New York Times, he saw a tarnished name that he thought he could revive, rising up to equal or exceed its past glories, a belief shared by few if any others.

The country was engaged in a political battle over gold-backed currency (“sound money”) and the looser free silver standard championed by William Jennings Bryan. The New York Times and the New York financiers, along with Adolph Ochs, believed in sound money. Several powerful New York financiers, including J. P. Morgan, had invested in The Times in the hopes of keeping it and the case for sound money alive. These men had tried to entice some of New York’s top newspapermen to run the paper, but all turned them down, thinking the task hopeless.

With a par value of $1 million worth of stocks and bonds outstanding, The Times seemed far out of Adolph’s reach. Then word came that some of the large stockholders would be willing to sell for one-fourth of that; even $250,000 would have seemed an impossible dream to some, but not to Adolph.

Adolph began his campaign by meeting with the editor-in-chief and part-owner of The Times, Charles R. Miller, at Miller’s home. Miller knew little of the Tennessean, and planned a short and unimportant meeting before heading off to the theater with his wife and children. A few minutes after Adolph started his pitch, Miller told his family to go ahead without him, that he would join them later. He never made it to the theater. By the time, after midnight, that the two had finished their conversation, Miller was convinced that Dolph could in fact revitalize The Times.

With one key figure on his side, Dolph began a furious campaign to convince the other stockholders and bondholders, with Miller’s support in hand and armed with letters of recommendation from across America, including one from President Grover Cleveland. In one typical day, he held eighteen meetings between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m., plus fifteen minutes for lunch. He met with Charles R. Flint, the founder of several “trusts,” including the U.S. Rubber Company. Flint, the largest single stockholder in The Times, also founded the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company, soon to be renamed International Business Machines (IBM). J. P. Morgan was convinced after just fifteen minutes of hearing Ochs’s ideas. Gradually, the key investors came to believe that Adolph Ochs was the man to save their newspaper and their investment.

These investors then offered Dolph the chance to run the Times—with an outrageous salary of $50,000 per year ($1.5 million in today’s money). Dolph turned them down—he was only interested in full control. Through a series of financial restructurings and negotiations, in the end, Dolph came up with $75,000 of his own money (likely borrowed), and the right to take over voting control of the paper once it had made money for three years in a row.

Remaking The New York Times

Turning the Chattanooga Times over to his brother George, Dolph Ochs became publisher of The New York Times on August 18, 1896. His statement in the paper included these words:

It will be my earnest aim that The New York Times give the news, all the news, in concise and attractive form, in language that is parliamentary in good society, and give it as early, if not earlier, than it can be learned through any other reliable medium; to give the news impartially, without fear or favor, regardless of any party, sect or interest involved; to make the columns of The New York Times a forum for the consideration of all questions of public importance, and to that end to invite intelligent discussion from all shades of opinion.

ADOLPH S. OCHS, New-York, Aug. 18, 1896

This statement, so unusual for the era, was reprinted with accolades in newspapers across the country.

Dolph spent morning, noon, and night learning every aspect of the paper. He got to know every employee. His office door was open to all and he preferred nudging to giving orders. Addressing every employee as “Mr.,” the thirty-eight-year-old was soon known as Mr. Ochs to all but his family and closest longstanding friends.

“Mr. Ochs” moved gradually but sure-footedly: he upgraded the type, the paper, and the ink, all to make the paper easier on the eyes. Just nine days after taking over, a newspaper trade magazine wrote, “A glance at The New York Times since it has been in the hands of Adolph S. Ochs is like a gleam of sunlight on a cloudy day. The professional sees the handiwork of a fellow artist. With the reputation of printing on the worst presses in the city, The New York Times now appears a typographical beauty.”

Adolph began to make editorial changes, as well. He had his financial editor expand the business section, though other editors scoffed that such content was dull, rapidly becoming the most complete record of the city’s commercial life, read daily by hundreds of businessmen. Financial advertising doubled, then tripled, then quadrupled.

Encouraged by the book-loving Effie, Ochs added a Saturday book review supplement, which in turn brought book ads from the major publishers.

While other papers had Sunday magazine sections, they were filled with cheap fiction and poor illustrations. Adolph replaced these with the best halftones money could buy and his Sunday magazine covered current affairs, the arts, and theater intelligently.

Schoolteachers and ministers began to use the paper in their lessons. The big New York department stores, which had long ago abandoned The Times, began to seek advertising space.

As circulation began to climb, Adolph adopted the slogan “All the News That’s Fit to Print,” which is still used by the paper today.

The city’s political bosses came to him with a proposal that they place his share of the city’s advertising for bids in the paper, paying The Times $30,000 a year. While the financial results were improving at The Times, it was still losing money and could have used that $30,000. But when he discovered that the city spent $200,000 advertising in every city paper when the law only required posting in one paper, he not only turned the city down but also editorialized against the needless handouts of taxpayer money, sticking to his high ethics despite the financial loss, and angering nearby City Hall.

Circulation rose to 25,000 by 1898, but that was still not enough to draw sufficient advertising to make it profitable. In that same year, the World and the Journal used their yellow journalism methods to cover and promote the Spanish-American War. In a gamble, Adolph lowered the price of The Times from the three cents charged by the other “serious” papers to the one cent price of the World and Journal. His competitors thought that would cheapen the paper, but it worked, and the price remained in effect for twenty years. In 1899, circulation rose to 76,000. In August of 1900, after circulation had reached 82,000, the paper had been profitable for three years, and Adolph Ochs was given stock certificates representing 50.1% of the shares, guaranteeing him absolute control. The forty-two-year-old moved his extended family to New York, but always referred to Chattanooga as “home.”

Bigger and Better

In 1902, with circulation exceeding 100,000, Adolph decided that he needed to build a new, monumental headquarters, as he had done in Chattanooga. The major New York newspapers had been based on Newspaper Row, facing City Hall in lower Manhattan. As population and commerce moved northward up the island, Adolph decided to move with them. Failing to find an appropriate site near 23rd and Broadway, he chose a triangular parcel of land where 42nd street crosses Broadway, then considered too far north. On that parcel, he built the Times Tower, the second tallest building in the city and the world at twenty-five stories and 363 feet. Around the base, he created running lights that posted the day’s news. And the city changed the name of the old Longacre Square to Times Square. In 1905, at a phenomenal cost of $2.5 million, the new tower opened. In 1907, Adolph came up with the idea of the New Years’ ball drop from the top of the building, which still continues each year.

By 1912, the paper had outgrown even this building, and built the “Times Annex” two hundred feet west on 43rd street to hold the massive printing presses. This newer building was again doubled in size in the early 1920s.

Meanwhile, the paper continued to make news of its own. With the retirement of managing editor Miller, in 1904, Adolph selected Carr Van Anda of the New York Sun to replace him. Van Anda was a near-genius, even later correcting one of Albert Einstein’s formulas. He was also an aggressive newspaperman. During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5, Van Anda with Adolph’s blessing shared the expense of an onsite steamer with the London Times, then regarded as the top paper in the world. During the battle for Port Arthur, The Times posted the first newspaper story ever received from a ship at sea, scooping all competitors. In 1907, The Times led the industry with the first direct transmissions from Europe using the new Marconi wireless technology.

When aviation emerged, the World in 1908 offered a $10,000 prize to the first person to fly from Albany to New York City in a single day. Chartering a train to track the flight, Ochs and Van Anda reported the successful flight before even the sponsoring World. Nearly twenty years later, The Times helped finance Charles Lindbergh’s historic solo transatlantic flight, receiving in return first rights to the story. The Times also sponsored Admiral Peary’s exploration of the North Pole. While these ventures represented large financial risks, they contributed to the reputation (and readership and advertising) of The Times.

As the Titanic was sinking in April 1912, the shipping company did not at first admit how dire the situation was. But Van Anda foresaw the worst, and The Times was the first paper to report on the tragedy. When the survivors reached New York, The Times had dozens of reporters ready at dockside to capture their stories, printed more completely than in any other newspaper.

By 1916, after twenty years of Ochs’s management, The Times circulation had reached 344,000 copies each day. Advertising was at record levels. With reporters now spread around the world, The Times led in coverage of World War I.

But even this prosperous era was not without challenges. Adolph lost his beloved mother, Bertha, in 1908. Ever the Southerner, she was buried with a Confederate flag draped over her casket. His newspaper was continually harangued by those who objected to its objectivity. When World War I broke out, he published the entire text of statements by the British and German governments, leading to claims that he was either a British puppet or loyal to his German heritage. When he published letters from readers criticizing the paper or its opinions, others railed against him. Some competing papers even claimed he was just a figurehead working for J. P. Morgan and other wealthy Wall Streeters, which had no basis in fact. But Adolph held true to his principles, seldom wavering.

In 1925, after twenty-five years of Adolph’s management, it was reported that The Times company had earned a total profit of $100 million since “Mr. Ochs” took control. All but the $3 million paid out to stockholders had gone back into making the newspaper the best in the world. Adolph Ochs’s newspaper was now considered the most important and influential newspaper in America, and perhaps the world, read by leaders and thinkers across the globe. Despite all the challenges and obstacles in his way, Adolph had achieved his dreams.

The Later Years

As Adolph Ochs aged into his fifties and sixties, he enjoyed his newfound prestige and wealth. He traveled widely, including annual tours of Europe. He had four grandchildren and dozens of grand-nephews and grand-nieces from his five siblings and took many of them with him on trips. In the United States, he often chartered private railroad cars. As he traveled, he dined with kings, presidents, and shahs. He danced and drank.

Ochs loved his huge family and provided most of them with jobs at his two newspapers. He and Effie threw parties and showered the children with gifts.

Living for years in a big house in Manhattan, he later acquired a vast estate in White Plains, up the Hudson River north of the city, as well as a large summer home at Lake George, New York. As the years went by, he visited the offices of The Times less often, though he always kept an eye on his trusted lieutenants and the paper’s policies.

While visiting his “hometown” of Chattanooga and meeting with lifelong friends there on April 8, 1935, the seventy-seven-year-old Ochs keeled over at lunch and died. Over 3,000 people paid their respects at Manhattan’s Temple Emanu-El. Afterwards, a seventy-car procession proceeded to the beautiful marble mausoleum he had built for the family in Westchester County, New York, where he was laid to rest with the rabbi’s words, “A good name is better than precious oil.” Adolph had penned his own epitaph: “None knew thee but to love thee, None named thee but to praise.”

A Complex Man

Like most of the others we have profiled in the American Originals series, Adolph Ochs was a complex and sometimes contradictory man.

He refused to hire women reporters and opposed suffrage for women, to the consternation of his wife and daughter. Yet he left controlling interest in The Times to an enduring trust controlled by his son-in-law Arthur Hays Sulzberger, his nephew and key Times executive Julius Adler, and his daughter Iphigene. When debate arose as to whether Arthur or Julius would replace her father as publisher, Iphigene had the tie-breaking vote and chose her husband. Despite his disappointment, Julius worked alongside Arthur Sulzberger for the next twenty years.

Ochs was proud to be Jewish, and in fact believed he would not have been as successful had he not been part of that oft-abused minority. Yet he refused to let The Times become too much of a voice for Jewish causes and opposed Zionism and the creation of a Jewish state in the Middle East, as did many other powerful New York Jewish leaders.

Always viewed as humble and self-deprecating by his colleagues and friends, he nevertheless constantly wrote letters to his wife and mother crowing about his accomplishments.

Ochs was a perpetual optimist, and full of self-confidence in the most worrisome of situations. At the same time, increasingly as he aged, he had long periods of exhaustion and depression, his doctors sending him off for respites. The loss of loved ones struck him deeply, and the rise of Hitler even more so.

He was generous with his large extended family, hiring them, taking them on trips, and leaving them money in his will. Yet they consistently complained that he treated them like children, and always had the final say in every family decision.

Adolph Ochs was above all else a human being. But he was a man with a dream, a vision of better journalism that he would never abandon or betray. He overcame all obstacles to turn his dream into a reality, one that lives on today.

His Legacy: The New York Times Today

As the twentieth century proceeded, The New York Times crossed 700,000 in daily circulation and over 1.4 million on Sundays. With the rise of digital media, which has shaken the American newspaper industry, by 2017 The Times was down to 540,000 weekdays and 1,066,000 on Sundays, still remarkable numbers. Including digital-only subscriptions and 173,000 subscribers of international editions, total paid subscriptions totaled 3.6 million that year. In 2017, The New York Times Company posted revenue of $1.675 billion and pre-tax income from continuing operations of $111 million. The Times appears to be navigating a changing world with reasonable success. In 2007, the company moved to yet another beautiful new skyscraper, continuing an Ochs tradition. The company also operates a state-of-the-art printing plant in Queens, New York, which would have made Adolph proud.

While some might question whether the paper has stayed true to keeping editorial ideas out of news reports, The Times remains one of the most read and respected newspapers in the world. It has won more Pulitzer Prizes than any other paper and stands alongside the Wall Street Journal as the most important and influential American daily newspaper.

Adolph Ochs’s dream of keeping the paper in the family has also come true. Due to the trust he set up (revised by his successors), his descendants control over 90% of the Class B stock, which selects nine of the company’s fourteen directors, thus giving them total control. Those trusts are set up to continue at least another hundred years. The family also controlled the Chattanooga Times until it was sold in 1999. On January 1, 2018, Adolph Ochs’s great-great-grandson Arthur Gregg “A. G.” Sulzberger, age thirty seven, became the publisher of The New York Times.

______________________________________________________________________________

Sources:

This story is largely based on the biography of Ochs written by former Times reporter Doris Faber in 1963: Printer’s Devil to Publisher: Adolph Ochs of The New York Times. While written for young readers, we found the facts intact and the story well-told. For a complete history of the family and the company, with more details, The Trust: The Private and Powerful Family behind The New York Times by Susan Tifft and Alex Jones (1999) is excellent. There are many other books about The Times and the newspaper industry, including the critical role of Adolph Ochs and The Times in changing American journalism.

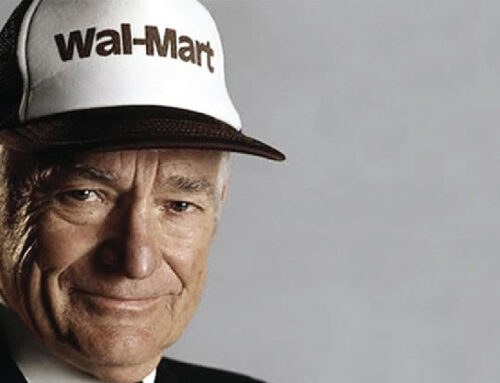

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.